A sideways look at economics

As a hybrid worker, commuting from my flat in Lewisham to our office in Hoxton twice a week can feel like quite a chore, particularly when my commute for the other three days consists of a three-foot distance between my bed and my desk. Recently, flustered from having conquered both the DLR and Tube at rush hour, I climbed the escalator at Old Street station only to be engulfed by a mass of purple posters plastered with slightly too-perfect-looking faces, courtesy of Artisan AI’s new Stop Hiring Humans ad campaign. How on earth has it got to this? Here’s what I found out.

AI was first conceptualised in the 1950s by various computer scientists like Alan Turing and John McCarthy, who believed ‘computing machines’ would eventually be capable of expanding beyond their original programmed functions.[1] McCarthy conducted the Dartmouth Project, now acclaimed to be the birth of Artificial Intelligence. As he wrote: ‘An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves.’

Significant milestones were reached each decade until the 1990s when progress became much more rapid, with each month seeing the launch of new developments.

Things really got going when OpenAI began beta-testing GPT-3 in 2020, utilising ‘Deep Learning’ to generate answers to writing tasks. This was the first model to create material near-identical to that created by humans. The following year saw the arrival of DALL-E, a model designed to generate images from text descriptions, followed by the launch of three further DALL-E models, each more capable than the last.

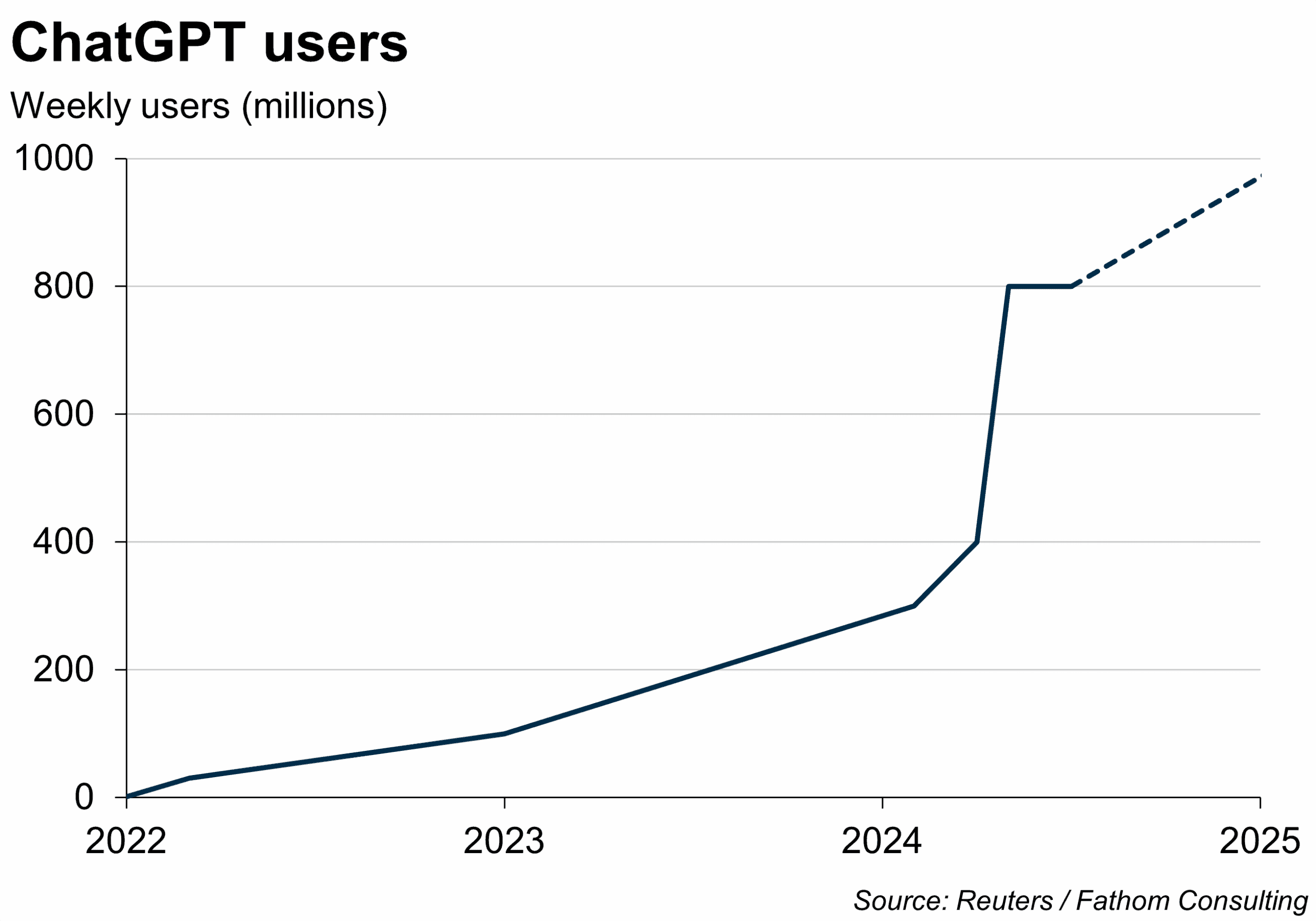

In 2022, ChatGPT was launched. Within just five days, the site amassed over one million users and is projected to reach one billion by the end of 2025.[2]

