A sideways look at economics

The film Moneyball tells the story of how a small-market Major League Baseball (MLB) team rebuilt after losing several ‘irreplaceable’ star players. Brad Pitt plays Billy Beane, the general manager of the Oakland Athletics, who hires young economist Peter Brand (Jonah Hill) to help him put together a new data-driven approach to recruitment. Armed with the data, Beane signs a collection of new players who don’t fit the mould of textbook baseball superstars in terms of physical stature, injury records and batting average. The critics scoff, but Beane and Brand have discovered inefficiencies in the player market, and their approach allows them to identify highly effective players at a fraction of their perceived cost. Against the odds, the side matches its outstanding performance from the previous season and sets a new American League record with 20 consecutive wins. The story is compelling, but what makes Moneyball truly fascinating is how far its lessons have spread beyond baseball. Do data analytics truly allow small-market teams to be victorious?

Moneyball is a true story — aside from some Hollywood flair — based on the 2002 season of the Oakland Athletics (commonly referred to as the A’s). The system that Beane and his assistant Brand (based on real-life figure Paul DePodesta) developed at the A’s is known as sabermetrics.[1] Sabermetrics may sound like a statistical spin-off of Star Wars, but it revolutionised how sports performance is measured; instead of relying on traditional stats like batting average, sabermetrics employs advanced metrics that provide a more accurate picture of a player’s true value, helping teams uncover undervalued talent.

One such metric widely used in the movie is On-Base Percentage (OBP). In baseball, a player gets ‘on base’ when they reach first base (or further) safely. This could be by hitting the ball, drawing a walk (four bad pitches they don’t swing at), or being hit by a pitch – ouch! Traditional stats like batting average only count hits, but OBP captures all of the ways a player avoids getting out. For example, if a player comes up to bat ten times, gets three hits and one walk, their batting average is 33%, but their OBP is 40% – showing a fuller picture of their ability to get on base. The Oakland A’s used this stat to spot players who consistently got on base but were overlooked by teams focused on physical factors and conventional metrics, helping them build a more competitive team on a limited budget. The A’s matched the Yankees for regular season wins in 2002 – 103 each – with a budget three times smaller!

While the movie focuses heavily on this idea of ‘getting on base’, the real key to sabermetrics is all about maximising the number of wins in a season, whilst minimising the cost of players. It does so through a system of comparing one player’s strengths against another that might replace them — a concept called Wins Above Replacement, or WAR. WAR helps teams measure how much a player contributes to their number of wins, allowing for a more complete analysis than relying on any one statistic, like batting average or home runs.

