A sideways look at economics

Having grown up in Galway, a beautiful town on the west coast of Ireland, and lived in cities from Dublin to New York and now London, I can’t help but compare places through familiar lenses: public transport, housing, quality of life, the usual things people debate when they move abroad. But only in the last few years, as I started thinking seriously about long-term saving and building wealth as a retail investor, did I realise there’s another very important difference between these places: how the government treats ordinary people who try to invest. And on that front, Ireland isn’t just uncompetitive, it is hostile to retail investors who are trying to build wealth, as this TFiF will show

To understand why Ireland’s investment landscape is so punishing, we first need to look at how exchange-traded fund (ETF) investors are treated in Ireland versus the UK. For most retail investors, ETFs are the simplest and most effective way to build long-term wealth: they offer broad diversification, low fees, and steady compounding that can fund everything from retirement to a first home. Most importantly, they allow the investor not to worry about company-specific risk when stock picking, but simply to ‘invest and forget’.

In Ireland, however, ETF investors face something called ‘deemed disposal’, a rule that forces you to pay tax on gains every eight years even if you have not sold anything, destroying the compounding process over and over again. This tax is currently set at 41%, although the Irish Department of Finance is soon set to cut it – but only as far as 38%. In stark contrast, the UK’s Stocks and Shares Investment Savings Account (ISA) allows savers to invest up to £20,000 a year entirely tax free, incurring no capital gains charges, no dividend tax and no tax on interest earned.

