A sideways look at economics

It has become a Fathom tradition that, upon returning from holiday, Fathomites will write a blog post tangentally related to their travels. I recently came back from a trip to Taiwan and it’s the nation’s capital (or more precisely its tallest building) that serves as the inspiration for this week’s blog.

For those who don’t know, Taipei (the capital city of Taiwan) plays host to the Taipei 101 tower, once the tallest building in the world. On the face of things, it might seem odd that the country has such a colossal building. Indeed, the country only has a population of around 20 million people and represents just 1% of global GDP. And yet, even now, the bamboo-shaped building ranks as the eleventh tallest building in the world. This observation piqued my interest and got me wondering about the extent to which economics can explain the location of the world’s tallest skyscrapers…

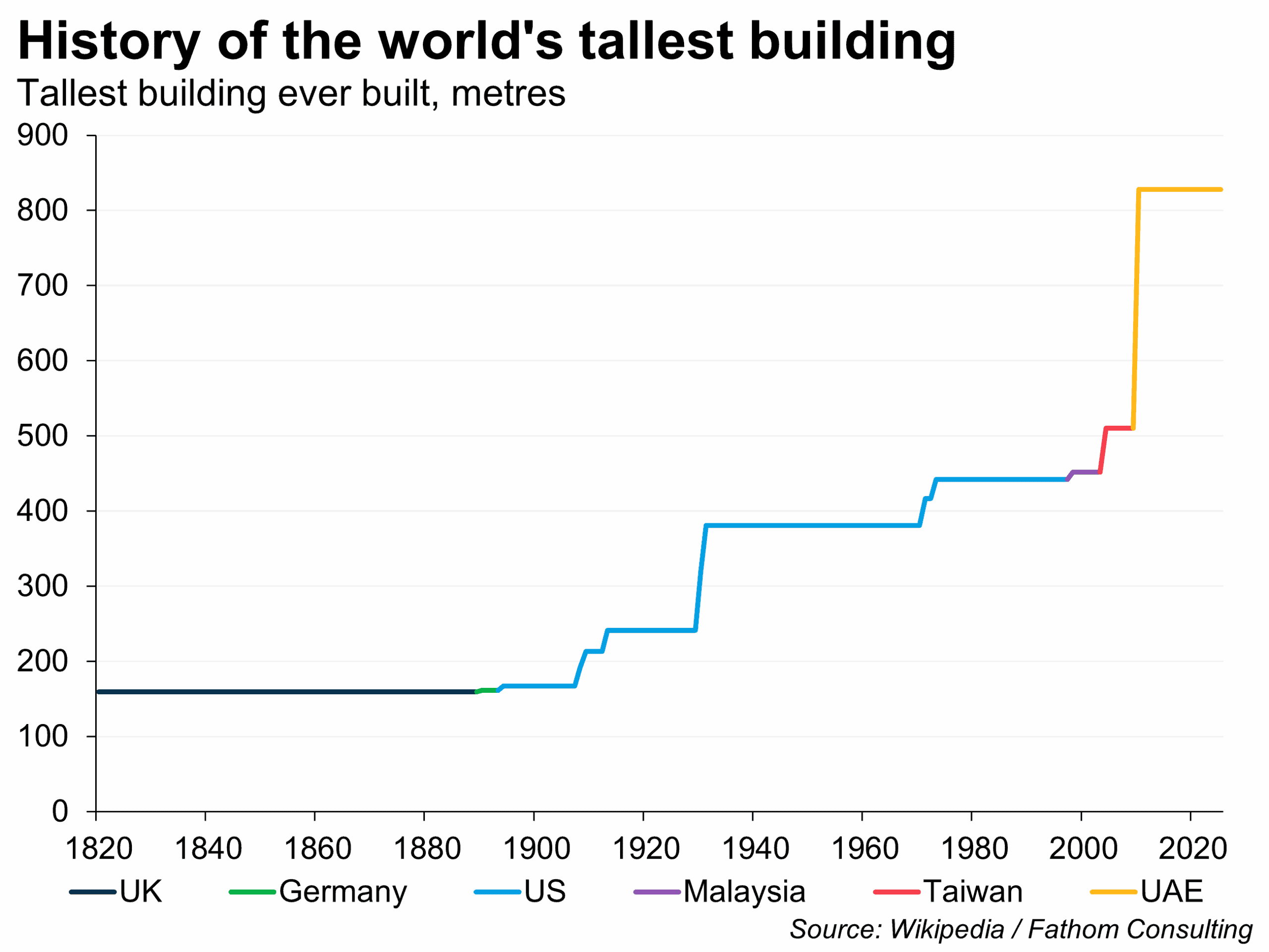

To test this, I compiled a list of the world’s tallest buildings over time, but not before falling down a rabbit hole into the debate of buildings versus structures. (For those few nerds wondering about the distinction between the two, the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat defines the former as both having floors and being designed for residential, manufacturing or business purposes — this definition apparently rules out both the Washington Monument and the Eiffel Tower.) Looking at the chart below, you can see how this concept has evolved since 1820.