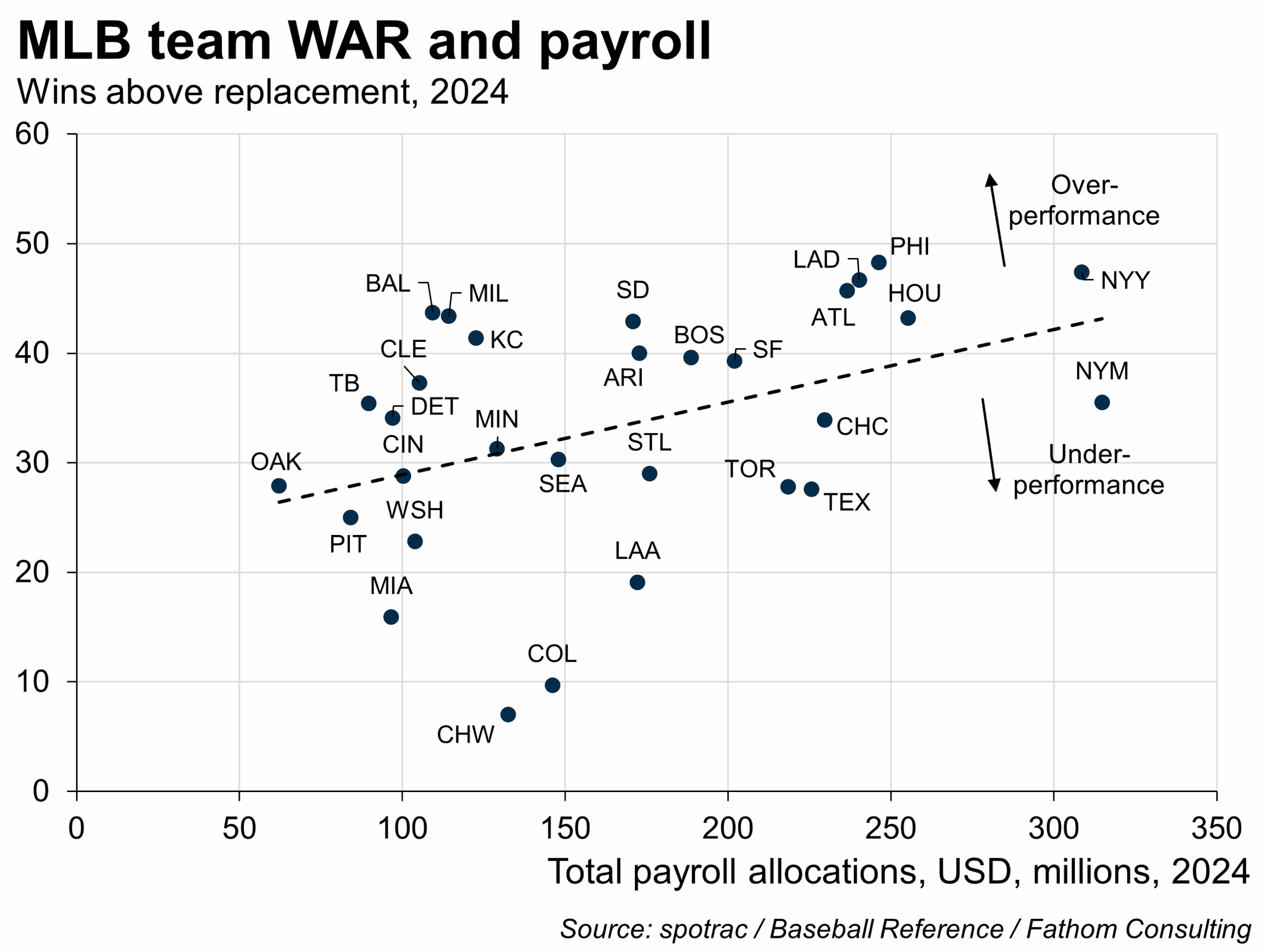

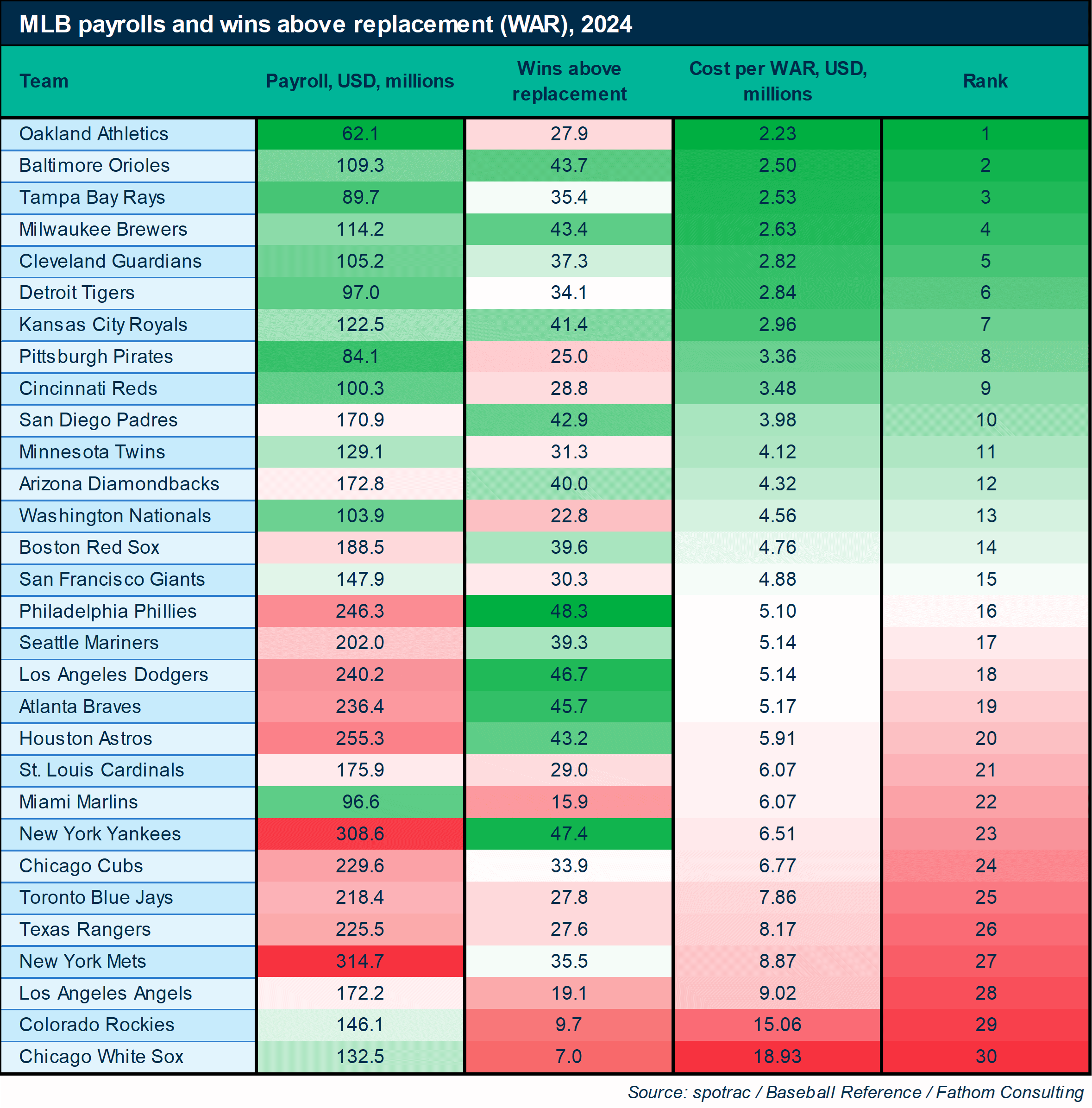

Does it work? To check which team is spending its money most efficiently to generate wins, we can take a look at the WAR in each team across the MLB compared to their payroll. I took a look at the 2024 data:

First, there is clearly a positive correlation between payroll and WAR, meaning that spending more on your team is associated with improved performance. Digging deeper, we can find that some teams have a lower ‘cost per WAR’ (payroll / WAR) than others, indicating the degree of efficiency with which they sign high-quality players.

