A sideways look at economics

After talking about the economics of planes in my two previous TFiFs, I thought it was about time I pivoted to focus on my other big interest, which is sport. So today I am going to talk about cricket, and specifically, the players’ auction in the Indian Premier League (IPL). This is a subject that has been causing some heartache for me this season, as the IPL team I support seems to have made a mess of the auction and as a result the results have been disappointing to say the least.

For context, the IPL is the largest franchise cricket competition in the world, running for around 2-3 months of the year since 2008. The world’s best cricketers all want to be a part of it, but the 10 franchises that participate only have room for around 250 players. How do they go about deciding who gets to play? It’s done through an auction — every player that wants to play signs up, and the teams meet a few months before the start of the tournament for a grand auction, bidding against one another to offer ever-increasing sums to the players they want.

The money thrown around in this auction is big — life-changing for the cricketers that want to be a part of it. For example, the highest ever bid at one of these auctions was around US $3 million, going to Rishabh Pant ahead of the 2025 season (and that’s just for 2-3 months of work). So far, the season hasn’t gone to plan for Rishabh and he’s struggling to justify that price tag. My own team, the Chennai Super Kings (CSK), are sitting near the bottom of the table, primarily because they have made a mess of the auction and put together a team that doesn’t have the winning formula. Considering how important the auction is to the IPL, I thought it would be interesting to think about it through the lens of the auction theory I was taught during my time at university.

The IPL uses an English-style auction, the ones we have grown up seeing on television, where the auctioneers ask for bids which are called out loud by the participants, and the highest bidder wins and pays what they bid. Auctions are generally designed such that the winner is the one that is prepared to place the highest price tag on the player. To do this, it is important that the auction encourages bidding up to one’s maximum valuation. The English auction method does this: the dominant strategy in this game is to remain in the bidding until your price tag is reached, and leave once bidding exceeds this valuation. Quitting the bidding before reaching your valuation leaves surplus on the table, and bidding past your valuation means you are paying more than you think the player is worth. So, everyone should just bid up to their estimate of how much the player is worth to them, and hope that other teams pull out before that valuation is reached.

This may seem obvious, but it’s not necessarily the case in all types of auctions. A classic example of a different strategy is a first-price, sealed-bid auction, often used in Scottish house sales. In this auction, each party hands to the auctioneer a single written bid inside a sealed envelope, and the winner (the one with the highest bid when the envelopes are opened) must then pay this bid. Because players cannot respond to other peoples’ bids there is an incentive to shade your bid below your estimated value, and so it’s not necessarily obvious what one should bid in this type of auction.

In an English auction, it’s a lot simpler — keep bidding until your estimated valuation is reached and pull out of the auction once it is. So, based on this, what is my first piece of advice to the IPL teams, if they want to avoid the fate of the Chennai Super Kings this year? Do your homework, and have confident estimates of your value for each player before the auction; don’t be shy in bidding up to your estimate; then have the restraint to drop out as soon as the bidding crosses that valuation.

