A sideways look at economics

On the Monday just passed, I was faced with one of my pet peeves. As part of my ongoing effort to explore the less-pricey offerings that London has on offer, I hopped on the tube to Canary Wharf to explore the Canary Roof Palace Gardens for the first time, having enjoyed the Barbican Conservatory a few months earlier. While exploring the shopping centre there I encountered a much hated obstacle that I just had to face.

Stairs.

This was not just any set of stairs, however. As a matter of fact, I actually enjoy walking up stairs over the alternatives — i.e., straight-up climbing, which is a tad too physically excessive for an everyday stroll, or any stroll for that matter. But no, not those stairs. This was a broken-down escalator.

Approaching the dull, grey, lifeless steps, assessing the rough time I would have to endure the horror of negotiating them, while scanning for an alternative normal ‘manual’ stair, to no avail, I braced myself for what was to come. That feeling that sticks around for the rest of the day. That numbing, heavy and unbalanced sensation that would seize up my knees and legs. There was no avoiding it and, if I wanted to go up to the next level without taking a very convoluted ‘scenic’ route, I needed to proceed with my climb.

But why? Why? I have encountered this many times. I know the escalator is broken. I know it is now essentially just a set of stairs. Nonetheless, despite there being no logical reason, they induce in me a sense of unease and leaden resistance. Why should a metal set of moving stairs, broken and now inert — like any other regular staircase — cause such a reaction?

Some may say an escalator has a different height and depth of steps, and that the sense of support is different, however, this is the same for many staircases — whether at your own home, the homes of friends and family, in shops or temporary metal steps at events — they are very rarely identical and require adjustment to gait and balance, yet, I cannot recall feeling the same uneasiness.

Wanting to get some insight — yes, this bee in my bonnet did bother me to that extent — I asked Google to shed some light on my condition. It appears that this is a known scientific phenomenon — aptly called ‘The Broken Escalator Phenomenon’. A study from 2003 replicated the situation using a sled. The main experiment involved measuring the walking velocity, forward sway and EMG signals when boarding a static sled ten times, followed by a moving sled twenty times, and then informing participants the sled would remain static and boarding the static sled ten times again. Due to the experience of the moving sled and the brain’s recent experience, much like a moving escalator, even knowing the sled would remain stationary, prior experiences of movement meant that participants accelerated their pace when walking onto it and leaned forward to balance as if it were moving. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12802549/) This led to the researchers’ conclusion that locomotor adaptation may be more impervious to cognitive control than other types of motor learning.

From my standpoint, I have broken the problem down into three components:

- The brain knows from experience that escalators are a moving system

- I see a broken escalator that is not moving and I am fully aware that I can walk up or down it like any other staircase

- Despite this knowledge, my brain unconsciously prepares my body position (forward- or backward-lean) and gait etc. for the escalator’s movement based off my prior experiences

The study also found that participants did adjust back to the sled being stationary, but that it took time to adjust, essentially for the feeling of walking up a broken escalator to converge to that of a regular staircase — or in the study’s experiment the body’s response to stepping on a static sled to revert back to baseline subsequent to stepping on a moving sled and then being informed the sled would remain static.

Parallels to these responses extend beyond the broken escalator and into broader human behaviour where your brain is wired based on certain expectations and rules of thumb to simplify the everyday decisions and actions modelled from your experiences to date. These rules of thumb tend to adapt to your experiences: but slowly, stickily. If, for example, after food shopping, you find you have picked up some food with a short shelf-life, you might tend to be more careful afterwards, at least in the near-future, in my experience. Especially if you’ve done that two or three times in a row.

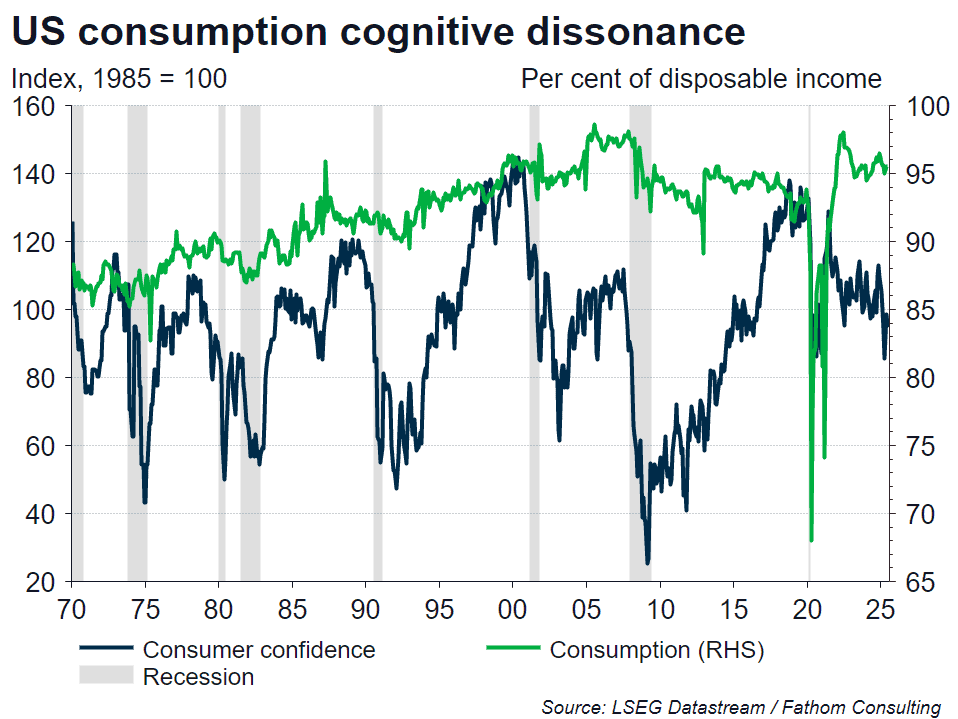

There are other real-world circumstances where a misalignment between beliefs and end behaviours, and resultant cognitive dissonance, persist. The chart above depicts the frequent disconnect between consumer confidence and consumption. Despite big negative hits to confidence during recessions (the grey shaded areas in the chart), which typically are reflected in elevated risk aversion, at times households have seen their own financial circumstances remain strong and have raised consumption accordingly. But during the Global Financial Crisis households’ feelings and their behaviour moved more closely together: following a substantial and prolonged hit to consumer confidence, spending drifted down as a share of income for many years. Households reduced the share of their budget allocated to consumption, choosing to accumulate more savings instead: no cognitive dissonance in that case (https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp1242.pdf). If the shock is big enough, our expectations come into line with our behaviour.

So next time you get that uncomfortable sensation when climbing those static metal steps, remember there is a psychological reason and that its origin is not unique to you. It’s not just a micro issue, pertaining to you alone. It’s a macro issue too.

More by this author