The Rays, Orioles, and Athletics stood out in 2024 for their efficiency. These teams have three of the smallest payrolls in Major League Baseball, and their performance according to WAR was much higher than payroll alone would suggest. However, getting the most out of one’s payroll doesn’t always translate to division titles or championships. The A’s had the fifth worst record in baseball last year. The Rays had an average season, not qualifying for the playoffs, and although the Orioles qualified through the Wild Card, they lost in the first round to the Royals. The Mets (my team) went even further, and their cost per WAR was the fourth worst in the league.

Football clubs have also begun to take advantage of sabermetrics — with Liverpool FC a very successful beneficiary. Liverpool were bought by Fenway Sports Group in 2010, whose co-owner John W Henry famously tried to recruit Billy Beane to his Boston Red Sox team following the successful 2002 season. They duly appointed Ian Graham to set up a brand-new data research team, which is widely credited with helping Jurgen Klopp bring the club a sixth UEFA Champions League title and an elusive first Premier League crown.[2] Notably, Graham spotted an inefficiency in the valuation of Mohamed Salah; he felt that contrary to popular belief, he hadn’t failed at Chelsea, as his numbers were as high there as they were before and after leaving the club. Graham found that Salah would be a good partner to Roberto Firmino, due to the latter’s high ranking in creating expected goals from his passes. This proved to be correct, with Salah bagging 32 goals in the 2017/18 season — a Premier League record at the time! Avid football fans will know that statistics such as Expected Goals (xG) have become mainstream in media coverage, and whilst not all fans have bought into their value, sabermetrics has undoubtedly changed player evaluation in football.

The principles of sabermetrics and Moneyball have even been adopted beyond sports. In the movie industry, Legendary Entertainment — the studio behind Godzilla and Jurassic World — established an analytics division in 2013 led by Matthew Marolda, a former sports analytics consultant tasked with ‘doing Moneyball for Hollywood.’ Today, every decision at Legendary is data-driven, from forecasting project success to using social sentiment and the Ulmer Scale to identify undervalued actors outside of the typical A-list. Independent studios also apply the concept of Moneyball to find success, by picking up scripts and directors that Hollywood overlooks. They target niche audiences and cater specifically to film critics, rather than chasing typical box-office hits. At the 2025 Oscars, independent studios dominated, with Neon’s Anora winning five Oscars, beating blockbusters like Wicked and Dune: Part Two. Furthermore, Latvia’s Flow embodied the Moneyball spirit, overcoming Pixar’s Inside Out 2 and DreamWorks’ Wild Robot at the awards, having optimised its $4 million budget with lesser-known directing and animation talent, combined with using low-cost, open-source animation tools to achieve success.

The essence of sabermetrics, Moneyball, and WAR is about redefining how we measure value, and using that insight to uncover market inefficiencies that allow underdogs to compete. In asset allocation, investors may apply a Moneyball philosophy by comparing the expected return of an investment against a ‘replacement level’ asset, like Treasury bills or an index fund. By adjusting for volatility and fees, they can identify which assets offer the highest return per unit of risk and cost — like the way the Sharpe ratio measures risk-adjusted efficiency — allowing investors to optimise their portfolio the same way the A’s optimised their lineup.

This logic also applies to geopolitics. The UK cannot match the US and China in terms of military or economic strength, but retains a disproportionately large influence in international affairs through its use of soft power — investing in world-class universities and research, using the Royal Family as a diplomatic brand, and exporting cultural assets like music, theatre and media. In doing so, it continues to punch above its weight on the global stage.

Across sport, business and beyond, the Moneyball mindset offers a way to level the playing field. But while it can bridge the gap, it rarely closes it entirely. In baseball, teams like the A’s can become more competitive, but the depth and star power of teams like the Dodgers and Yankees often proves decisive in the playoffs.

Moneyball’s legacy shows that while efficient spending may not always overcome deep pockets, it gives smaller players a real chance to challenge the status quo — and sometimes, to win.

[1] The term was coined by baseball historian Bill James, based on the acronym for the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) — of which he was a member.

[2] As my colleague was at pains to remind me, prior to the Premier League’s rebrand in 1992 Liverpool had already won 18 league titles. The title in 2020 was just their first since 1990, followed by another in 2025, totalling 20 titles overall.

More from Thank Fathom it’s Friday

Should we be scared of sharks?

Three pieces of advice on IPL auctions