A sideways look at economics

A couple of weeks ago marked my tenth wedding anniversary, a day I have fond memories of as much for its watershed moment as for the partying. And party we did! It’s always a good sign when the bride, who had allegedly been actively waiting for this day for over ten years, only remembers about half of it. Or perhaps a tell-tale sign; the jury is still out. Against the odds, I still have vivid images of the day as do many of our friends who routinely bring up interesting anecdotes such as the jetlagged Australian friends who raised a few eyebrows among the guests by trying to keep awake and sharing a flask of whisky around…in church! Without wanting to detract from my wedding anniversary, today I’m writing about another tenth anniversary: my first microfinance loan.

The wedding and the microfinance loan anniversaries are actually linked and not just some twisted clickbaity way to grab the reader’s attention (assuming you care about my wedding, which would surprise me). It is customary at weddings for the bride and groom to give the departing guests a little gift. At the risk of sounding ungrateful, these gifts are generally an afterthought and tend to gather dust on a shelf before being either tossed away or offloaded to a charity shop (the same fate does not apply to the sugared almonds which are usually eagerly scoffed in seconds). Craving originality and breathing space from the stresses of organising the wedding, we decided to ditch this clichéd consumerist tradition and sprinkle the wedding with some neoliberal fairy dust instead. We transferred the wedding budget earmarked for the favours to Kiva, a US charity offering crowdfunded microfinance loans. Our guests were given a link and password (along with sugared almonds) and were invited to join us in making some loans. None of them ever did. However, I have continued to invest and reinvest these loans for the past ten years.

To be clear, there are no profits to be made, as users extend interest-free loans to Kiva which provides due diligence for its users and a large distribution network to many microfinance organisations around the world. My interest in this endeavour went beyond the wedding, it was both personal and professional.

I first came across microfinance through a friend during a stint working at UNCTAD (the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), in the early 00s. Those were the golden days of globalisation and neoliberal ideals. The theories were being lapped up with gusto and implemented with zeal. More importantly, they seemed to work even as they were already creating inner tensions and identity crises. It was fascinating, for example, to see an organisation like UNCTAD wrestling with the dilemma of how to make globalisation work for the poorest countries while also trying to break out from the shadow of the WTO, unquestionably the coolest kid at the time. (How things change!) Microfinance was a, small, part of that effort. For example, it’s a little-known fact that MIX Market, once the most comprehensive database on microfinance institutions, was first conceived by UNCTAD and then handed over to the better-funded World Bank to be maintained. You certainly wouldn’t guess this from reading a more recent, self-proclaimed ‘definitive book’ about the fall from grace of microfinance by some of the same people at UNCTAD.

Researching some of the content for this blog, I’ve been really surprised about this recent backlash against microfinance initiatives, even if it mostly originates from the same small group of loud voices. I won’t be dragged into a debate about the merits or demerits of microfinance, especially in an end-of-the-week blogpost. Suffice it to say that microfinance was always niche, despite some bold claims to the contrary. Fears and claims that it heralded a new dawn in development economics where market forces reigned supreme and public and international policies were going to be made redundant were wildly exaggerated. Microcredit was always a complement to classic development policies that, at the turn of the century, seemed to have lost sight of harnessing grass-roots incentives and overcoming bottom-up local constraints.

On a personal basis, listening to Mohammed Yunus speak was a revelation for a young mind that had been mainly excited by theoretical constructs up to that point. The idea behind microfinance is beautiful: teaming up borrowers to help overcome adverse selection is a simple, elegant and real solution to the problem of enabling access to credit and consumption-smoothing for those deemed unbankable by traditional institutions.

The patchy record of microcredit initiatives when it comes to poverty reduction efforts ought not to detract from recognising their influence in re-focusing attention on the local dimension of development programmes. Particularly as the development world is littered with efforts of questionable efficacy at the top-down level that still receive a lot of funding, and not enough scrutiny. As a cheap dig, it might be sufficient to remind readers how ‘Vision 2020’ stopped sounding like a smart marketing pun and got quietly dropped as a tag line for the still ubiquitous UN Millenium Development Goals.

