A sideways look at economics

The Bank of England published this week a working paper that analysed the consequences of issuing so-called central bank digital currency (or CBDC). According to the authors, the macro-economic outcomes seem favourable to say the least – reductions in real interest rates, distortionary taxes and transactions costs could permanently raise the level of GDP by as much as 3%. Drawing parallels between CBDC and Bitcoin, some commentators have questioned whether the Old Lady has adopted the adage “If you can’t beat them, join them”. But CBDC, as described in the Bank of England working paper, and Bitcoin differ fundamentally.

Monetary Economics taught us that it is exceptionally difficult to build a theoretical model in which fiat money has value. The reason, in essence, is that one day the world will end. The day before the world is due to end, money would have no value. Why hold something that is intrinsically worthless, and accepted only by convention as a store of value, when tomorrow there will be nothing to buy? But if, as a non-interest bearing asset, fiat money has no value at a given point in the future, then by process of backward induction it has no value on the day before that either, or – logically – on any preceding day, back to and including today.

But paper fiat money does have value, which ultimately reflects the call that it represents on the assets of the economy whose currency it is. CBDC would have the same backing. In John Barrdear and Michael Kumhof’s paper, CBDC is issued in exchange for gilts, in much the same way as today’s high-powered money is issued against similar eligible collateral. Bank of England notes may be intrinsically worthless bits of paper, but they are at least backed by gilts. Gilts in turn are a liability of the UK sovereign, which has a claim on the efforts of both firms and households resident in the UK through taxation.

Bitcoin, by contrast, is underpinned by nothing. Its value today depends purely on a belief that it will have value tomorrow.

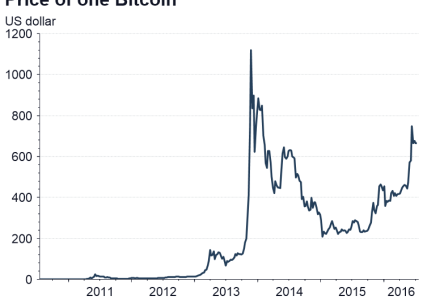

The first Bitcoin exchange was established in early 2010. Prior to that, transactions were negotiated, in an ad-hoc fashion, on internet forums. Legend has it that, soon after its inception, two delivery pizzas were purchased from Papa Johns for the princely sum of 10,000 BTC. By our reckoning, that suggests an exchange rate of around ₵0.3 per Bitcoin. Since then the value has appreciated, significantly!

In the early days, when Bitcoin was circulating – mainly among technology geeks – for a value of no more than a handful of cents each, they were of curiosity value alone. Through 2011 and into 2012, the value of the electronic currency began to take off. This has been attributed to the Silk Road website, a black market for illegal drug dealing. By late November 2013, a single Bitcoin was worth in excess of $1,000. Bitcoins confer anonymity, making them attractive to those dealing in the dark matter of the internet, from drugs to firearms and other contraband (and Papa Johns pizzas).

Proponents of Bitcoin often cite as a virtue the fact that there can never be more than 21 million in existence (the number in circulation today is around 16 million). But rarity itself does not confer value – for example, poems written by Fathom staff are extremely rare, but also wholly without value. Moreover, while the number of Bitcoin may be limited, the number of Bitcoin-like currencies that might be introduced in the future is infinite. Bitcoin are not only intrinsically worthless, unlike fiat money in circulation today they do not even have the implied support of a nation state. Today’s sky-high valuations are puzzling to say the least.

Perhaps it is simply a question of honour among thieves.