A sideways look at economics

People say that there’s a grain of truth in every joke. If you watch enough stand-up comedy, you can find interesting economic observations too. In a performance from the 2000s, Chris Rock distinguishes between the rich and the wealthy. He says that Shaquille O’Neal, the NBA superstar, is rich; the team owner, who pays his multi-million-dollar salary, is wealthy. He goes on to list reasons why that distinction matters. Wealth, he points out, creates more wealth. It’s passed from one generation to the next. Meanwhile, being rich is temporary. It can be lost with “one crazy summer and a drug habit”.

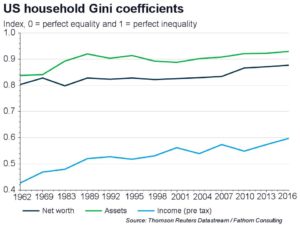

Debates over income and wealth inequality existed long before he recorded that segment. Such discussions have returned once more in 2017, following President Trump’s proposals to cut taxes for America’s richest. When economists discuss inequality they use the so-called Gini coefficient to measure it. This was devised by Corrado Gini in 1912. It ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 equivalent to perfect equality and 1 perfect inequality. It has traditionally been used to assess the distribution of incomes within countries. Since 1962, the US Gini coefficient has increased from 0.43 to 0.60. Once the effect of taxes and government transfers are included, this figure falls to around 0.4. Most left-wing politicians tend to focus on taxing the rich, in order to increase the share of national income that’s redistributed to reduce the post-tax Gini by more.

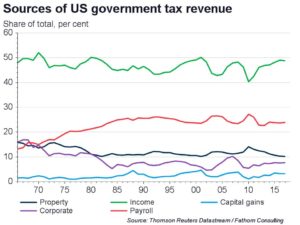

While the distribution of wealth (as highlighted by the green line above) is much more unequal than that of income, few politicians have proposed policies to source greater government revenue from assets, at least outside of Caracas. The US household wealth Gini, for example, was 0.93 in 2016, having increased from 0.84 in 1962. Despite that, wealth is lightly taxed when compared to income. Indeed, taxes on labour income generate the vast majority of government revenue. In the US, around half of all taxes come from income with an additional 24 percentage points generated from payroll. Taxes on capital gains contribute just 3 percentage points, while levies on property, an important source of household wealth, add another 10 percentage points, around the same as corporation taxes. Warren Buffett has lamented this, pointing out that he pays a lower effective tax rate than his secretary. The same might be true of the owner of the LA Lakers and Shaquille O’Neal.

I can already hear arguments against the increased taxation of wealth. After all, isn’t wealth simply the accumulation of saved income, all of which was already taxed? Many think it would be unfair for the authorities to double-dip. In any case, wouldn’t attempts to reduce income inequality bring down wealth inequality too? Not necessarily.

There are many channels through which higher wealth can generate higher future incomes at an accelerated rate. The most immediately obvious channel would be that higher wealth enables individuals to invest in assets which generate additional income return. Hence wealth can create future income, which in turn becomes future wealth. Additionally, some assets, which appreciate in value, can earn capital return rather than income return. Examples of these are not hard to find — art, fine wine and trophy property all fall into this category. One could even argue that bitcoin should be included within this group. At present, individuals’ capital gains tax only generates 3% of US government revenue.

Some studies also find that increased household wealth helps to determine future incomes via its effect on educational outcomes. Moreover, redistributionist income tax policies prevent the accumulation of wealth, as millennials forced to choose between buying avocado on toast, and saving for a deposit on a flat or their pension, can attest. These are dilemmas that those from wealthier backgrounds may not have to confront. Of course, intergenerational wealth transfers are taxed to some extent through various inheritance/estate taxes. However, these often prove controversial and typically contribute little to the state’s coffers — for instance in France inheritance tax generates just 1% of total government revenue.

Irrespective of fairness, there are other problems with wealth taxes. A primary one is that they’re easier to avoid. Through some clever financial engineering, a wealth tax introduced in France may do more to improve the fiscal position of Belgium, as individuals seek to declare income in Brussels rather than Paris. A second issue, in the US at least, is that a substantial portion of the wealthy’s assets are held in private businesses. These are both illiquid and difficult to value. Such challenges aren’t insurmountable. Some assets, property for example, cannot be transferred across border. And, in Switzerland, 5% of government revenue is generated via modest state taxes on wealth above canton-specific thresholds. Other countries might take note. In the US, it is estimate that such a system could generate over US$200 billion.

Despite the difficulties mentioned above, and current low levels of public support, wealth taxes may in the future become the least bad option for some. In the years ahead, already-stretched public finances will face further pressure from the dual headwind of increased healthcare and pension costs. Meanwhile, future technological advances may lead to even greater wealth concentration. (For more, see ‘How technological change drives inequality’) All the while, persistently weak productivity growth risks capping income gains for many. If so, it’s possible to imagine support for increased wealth taxes rising. For the owners of American sports franchises, that would be no laughing matter.