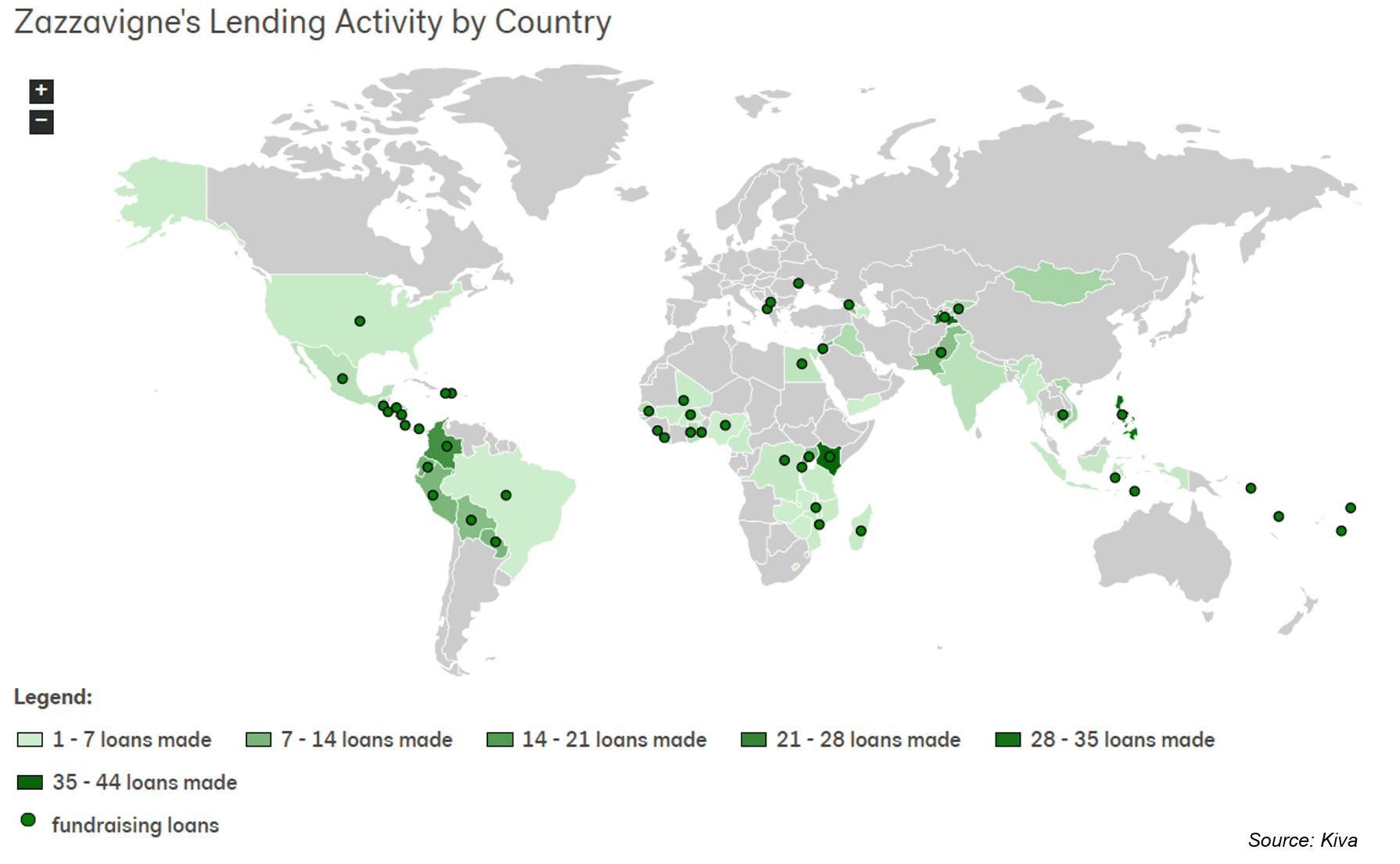

It’s also not very hard to find success stories within microfinance and Kiva is undoubtedly one of those. What sets Kiva apart from other platforms is its relatively low loss rate. Kiva claims a repayment rate of about 96%. This is outstanding, considering some of the loans are in the poorest, riskiest parts of the world often torn apart by war, natural disasters and instability. The claim is fully backed up by the performance of my portfolio. Out of the 534 funded loans in 63 different countries I made (typically at $25 a pop), I suffered defaults on 17. This amounts to an average default rate of very roughly 3.2% over the past ten years.

By comparison, the annual default rate on US credit cards has been 3.4% on average since May 2011 according to data from S&P and Experian. In terms of actual losses, after ten years, I still have $1144 of the original $1500 deposited. This implies another crudely calculated annual 2.7% loss rate.

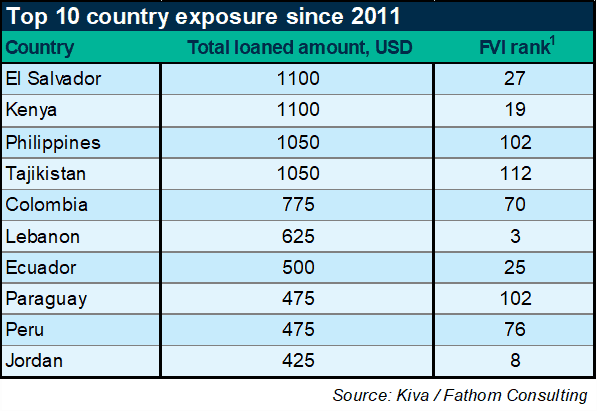

The table below shows the Top 10 countries to which I’ve had the greatest exposure and how risky the country is according to our proprietary measure of financial risk — Fathom’s Financial Vulnerability Index (FVI).[1]

