A sideways look at economics

Last year, I wrote a TFiF that was published on Valentine’s Day. I didn’t take the bait and instead wrote a deep dive on the pros and cons of being a lefty. Romantic for some, perhaps. By chance, my turn to write the company blog has come round near Valentine’s Day again, so this year I decided to write about something that almost everyone in the UK has developed an affection for at one point or another… biscuits! Whether you’re a diehard digestive dunker, a custard cream connoisseur or simply love a cheeky chocolate bourbon, we’ve all bonded with a biscuit at some point in our lives. As great as they make us feel, though, could there be something toxic about our relationship with biscuits?

Eating biscuits can be traced back all the way to Neolithic times,[1] but it was the Romans who fully embraced the true origins of biscuits. The name comes from the French term ‘biscuit’ (pronounced ‘bis-kwee’), which itself originates from the Latin phrase ‘panis biscotus’, which refers to bread twice-cooked. Romans certainly ate re-baked bread, a form of biscuit that’s now known as a rusk, and it was especially handy for travellers and soldiers’ rations since it kept for longer than plain bread. In the 14th century the definition of a biscuit began to broaden. Wafers, made of sweetened batter, were one of the longest lasting medieval biscuits, and were eaten at the end of a meal as a ‘digestive’. Original, savoury biscuits didn’t die out though. Ship’s biscuits, renowned for their inedibility, became a key part of naval provisions as sailors spent increasingly long stints at sea from the 16th century onwards.[2] By the 17th and 18th century, improved access to ingredients, new cooking technology and complementary goods (tea and coffee) led to a biscuit boom in Britain among the wealthier classes. Then, two industrial revolutions (first steam power, then electricity) resulted in mass-manufacturing that allowed biscuits to be enjoyed by everyone. Brits had to wait until the 20th century for the birth of modern classics such as the ‘iced gem’, the ‘pear’ (a precursor to the rich tea) and, my personal all-time favourite, the chocolate digestive.

The growing love affair of Brits with biccies hasn’t slowed down since. A Harris Interactive survey from 2019 concluded that over half of UK consumers bought biscuits at least once per week, with 15% of the 25-34 age group purchasing them daily. Crumbs. According to market analysts Kantar, biscuit sales in the UK grew by 11.2% in cash terms in 2024 to £3.6 billion. This represented a gigantic 2.87 billion packs, 86 million more than 2023, with the average price per pack up 7.8%.

All is not entirely rosy in biscuitland, however. A term first coined in 2009 by Carlos Monteiro, a professor of nutrition and public health, has reared its frightening head in recent years. ‘Ultra-processed food’ (UPF) [3] is a phrase that sends shivers down Big Biscuit’s crumbly choccy spine. Past research has linked UPFs to an increased risk of health conditions including obesity, heart disease and cancer. Unfortunately for biscuit savants, the circular treats are firm favourites up front in UPFs’ first 11.

And it gets worse. According to a new study published on February 2, UPFs have more in common with cigarettes than with fruit or vegetables. The report finds that there are similarities in the production processes of cigarettes and UPFs, particularly regarding manufacturers’ efforts to optimise the ‘doses’ of food products, and how rapidly they act on reward pathways in the body. The authors also argue that UPFs meet established benchmarks as to whether a substance should be considered addictive. I’m sure that many can relate to the siren song of a biscuit tin, drawing you in for just one more Jammy Dodger. What’s worse still is that biscuits and other UPFs can impact both physical and mental health. For example, the rapid absorption of sugar in biscuits can cause glucose spikes and crashes, which along with dopamine release often result in setting up a ‘reward’ loop in the brain, impairing focus and promoting cravings.

Despite our rich tapestry with the cookie, the negative externalities associated with UPF consumption are pretty hard to deny, mainly in the form of decreased productivity and an increased strain on public finances from higher sickness rates. Fortunately, new regulations are coming in to try to balance Britain’s unhealthy obsession with the discoid goodies and other less healthy foods. As of January 6, the UK has introduced new promotional and advertising restrictions for products high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS). This follows a ban on HFSS products appearing in volume promotions such as ‘buy one get one free’, which together should help to reduce overconsumption, especially by children, who are most at risk of biscuit overload. UPFs (not just biscuits) account for some 60% of an average UK citizen’s daily caloric intake (in Italy it is 20%). However, that share can come crumbling down with careful regulation, proper education and the promotion of healthy alternatives to UPFs.

Take Fathom for instance: when foraging for a sweet indulgence, my fellow Fathomites and I have an option of biscuits or fruit! If UPF guilt was only mildly pungent on a shivery winter’s day, one could even choose to select both: say, a banana and a chocolate hobnob. I’ve never personally done it, and I’m not sure the two wouldn’t cancel each other out, but as the saying goes, you do you. Enjoying a good biscuit here and there, to toast a mini victory or fuel a late night at the office, should never conjure up the same negative emotions analogous to smoking a cigarette inside, or drinking a pint for breakfast.

