A sideways look at economics

‘MAN + VAN’ read the sign. ‘Cheap removals, Garden Waste, Student Moves, Gumtree Ebay/IKEA Pick up’. Phone number. This was my man, I thought, my Ford Transit driver in shining armour. My man with a van. I dialled the number, hope welling up. But alas… “£100 for the hour, plus petrol, and a little extra if you need help getting it up the stairs.” I’d heard enough. One piece of furniture! What did I do to deserve such an unfavourable quote? There had to be something at fault, didn’t there?

Vans are crawling the streets these days. There are now more than 4.6 million licensed vans in the UK, one for every 15 Brits, and they account for almost a fifth of all motor vehicles. This 64.3% increase in vannage since 1998 isn’t at all surprising given the gargantuan rise in e-commerce. Vans are the heart and soul of the logistics industry, especially when it comes to last-mile delivery. Vans also keep the construction industry moving. An estimated 54% of vans are primarily used for carrying tools, materials and other equipment. AI may transform a wide array of sectors in the not-so-distant future, potentially displacing millions of workers, but the only intelligence threatening the careers of van-driving plumbers, electricians and builders is… that of a tool-pilferer.[1] A variety of other van specifications exist in the UK: food, waste, ice cream, camper, cara, mini. But one type vanquishes them all — the man with a van.[2] Since these servants to the people are known, at times, to operate in that informal grey zone where HMRC rarely treads, I had assumed my man would offer me an agreeable price. So, how much was my request actually going to cost them?

First the distance, 11 miles door to door. Then the miles per gallon (mpg); vans achieve on average 25 to 45 mpg, but for the man’s sake let’s go with the lower estimate of 25. Dividing 11 miles by 25 mpg gives 0.44 gallons for the trip. The current price of diesel in the UK is approximately 142.18 p per litre, which equates to a per gallon price of £6.46, resulting in a fuel cost of approximately £2.84 for the journey.

Next, labour. The furniture in question was an armchair, not exactly the lightest of seats on the market. Two people would be required. Citymapper estimated the trip would take about an hour. Adding on a reasonable 15 minutes either side for loading and unloading, I was looking at around £41.55 in wages if one assumes the van driver and his assistant both earn the London living wage (£13.85 per hour).[3] By adding on an extra £6.93 to account for the 50% probability of a thirty-minute traffic jam, this lifts the total wage bill to £48.48.

Next, according to insurance price comparison website Go Compare, the median cost of annual van cover in London in August was £790. Dividing that tally by the 253 working days over 2025 gives me a daily insurance premium of £3.12. Finally, ULEZ and CC charges. I’ll add a third of the expected cost (£9.17!) to my calculation Assuming the van was fully paid for, in a good quality condition (which would admittedly make my fuel efficiency calculations obsolete), I couldn’t see any additional costs.

So, all together my estimated cost comes to… £63.61 — meaning the ‘MAN + VAN’ was making a minimum profit margin of 36.4%. Or in other words, he was earning around £57.18[4] for the service. What’s going on here then?

In a perfect world, one might consider the ‘Man with a Van’ market to closely resemble that of perfect competition. For the readers of a non-economics background, perfect competition is a theoretical microeconomic market structure with numerous buyers (those demanding a ‘Man with a Van’ service) and sellers (anyone with a van offering that service). The other key characteristics of perfect competition include:

Identical products: each seller provides an identical service

Freedom of entry into or exit from the market: if anyone has a van, they can offer a ‘Man with a Van’ service

Perfect information: all buyers and sellers have complete knowledge about prices and service quality.

Within this framework, sellers are ‘price takers’, meaning they have no influence over the price paid for the product. A quick thought experiment can help to illustrate this.