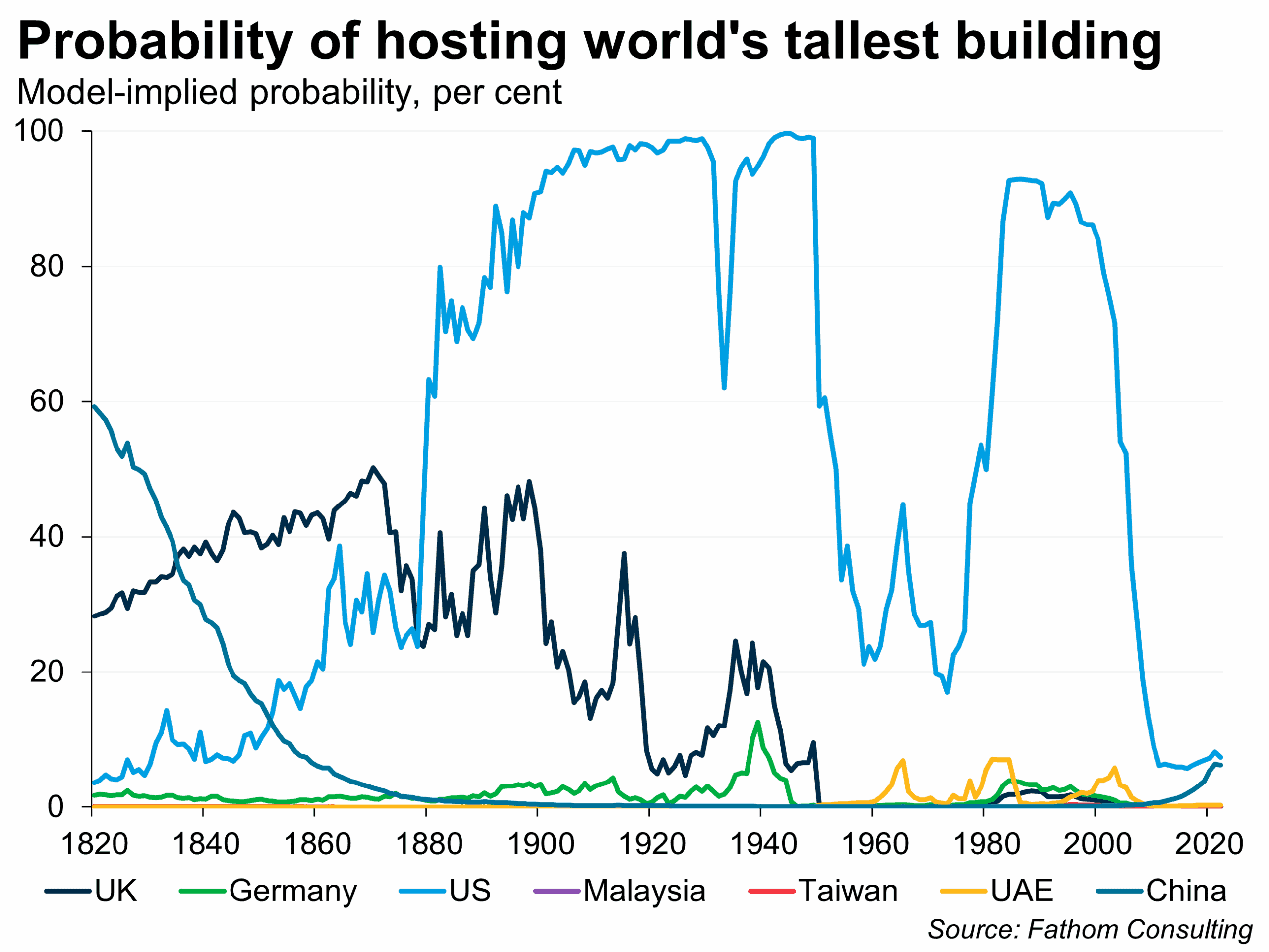

Having compiled this list, I then tried to explain the holders of this title in a regression model with just two explanatory variables — a country’s share of global GDP and its level of GDP per capita (relative to the global maximum). These two indicators were chosen to reflect a country’s size and its income status. To my surprise, this relatively simple model achieved an R2 of around 65%.

Taking these results, we can see that it should not have been a surprise that the US played host to the world’s tallest buildings between 1894 and 1998. Nor should it have been a particular surprise that the UK held the title before that. But the two subsequent hosts (Malaysia and Taiwan) appear to be more of a surprise — you cannot explain their holding of the title on the basis of this relatively simple model. What might explain it? Pre-Asian Financial Crisis exuberance? Or perhaps it might simply have been the use of large-scale construction projects as a means to generate soft power?