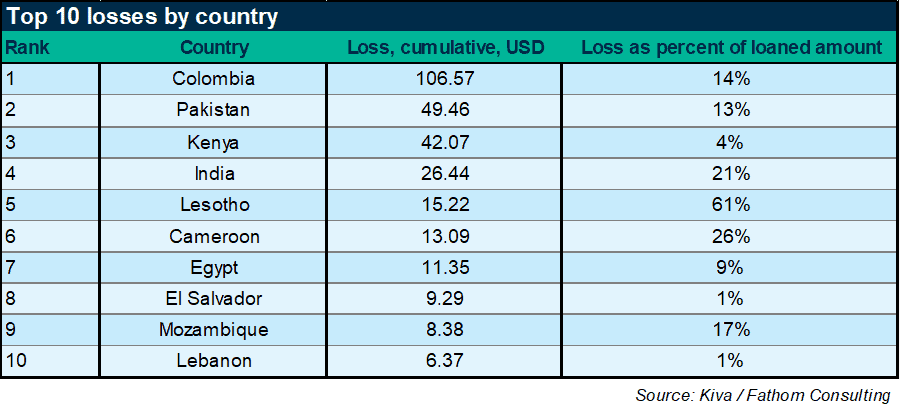

The next table shows the losses that I have suffered in absolute terms and as a share of the total loans pledged in that country:

Of the above, the entirety of the losses incurred in Egypt and Mozambique were due to currency movements rather than defaults (for example, Egypt devalued its currency by half in 2016). All the actual defaults came from ten field partners, about 7.5% of all the local microfinance institutions I had exposure to over the years. Three of these microcredit organisations are no longer active on Kiva and at least one appears likely to have involved fraudulent activities (the defaults from Pakistan).

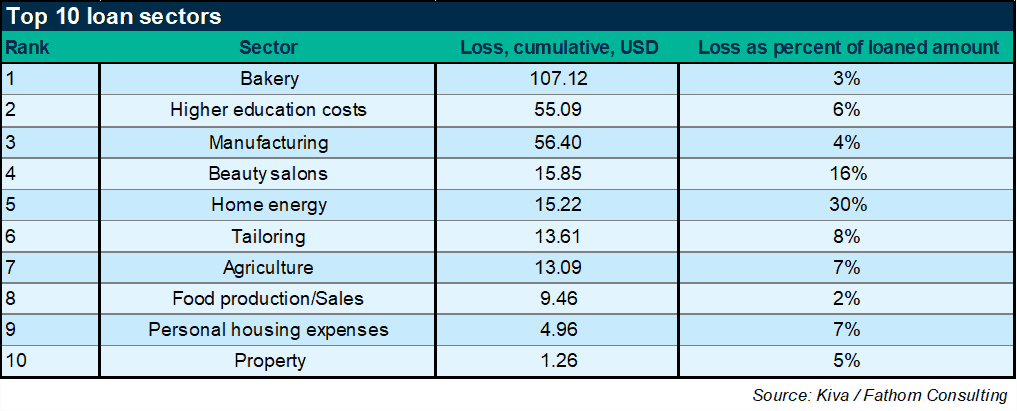

The sectoral breakdown reveals a clear preference for investing in bakeries and manufacturing sectors. On the former, the investment thesis is as refined and subtle as the sugar in some of the Middle Eastern sweets I’m extremely partial to and I have tended to support. On the latter, however, I am more prosaically trying to encourage high-value-added activities. The sectors with the largest share of losses relative to the invested amount were in beauty salons and home energy, two sectors that I am genuinely clueless about.

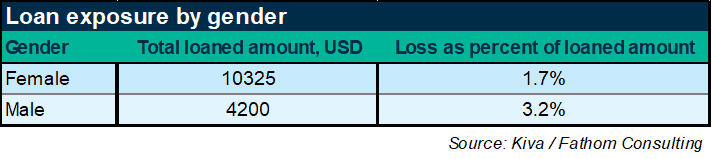

71% of the loans I made over the years have gone to women, a decision that paid off handsomely as they suffered significantly fewer losses than the loans to men as a share of the amount borrowed. This result is no fluke, as it’s a fairly well-established fact that women tend to be more risk-averse investors. It’s also worth reiterating that women in many poor countries greatly benefit from gaining access to finance as a gateway to winning their own voice and independence.

To conclude, ten years ago we promised our guests that their wedding favours would not be gathering dust and would be put to good use. Over this period, I have thoroughly enjoyed the process of crowdfunding loans on their behalf in no small part thanks to the brilliant work from the people at Kiva. I look forward to continuing this tradition as a regular reminder of that fantastic day ten years ago and of an interest in development economics that life choices have laid dormant, but that will never be forgotten.

[1] The FVI provides a probabilistic assessment of the likelihood that a country may experience a sovereign, currency or sovereign crisis. The FVI number in the table shows how a country ranks based on the highest probability across the three types of crisis considered. A rank of 1 signals the riskiest country.