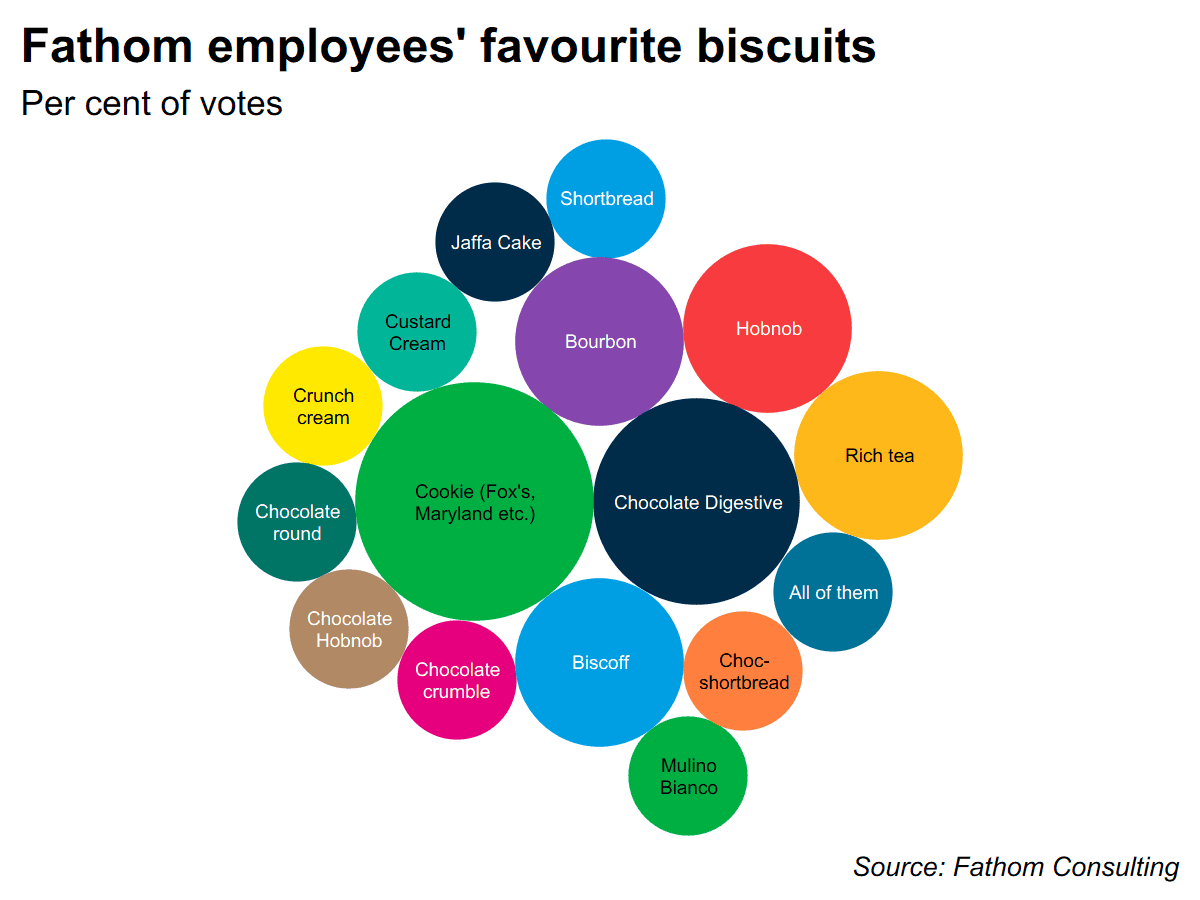

In my eyes, cutting out a long-standing tradition, one which has been around for thousands of years and most likely a part of Fathom since the company’s establishment, would be more than crude. What’s far more important is finding a healthy, balanced diet that minimises the number of UPFs[4] consumed per week rather than quitting biscuits for good and simply substituting them for a different demerit good. But that’s just my opinion. So, naturally, I had to survey the rest of Fathom to see what they thought. First up, what’s everyone’s favourite biscuit?