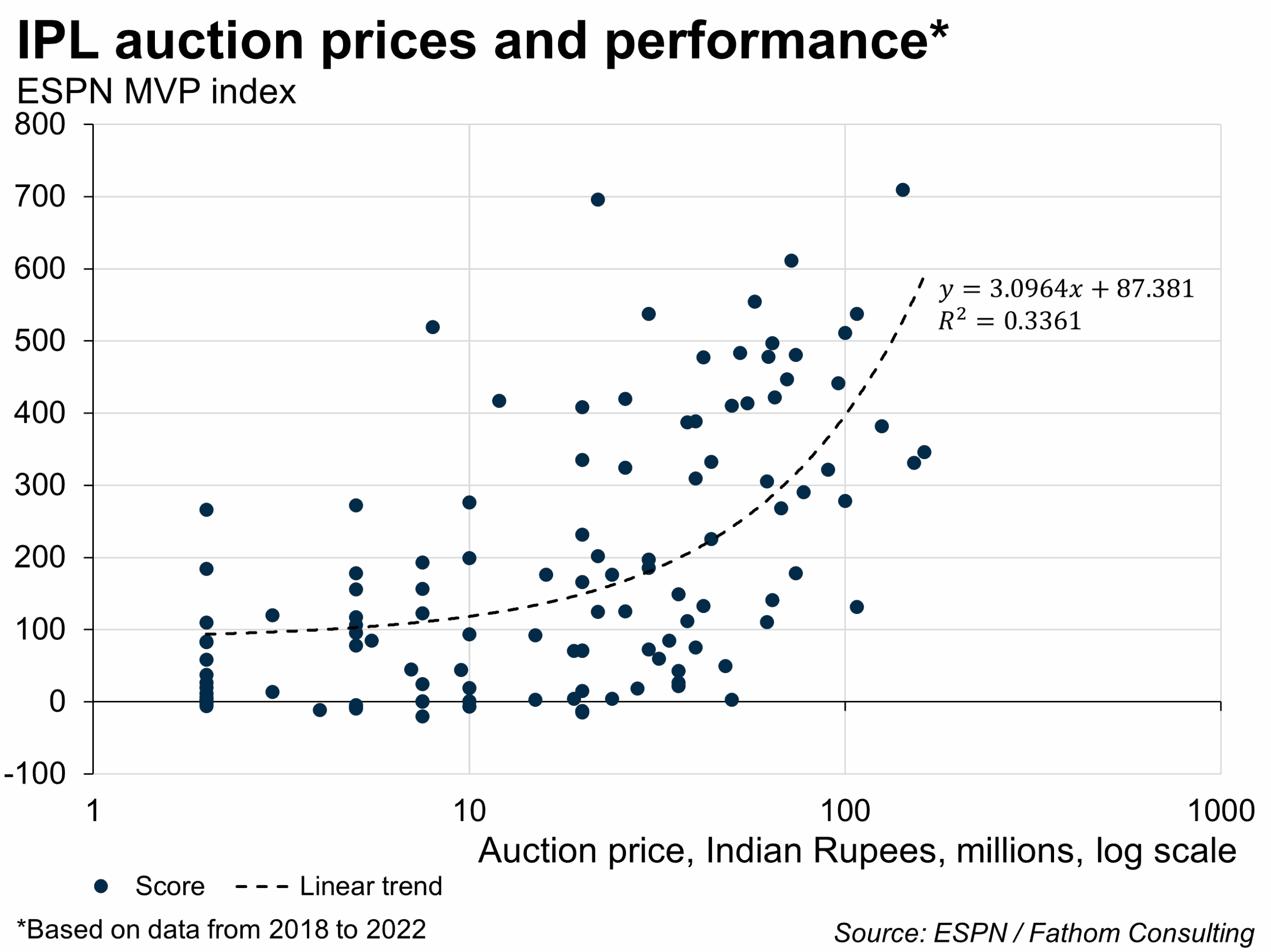

But now, a complication — any ‘common values’ auction is subject to the ‘winner’s curse’. A common values auction is one in which the value of any player is the same for any team, but is only an estimate (i.e., no team knows in advance exactly how a player, like Rishabh Pant, will perform in that season). I think an IPL auction is primarily a common values auction, because generally if a player has a good season for team A, they would probably also have had a good season for team B too. The winner’s curse in this auction is that the team that wins a player is probably the team with the highest estimate of the player’s value — and so they also risk being the team to have overestimated the player’s value the most. A quick analysis shows that player performance does seem to rise with auction price (shown in the chart below), demonstrating that teams do generally get their estimates of player value more or less right. However, there are clearly some expensive mistakes, as seen by the dots in the bottom right of the chart (I’m looking at Glenn Maxwell in 2020 or Chris Woakes in 2018 here). At these points the player’s performance has not really justified the price tag, resulting in the winner’s curse for the team that won the bidding for that player.

The English auction provides teams with a bit of help in dealing with the winner’s curse, in the form of information they can gain from other teams’ auction strategies. So, seeing another team drop out of the auction for a player (especially a team that has historically done well at identifying talent at auctions) should give you an indication of their estimate of the player’s value. Updating your estimates of player value based on this information could help prevent falling victim to the winner’s curse.

