A sideways look at economics

Ahead of last season, the Premier League (the top division of English football) announced the introduction of the VAR system. Sadly for us economists, this acronym had little to do with vector autoregressions. No, for football fans those three letters have a very different meaning — Video Assistant Referees. Much to the annoyance of supporters, VARs like to preserve an aura of mystery in their decision-making, and, safely immured in their headquarters at the Stockley Park VAR Hub, they may even surpass the UK government’s SAGE committee in the opacity of their thought processes.

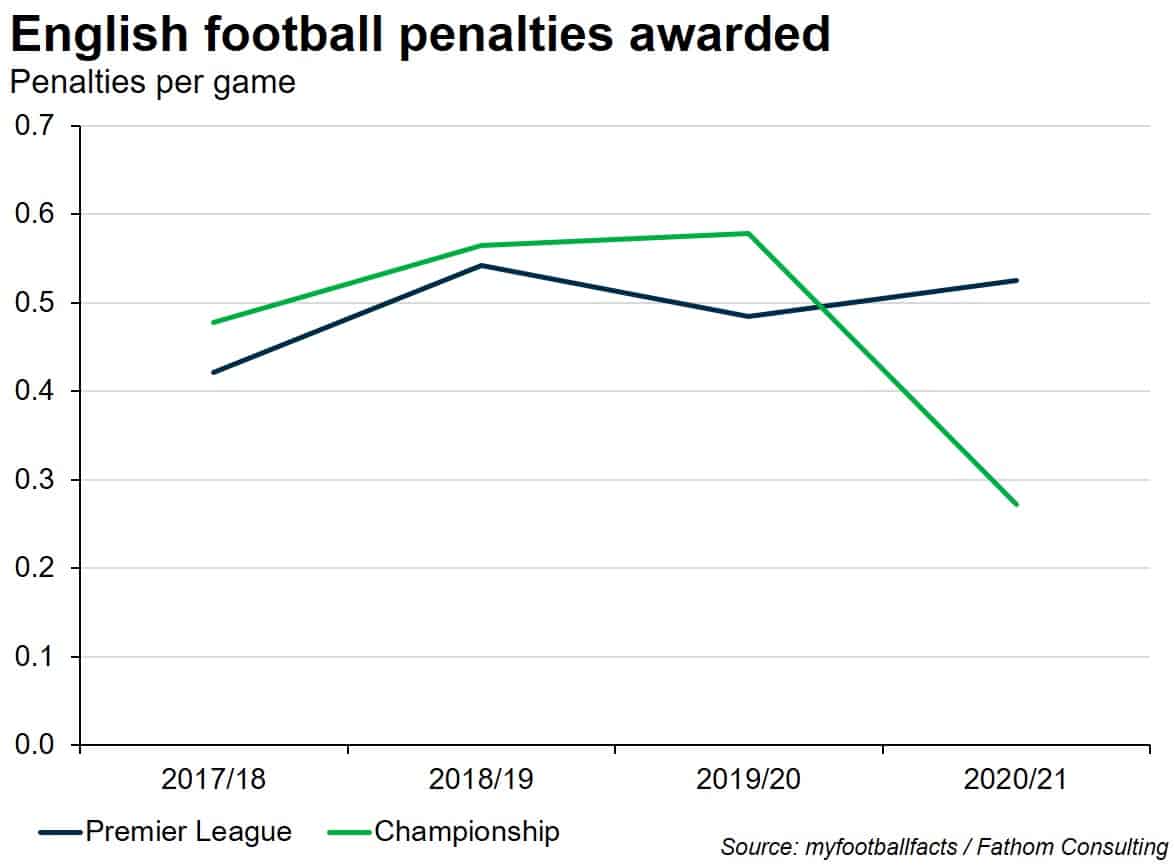

But what impact has the introduction of the VAR system (VAR for short) had on football, besides creating yet another reason to moan at the ref? Well, looked at through the lens of penalties awarded per match played, it’s not immediately obvious that it has made any difference at all. Sure, the number of penalties fell a little during the 2019/20 season, but it remained above the number seen during the 2017/18 season.

Of course, calculating the impact of VAR can’t be that simple; and guess what? It isn’t. Naturally, there are factors aside from the introduction of VAR that influence the number of penalties being awarded, chief among them being changes to the laws of the game. Indeed, a tweak to the handball rule this season was followed by a surge in penalties, with six infringements of that nature (around one-third of the previous season’s total) in the first 26 matches alone (around 7% of the number of games).

But how much of this is due to the rule changes and how much is because of VAR? What we need is a control group. In econometric analysis, the aim is to be able to split your sample in two, with both groups identical in all ways save one: one group receives the treatment and one doesn’t. In footballing terms, what we are looking for is another competition following the same rules as the Premier League but without the use of VAR, to act as the control. Fortunately, we have just such a competition in the form of the Championship, the second rung of England’s footballing pyramid. By comparing changes in penalties per game in the two competitions, we can gauge the impact of VAR. Looking at the lines below, it appears that VAR may actually have reduced the number of penalties awarded last season but increased them this year. That is to say, the impact of VAR may be time-variant, and conditional on the content of the footballing rulebook.

Of course, there is far more to economic analysis than simply “looking at the lines”, but this is a fairly casual piece of analysis, conducted shortly before Fathom’s Friday evening social tradition of Beer O’Clock. Nevertheless, there are plenty of other examples where such an approach has been developed further in order to make important economic inferences. Arguably, the most notable of these comes from David Card and Alan Krueger. In their seminal paper on the impact of the minimum wage,[1] they compared employment in neighbouring US states before and after one state increased the minimum wage. That paper, which used the difference-in-differences estimator (essentially the empirical equivalent to “looking at the lines”), found no evidence that a higher minimum wage reduced employment; and as a result it had a profound effect on the academic community’s attitude towards minimum wage laws.

What’s amazing, given the multitude of empirical models that exist, is that the same, very simple principles used to judge the impact of VAR and of raising the minimum wage can also be used to assess pharmaceutical trials. Indeed, standard practice in vaccine testing sees half the trial participants randomly selected to receive an injection of the vaccine (the treatment group) with the other half forming the control group and receiving a placebo injection that doesn’t include the candidate vaccine. Consequently, there are no concerns about differing characteristics between the control and treatment groups, since both come from the same initial sample of people and neither knows whether they’ve had the vaccine.

This was exactly how the BioNTech/Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine was tested (the same is true for the Moderna vaccine). Their trial featured more than 43,000 participants, with 162 confirmed COVID-19 cases occurring in the control group and just 8 in the trial group, suggesting that the vaccine efficacy is around 95%.[2] While that number remains subject to some uncertainty, statistical tests would strongly reject the suggestion that the vaccine doesn’t work.

And given the profound economic implications of that finding, that is good news indeed!

[1] Card, D. and Krueger, B., 1994. Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The American Economic Review, 84(4), pp.772-793.

[2] For those interested in hearing more about the BioNTech-Pfizer trial, I suggest you check out this blog https://phastar.com/blog/250-statisticians-view-on-pfizer-covid19-vaccine-data