A sad result in my eyes. Cookies took four votes, pipping my lovely chocolate digestives to the crown. Next, what proportion of the company would be willing to part ways with biscuits in the office…

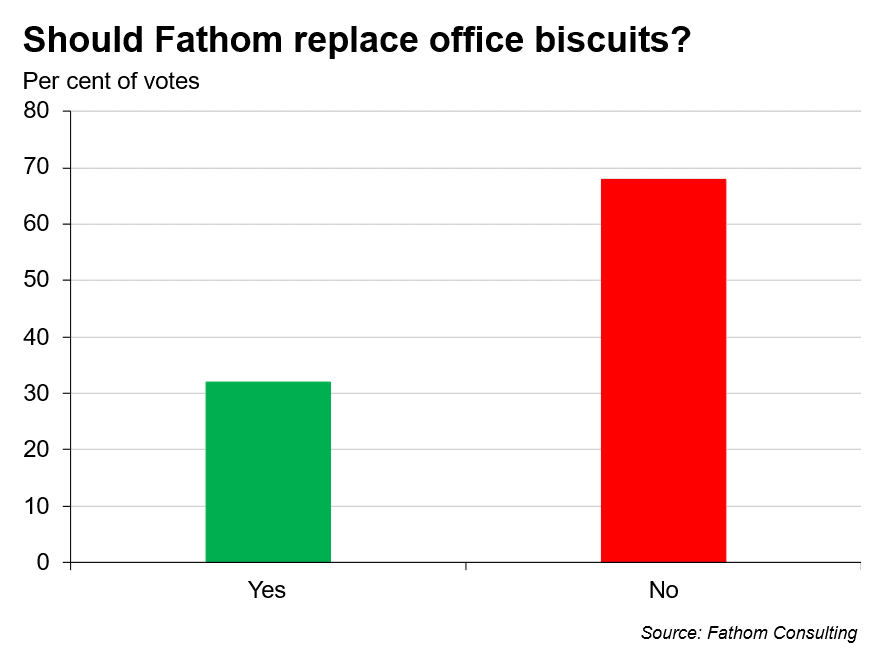

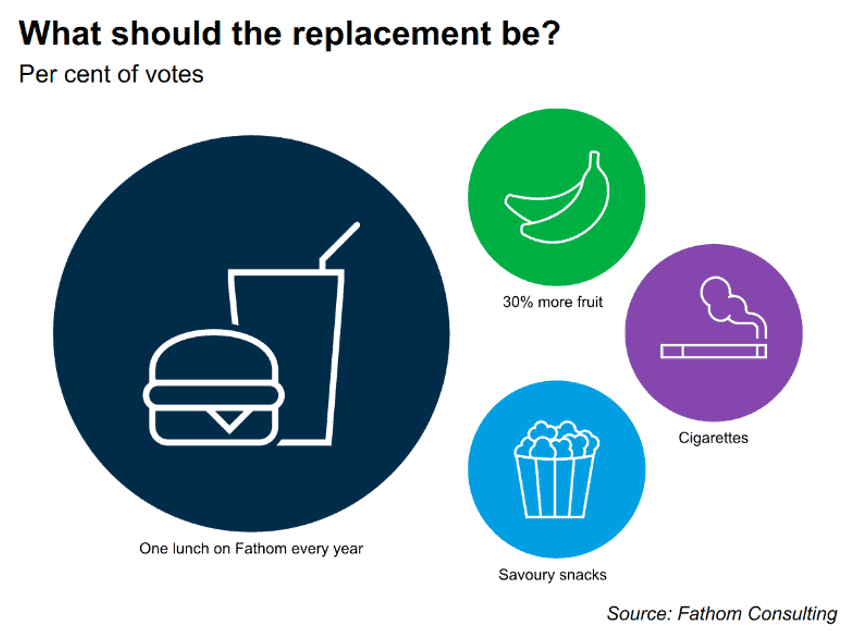

A more comforting result; over two thirds of the company selected no. Of the mutineers that voted for biscuit banishment, what would their ideal substitution be?

If you’re only just learning what ‘ultra-processed foods’ means, it may be worth re-appraising the snack cupboard. Regardless, the biscuit will most likely thrive on in British supermarkets, enticing consumers with its, albeit regulated, captivating packaging and intriguing new flavour profiles (white chocolate digestives are now a thing?!). However, overconsumption of UPFs can have incredibly adverse effects on human health, and in turn on the health of an economy. Being cognisant of their risks is no foolish way to live. Maybe only then can one settle down, purchase a 4-by-4 and share an everlasting, healthy, blossoming romance with biscuits! The end.

More by this author

Decarbonising Formula One… again

[1] Archaeological remains of cooked grains could be distinguished as porridges, cakes, or flat biscuits. They were most likely baked on stones.

[2] The earliest surviving example of a biscuit is from 1784; a ship’s biscuit used as a postcard! Ship’s biscuit | Royal Museums Greenwich

[3] UPFs are food products that have been industrially manufactured, comprising five or more ingredients which often include non-kitchen substances such as emulsifiers, preservatives, colorants and flavour enhancers.

[4] That’s not to say that all UPFs are created equal and therefore do not deserve a place in our diets. Indeed, people who follow a vegan, gluten-free or any other restrictive diet can find they depend on UPFs for a large proportion of their caloric intake. Minimising HFSS UPFs from one’s diet is a good place to start.