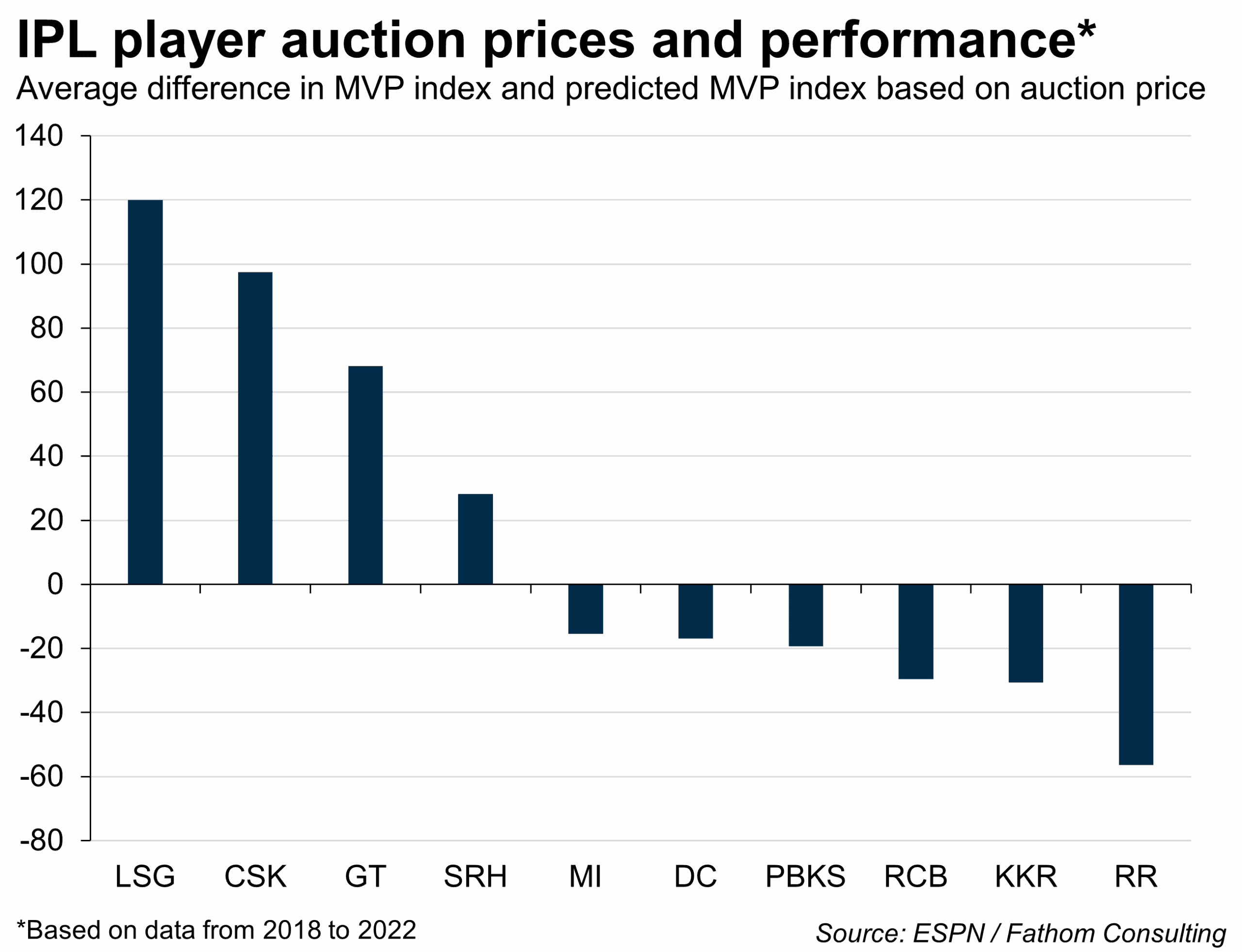

As the chart below shows, in the past CSK has been really good at finding bargains in the auction, so that the average CSK player in this period lies above the trend line in the above chart. So, my second piece advice, for teams at the bottom of the below chart, would be: work out how much you trust other teams’ estimates of player value, and keep adjusting your estimates based on this during the auction to prevent overpaying for a mediocre player or underbidding for a promising player. And for CSK — go back to what we were doing from 2018‒2022, this year’s mistakes in the auction are an anomaly for us!

Finally, there is an argument to be made that the IPL auction is not completely a common values auction, that there is an element of private value. This is because it is possible that a certain player fits better into a team’s existing balance or composition. Their presence in that particular team would raise their own performance higher than it would have been at another team. So, in light of this, I suggest teams work out how best to identify the type of players that are likely to overperform when playing with them as opposed to another team. The value of this overperformance can then top up the baseline estimate of a player’s value, allowing the team to bid more for players that they think are particularly suited to them.

I know that the three points listed above are much easier said than done, and require a rigorous and creative approach… which is why if anyone from the IPL is reading this, I think Fathom has some minds that may be able to help!

Note: The 2025 season of the IPL has been suspended for a week in light of the tensions between India and Pakistan. Here’s hoping for a peaceful conclusion to these events.

More from this author