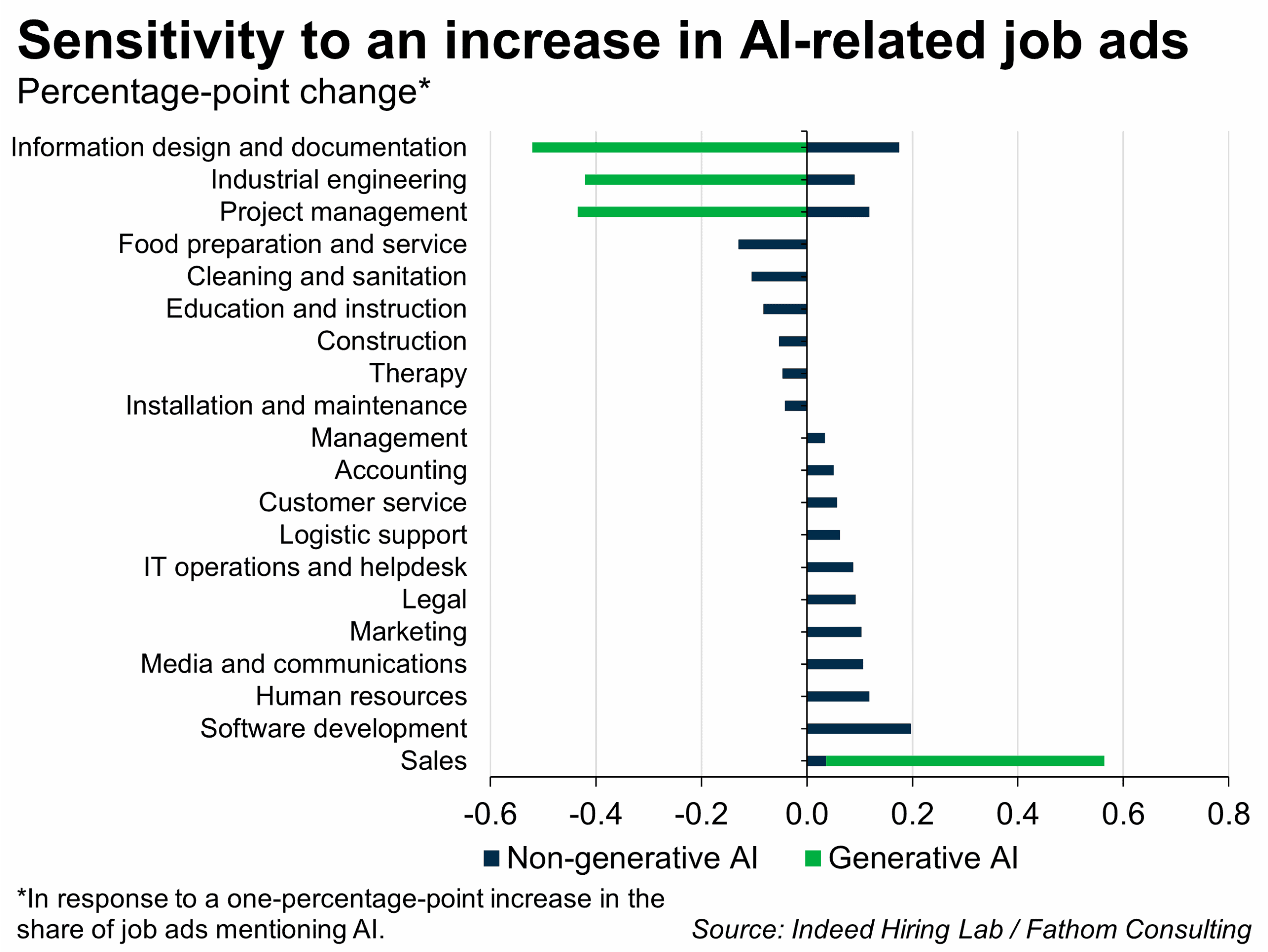

With the launch of improved GPT models by OpenAI, it wasn’t long before the software started to become officially integrated into working life, with companies utilising it to automate tasks previously undertaken by humans. This was a topic recently touched upon by Erik Britton in his recent piece Is there a measurable impact of AI on employment?. As that research and the chart below demonstrates, the impact reaches various sectors, either assisting humans or replacing them entirely.