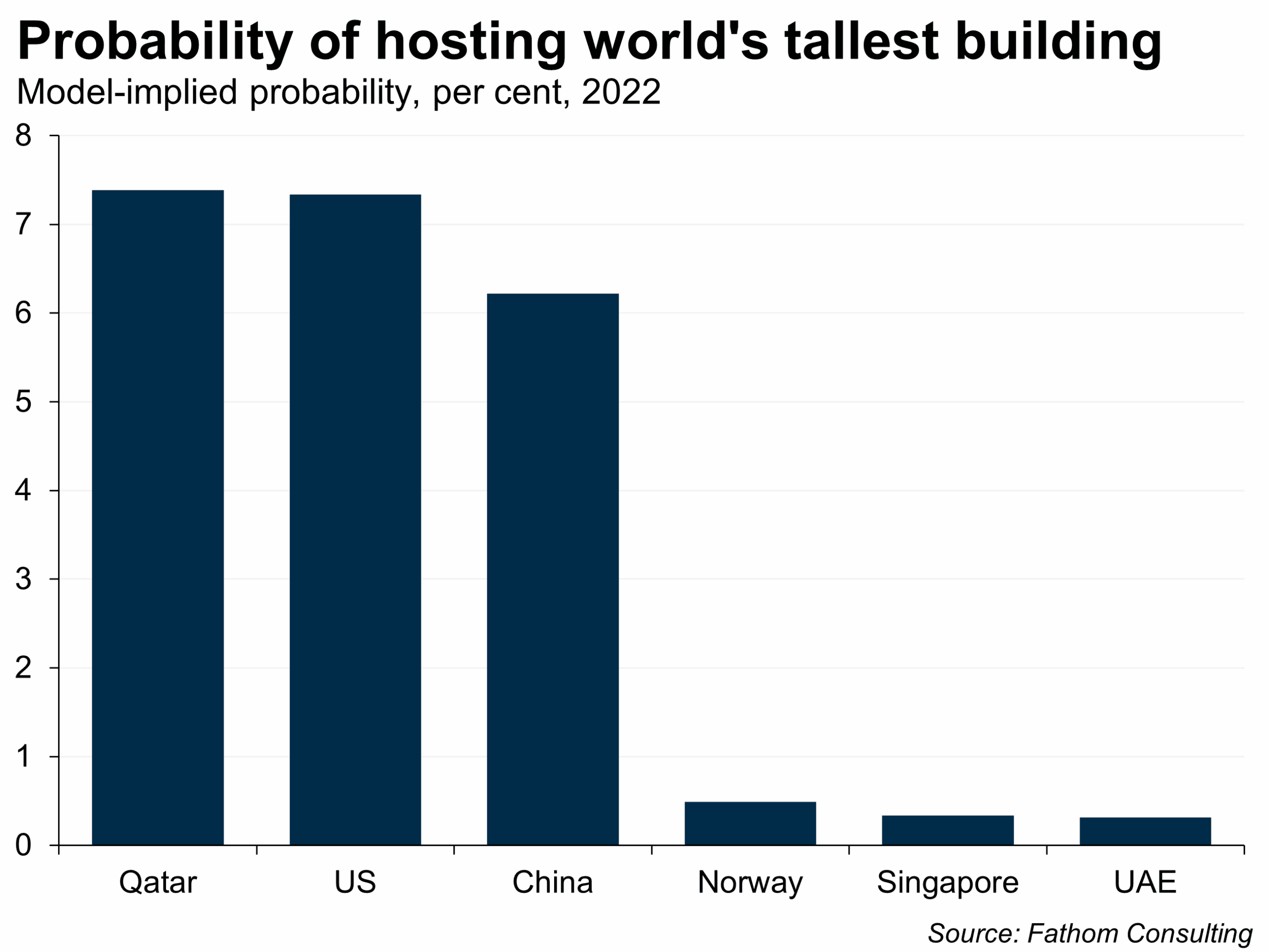

Turning to the current period and the model finds it relatively hard to predict where the world’s tallest building is likely to be located — no individual country currently has a greater than 10% probability of holding that title. This likely reflects the fact that past record holders were typically the global economic hegemons of their day (and also among the world’s richest countries) but that nowadays no single country can claim that title unchallenged. Notable in this context is the US, which for most of the past 200 years was the likeliest country to hold the record, but it has subsequently seen its probability of holding that title drop dramatically from the late 1990s onwards (roughly when it lost the record). It now sits second in the model’s rankings to Qatar (a country that, rather than targeting tall buildings, focused its engineering energies on building numerous state-of-the-art football stadiums for the 2022 World Cup).[1] China rounds off the top three with the record of the world’s tallest building being one feat that has thus far eluded the world’s second largest economy.[2] The UAE, home to the Burj Khalifa (the current record holder), places just sixth on the list reflecting that, at least in part, the decision to build there was likely motivated by a desire to boost the country’s tourism industry.

So, what have we learnt? Historically, it has been relatively easy to predict the nation playing host to the world’s tallest building, but more recently the signal that the model sends has become less clear. Perhaps tall buildings no longer represent a frontier technology. Perhaps they’re now something that any country can build, and it’s only the appetite to do so that counts.

[1] It’s worth noting also that China did something similar when hosting the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

[2] It should be noted, however, that another way of classifying tall buildings (according to the elevation of its highest occupied floor) would have placed the Shanghai World Financial Center at the top of the list in 2008.

More by this author