A sideways look at economics

I have a confession: I used to be a gold bear. I was sceptical about gold’s soaring price around 15 years ago, when advanced economy central banks launched quantitative easing and gold rose to almost $2000. Investors were betting that this might cause inflation. I struggled to see the appeal of the yellow metal — it did not provide an income stream and was not much practical use to industry. It was challenging to value, and seemed mostly to appeal to permabears and hard money advocates such as Ron Paul. There was eventually a reckoning. As QE did not lead to runaway inflation, the price of an ounce of gold almost halved to just over $1000 by 2015. Job done? Not quite. The precious metal has since more than trebled, touching all-time highs in recent days. For investors managing today’s mix of risks, the asset class that glitters most may increasingly be gold.

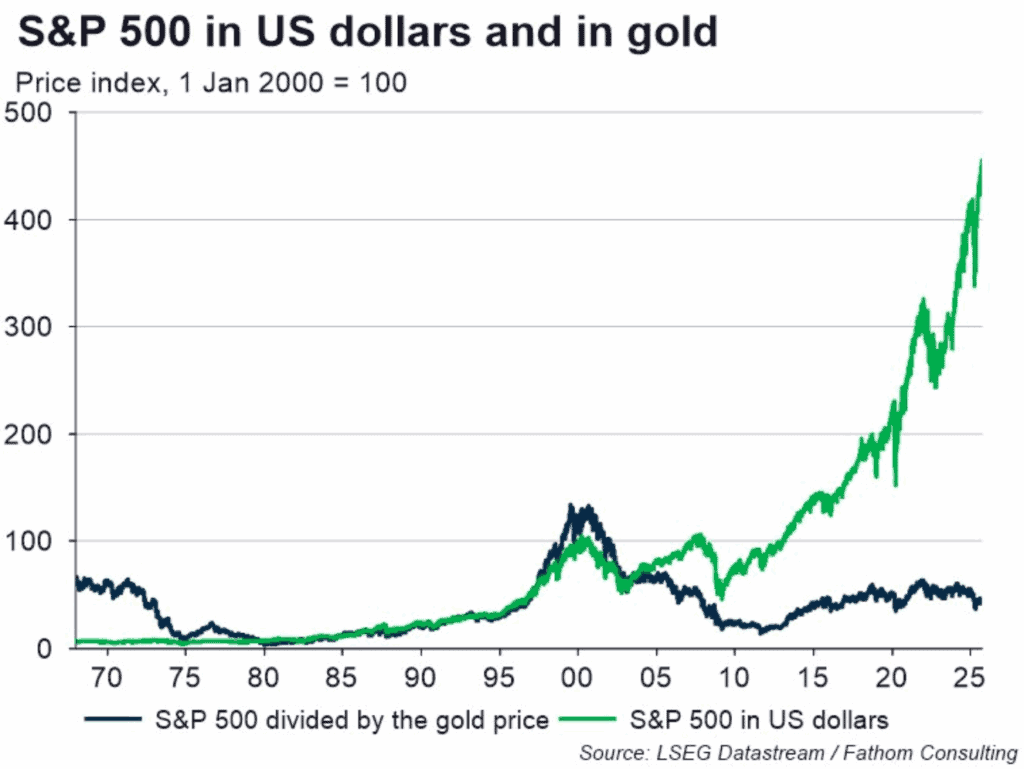

Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. But gold’s strong record should not be ignored either. Over the past 20 years it has returned more than 10% annualised for US dollar investors, helping it to outpace many major assets over that period. Indeed, Fathom rolled out a chart showing the S&P 500 priced in gold. When you do that, lofty valuations start to look a lot more normal.

One explanation is that investors are concerned about the purchasing power of traditional currencies. This has particularly risen to the fore after the post-COVID bout of inflation. There does seem to be a link between elevated price pressures and bullish sentiment for the precious metal. On average, gold has returned 1% in months when US inflation was above 5%, compared with 0.6% in months when inflation was below 2%. This implies that gold helps protect against inflation risks.

Acting as a temporary hedge against inflation is one thing, but could gold also now be benefiting from more substantial concerns about the public finances? G7 public debt ratios are near record highs, and there is seemingly little political appetite to do much about it. Without fiscal discipline, it is difficult to see a major decline in government debt burdens, absent an AI-driven boom in economic growth. I can see the appeal of gold in a world where traditional safe havens (advanced economy government debt) start to look risky.

A final and notable catalyst for gold is as a protection against potentially severe downside risks. Gold has played the role of a preserver of wealth for a long, long time. And this means that people turn to it when things are tough. The world is entering a new multipolar equilibrium that is bringing much heightened geopolitical tension. There is a major war in Europe, and countries are ramping up military spending. Conflict is rarely good for business. The fact that gold doesn’t produce an income starts to look more like a positive than a negative when potentially severe downside economic risks come into play. While gold may not boom in times of economic crisis, it tends to hold up more than equities. Meanwhile, conflict can be military or economic. For many emerging market central banks, keeping reserves in gold has started to look more appealing than keeping it in developed market government bonds that could be vulnerable to sanctions.

A backdrop of higher inflation, overindebted sovereigns and strained international relations all serve as positive catalysts for gold. Does this mean that bullion prices will continue to soar? In the short term, who knows? Markets sometimes appear to have a sense of irony, with articles like this a sign of a near-term tops. Often, the time to buy is when the bullish thesis is not immediately obvious — to the consensus, at least. On a longer time horizon, there seems to be a strong case for holding some gold. Historical returns have been good, and it should offer diversification benefits versus bonds and equities.

They say there is no one more rabid than a convert. In my case, conversion from gold bear to gold bug has not been as extreme. Fathom will be exploring the causes and consequences of high public debt ratios in the coming weeks and months.

More by this author