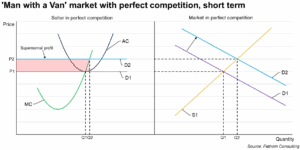

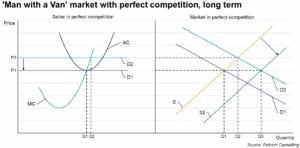

Simon is one of many with a van in London. Suppose the market demand for a uniform ‘Man with a Van’ service increases (from D1 to D2). In the short run, Simon will enjoy a higher price (P2) for the same service while his costs remain unchanged, allowing him to earn an abnormally high (supernormal) profit. However, Jeremy, who also owns a van, has perfect information of this. There’s nothing stopping Jeremy from entering the market and also enjoying supernormal (albeit slightly lower) profits for the same service. Unfortunately for Jeremy, Mark is also wise to this, as are Sophie, Alan, Jeff, Suzanne and just about anyone else willing to provide this service. So, as the market supply of men and women with vans increases (from S to S2), the market price for the service is pushed downward. Eventually, Dobby realises that, since she cannot influence the market price, she must simply choose to supply the quantity of service where her marginal cost (the increase in the cost of serving one more customer) equals that price. In the long run, this process continues until every seller only earns normal profits — the minimum level of earnings required to cover costs and continue operating ‘Man with a Van’ services.

Alas, even a macroeconomist can tell you that this is, for the most part, utter Walrasian nonsense. The service provided by anyone with a van certainly isn’t identical across the board, in quality or construct. Unless my armchair suddenly became a must-have item, I certainly doubt everyone in the UK is demanding a service indistinguishable to mine. While van ownership is pretty high in the UK, the barriers to entry aren’t exactly null and void. And finally, information is anything but perfect in the world of van-aficionados, especially for those who operate within the cash-in-hand economy. Indeed, despite my grievances, the market is far more likely to be somewhere between monopolistic competition and a oligopoly; there are still many sellers, but with each one providing a slightly differentiated service, allowing said sellers a degree of control over the price they charge…

So, looking back on the ‘MAN + VAN’ man I’d spoken with, maybe his quote wasn’t as ridiculous as I’d first imagined. Digging deeper, I discovered £100 wasn’t even on the expensive side of the distribution. Delivery and removal services with seemingly authentic reviews charged a far higher premium since they could successfully signal their non-lemon[5] status. And after all, the service I was looking for not only required transportation, but also care. This man with a van needed a steady hand, a defttouch, a gentle set of fingers if you will. He had to treat this armchair with the same love and respect as if it were his own. I’d even chuck in another fiver if he complimented me on my taste in furniture. Therefore, with that all in mind, I adjusted my valuation one last time. £20 more, around 15% of the armchair’s value, bringing the total to £83.61.

In the end, £90 was agreed for safe travel, only 7.64% off my estimation. So, has my appreciation for van jockeys been tarnished? Not in the slightest. A fair price for a more than fair profession, keeping the underbelly of the UK well-oiled and running smoothly. Whether you’re a chippie, sparkie, last-mile delivery driver or a general tradie — with a van, it’s like you’ve got an MBA, but you’ve also got a bleeding van. So next time an issue arises at home, or on the road, or even at the vintage furniture auction house, value your Ford Transit cavalrymen equitably — imagine how destitute we would all be without them!

P.S. I’d suggest targeting men with electric vans for removals in London! Or if you dare, DIY for £15 per hour in a Zip van…

[1] According to insurance company Direct Line, up to £40 million worth of tools were stolen in 2024 with 12,414 reported tool thefts coming from vehicles.

[2] Or woman, of course: Fathom used the firm Vangirls to move offices some years ago, and were very happy with the results.

[3] It is impossible to know exactly how many hours the ‘MAN + VAN’ man works per week. Some days, he may be employed less than 7.5 hours, others more. Furthermore, the ‘MAN + VAN’ man probably operates on some weekends and public holidays here and there. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that, over the course of a year, he would work an average of 37.5 hours per week. Therefore, the London living wage is an appropriate estimation for the wage component of this cost analysis.

[4] Assuming the helper was only paid £13.85 per hour and not including the traffic payment of £6.93.

[5] The market for ‘Man with a Van’ services draws many similarities to that of the market for used cars, as outlined in Akerlof’s seminal paper “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism” which explores the concept of how asymmetric information (where buyers know less about the product than sellers do) can lead to market failure.

More by this author