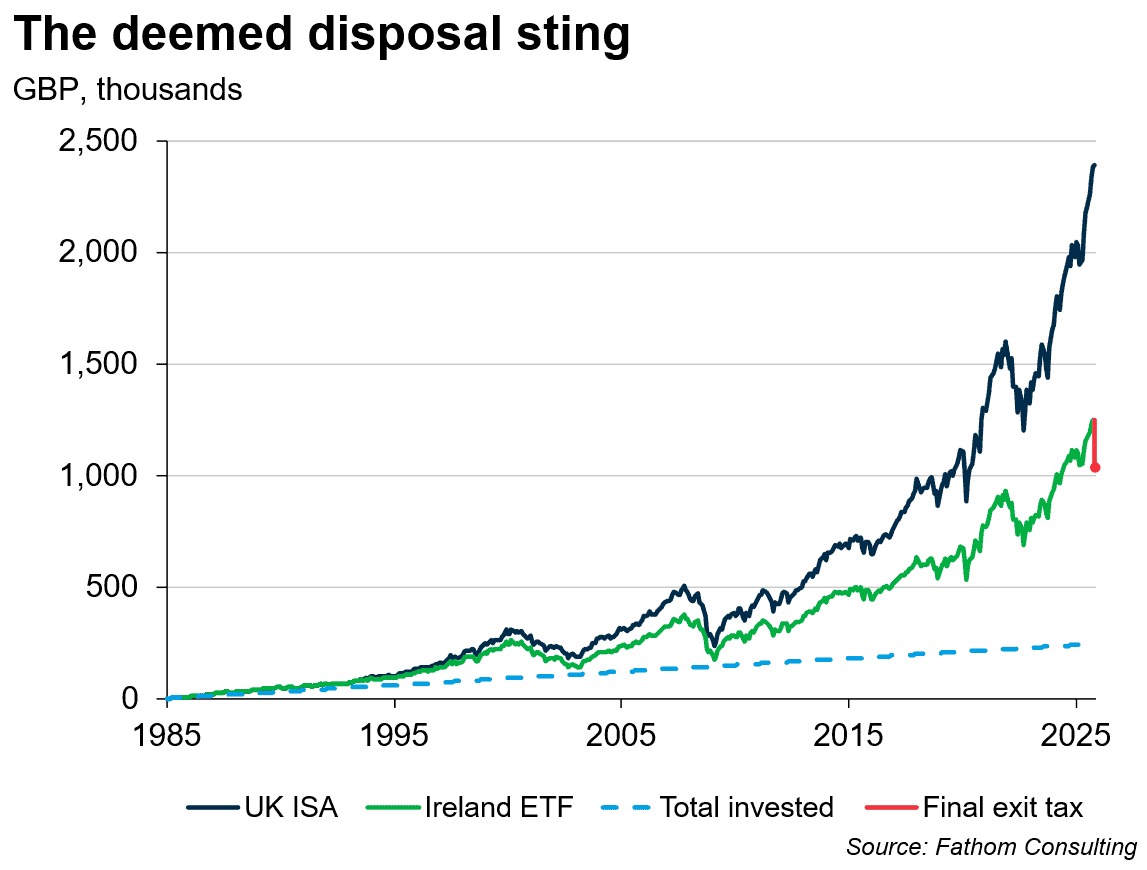

Now let’s look at just how much worse off investors are in the long term under the Irish system, by comparing one investor who allocates from Ireland and is taxed under deemed disposal; with another who invests from the UK and shelters the same contributions inside a tax-free ISA. For this example, we will ignore the effect of exchange rates and assume that exactly £500 is invested each month into the MSCI World Index, a broad and diversified global benchmark. Our period lasts 40 years and follows a hypothetical investor who begins at 25 and stops at 65, using the actual performance of the MSCI All World Index since 1985. (Of course, there is no guarantee that future returns will mirror the past, and indeed deemed disposal was only brought in in 2006, but the purpose here is simply to compare how each tax system treats the same stream of contributions and the same underlying investment.) The difference between the two is captured in the chart below.

The results are shocking. Over the course of 40 years, the Irish investor’s fund is worth over £1.35 million less than the UK investor’s, a difference of more than 56%.We can see how the steady, parasitic effect of deemed disposal weighs on the Irish investor’s capital month by month as time goes on. The £500 that is invested in March 2003 has its gain taxed at 41% in March 2011 and again in March 2019; the following month’s contribution is taxed in April 2011 and April 2019, and so on. This creates a punishing ‘tax drag’, because the money removed early to pay taxes is no longer there to benefit from future compound growth, ultimately causing the total loss of wealth to far exceed the headline 41% tax rate. At the end of the period, any holdings that haven’t been hit by the most recent eight-year charge are taxed once more on the assumption that the investor wishes to cash out, which is why the final value drops sharply along the red line. The UK investor is left with a pot of £2,392,338 and the Irish investor with £1,248,262, which falls to £1,038,673 after deducting a £209,589 exit tax. The code I developed captures all of this logic, but the broader point is unmistakable: Ireland’s approach amounts to a sustained tax raid on responsible savers who are doing exactly what the state claims to encourage – putting money aside for retirement, for a home, and for long-term financial security. It is also worth noting that £500 a month is £6,000 a year, still leaving an additional £14,000 tax-free allowance for the UK investor.

Some Irish investors try to sidestep this system by avoiding ETFs altogether and buying individual shares, but here too the tax regime is hardly encouraging. Normal equities in Ireland are taxed at 33% capital gains, with a tax-free allowance of a mere €1,270 ‒ a number that hasn’t been changed since Ireland left the punt to join the euro on 1 January 2002, at a conversion rate of 1 Irish punt to 1.269 euro. By contrast, the UK’s allowance, which kicks in only after you’ve used up your entire yearly £20,000 tax free allowance, is £3,000 and is taxed at 18% or 24% depending on your income level. The graph below assumes the same parameters as the previous chart, but this time treats the MSCI World Index as a single stock and thus avoids being treated as an ETF and is ‘only’ exposed to the regular 33% Irish capital gains tax. Here, the Irish investor is left with over £700,000 less than the UK investor over 40 years, which could be the difference between affording a decent retirement or not.

Ireland leaves retail investors with a much less effective route to build wealth. It’s also worth noting that, in Ireland, the 40% upper rate of income tax kicks in at an income of €44,000 (about £38,500), compared to £50,000 in the UK. If Ireland is serious about promoting financial literacy, reducing future pension burdens and helping people to save for a home, it needs to introduce a genuine tax-free investment wrapper, an Irish ISA. The fact that two identical investors can end up more than £1.3 million apart purely because of government policy amounts to state-sponsored wealth destruction. Ireland needs this ISA-style system not as a luxury, but as a basic piece of financial infrastructure ‒ one that lets people participate in global markets on fair terms, and build meaningful long-term wealth in their own country. Until that happens, the message to young savers remains depressingly clear: do everything right, invest patiently for decades, and still end up over a million pounds worse off than your peers across the Irish Sea.

More by this author