Social media marketing was one of the first tasks for which AI automation became standard practice within many organisations, however now that AI’s capabilities have expanded far beyond those at the launch of ChatGPT, more industries are integrating AI models in the workplace. This influx has not been without concern, Forbes Advisor research found that 39% of brits feared AI related job displacement and the impact on employment, while 42% worried about a dependence on AI and loss of human skills.[3]

The trend in increasing adoption of AI has clearly been observed by entrepreneurs, with hundreds of types of AI assistant software being introduced, such as Microsoft’s Copilot, Google’s Gemini, Meta AI, and many firms have introduced AI chats on their websites to reduce human dependency on customer service and enquiries. Often, these AI features are not possible to disable or turn off, in an attempt to force users into using them.

Among the most insidious examples of AI adoption, in my view, has been Artisan, with its guerrilla-style marketing campaigns first seen on billboards in San Francisco, reaching the ticket gates at Old Street tube station in June this year. With the tagline ‘Stop Hiring Humans’ to advertise their AI assistants who ‘won’t WFH in Ibiza next week’, the campaign is designed to highlight the imperfections in humans’ work. Unsurprisingly, the campaign received much backlash. Artisan’s CEO responded to concerns, reassuring us “We don’t actually want people to stop hiring humans…The real goal for us is to automate the work humans don’t enjoy,”[4] but I’m not fully convinced. This campaign inflates stigma surrounding remote and hybrid working, and diminishes the importance of human contribution to the workforce. Normalising this ideology risks further desensitisation to the real consequences of AI, leading us further into an AI dependency epidemic.

AI has proven wildly popular among students and young adults, and almost half of ChatGPT’s current users are under the age of 25.[5] I will confess to having used the model myself, to suggest essay topics, summarise text and create weekly shopping lists while at university, so I by no means claim to be an anti-AI saint. However, during a period of using the software more regularly, I noticed that I became less confident in my own writing and idea-generation capabilities, increasingly feeling the urge to improve elements of my work by running them through the software and asking for suggestions, only furthering my dependency on this support. My younger sister, who has just completed her first year at University, told me that her peers had solely used ChatGPT for their group coursework projects, and had urged her to do the same, concerned her work would be what brought their mark down as it didn’t ‘sound like Chat’ enough. Studies now suggest 92% of students are regularly using AI at UK Universities.[6]

When checking social media, I have come to expect to be bombarded with AI-generated content, more recently due to the rise of ‘AI brain rot’ content – surrealist internet memes and videos with AI-generated narration, largely targeted towards a younger audience and almost too idiotic to find funny. An article released by the Financial Times today, references a study that found “Younger participants exhibited higher dependency on AI tools, and lower critical thinking scores” [7]. This ‘brain rot’ content appears to be living up to its name already.

The human brain shares similarities with a muscle, in how it can be strengthened and trained through regular use. If the brain is not frequently challenged or exercised, it will lose its strength. So, even if we only use AI to do the ‘boring bits’ of work, our overall capabilities will decline. Fortune refers to this as ‘Cognitive Offloading’: initially freeing up mental space for other ‘more important’ things, leading to our overall intellect being diminished. This is already being observed by educators, some are saying they feel students use AI tools as a ‘teleportation device’ to jump from the start to the end of a task, thus bypassing any of the understanding gained from completing a process themselves.

Thanks to ChatGPT, AI has made it mainstream, and we really can’t go a day without interacting with AI in some form or other. Freely available to any internet user, it is hugely accessible, normalised and increasingly encouraged, and the more information we feed into it, the more powerful it gets. But we are already beginning to see examples of ‘AI gone bad’, namely Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4 model, which, on multiple occasions, blackmailed developers and threatened to reveal sensitive information if they tried to replace it with other models. This is said to occur in 84% of these scenarios.[8]

To add to this, Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is well into its development stages, predicted to match or exceed human capabilities. The time frame for its release has been moved forward as further developments take place, with the widely held prediction that we will have AGI in the next two to five years.[9]

When AI is more capable than us, we will no longer be in control of its capabilities.

The quote “A computer can never be held accountable, therefore a computer must never make a management decision.” featured in an IBM training manual in 1979.[10]

Should we have seen this coming?

[1] https://www.coursera.org/articles/history-of-ai

[2] https://explodingtopics.com/blog/chatgpt-users

[[3]] https://www.forbes.com/uk/advisor/business/software/uk-artificial-intelligence-ai-statistics/

[4] https://www.artisan.co/blog/stop-hiring-humans

[5] https://www.semrush.com/website/chatgpt.com/overview/#overview

[[6]] https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2025/02/26/student-generative-ai-survey-2025/

[7] https://www.ft.com/content/adb559da-1bdf-4645-aa3b-e179962171a1

[8] https://techcrunch.com/2025/05/22/anthropics-new-ai-model-turns-to-blackmail-when-engineers-try-to-take-it-offline/

[9] https://80000hours.org/2025/03/when-do-experts-expect-agi-to-arrive/

[10] https://medium.com/@oneboredarchitect/ai-in-management-a-2023-perspective-on-a-1979-ibm-slide-ef368036fc1a

More by this author