A sideways look at economics

A couple of weeks ago I found myself with a free day in New York. I did the usual touristy things — Empire State, Central Park, Broadway show… However, one thing in particular stuck with me — as I was walking along Seventh Avenue, I found myself confronted by not one but nine billboards, all advertising the new Superman film. Each was strapped to the side of the same building. Now, Times Square is famed for its excessive advertising, but this seemed to be taking things a little too far…

Before I go any further, I’ll acknowledge that I’m not a film industry expert. I also want to reassure readers that this week’s blog post will not include any spoilers for the recently released film, mainly because I haven’t actually seen it. Rather, this blog’s inspiration lies in that experience: standing there, looking up at the billboards and wondering why they were so keen to advertise Superman (it’s not like we don’t know who he is), and also why we are getting yet another Superman film.

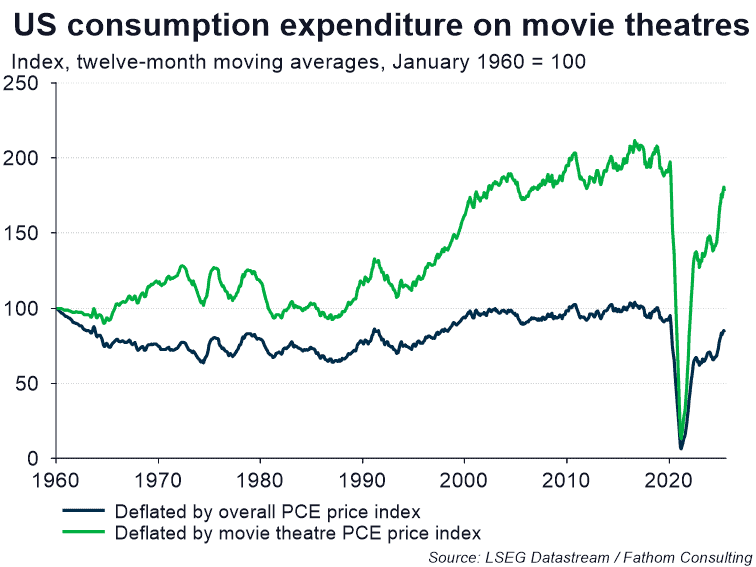

Turning to the first of these questions, I’m quite aware that marketing spends have escalated and are now a large part of the studios’ budgets. And I can see why — looking at the chart below, real US spending on attending movie theatres remains around 15% below both pre-COVID levels and the levels that were experienced in the early 1960s. Note here that I am quoting the numbers associated with the blue line below, where nominal spending is deflated by the overall US Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, which I view as a more appropriate deflator than the cost of a ticket (reflected by the green line below). Why? Because the former is more akin to how the film studios will evaluate their profitability.

As it turns out, the price of going to the pictures has risen by less than overall prices in the economy, suggesting that costs are being kept low in order to encourage more people through the door. This, coupled with the aggressive advertising that I witnessed, suggests to me that it’s increasingly hard to get people to go to movie theatres in the US.

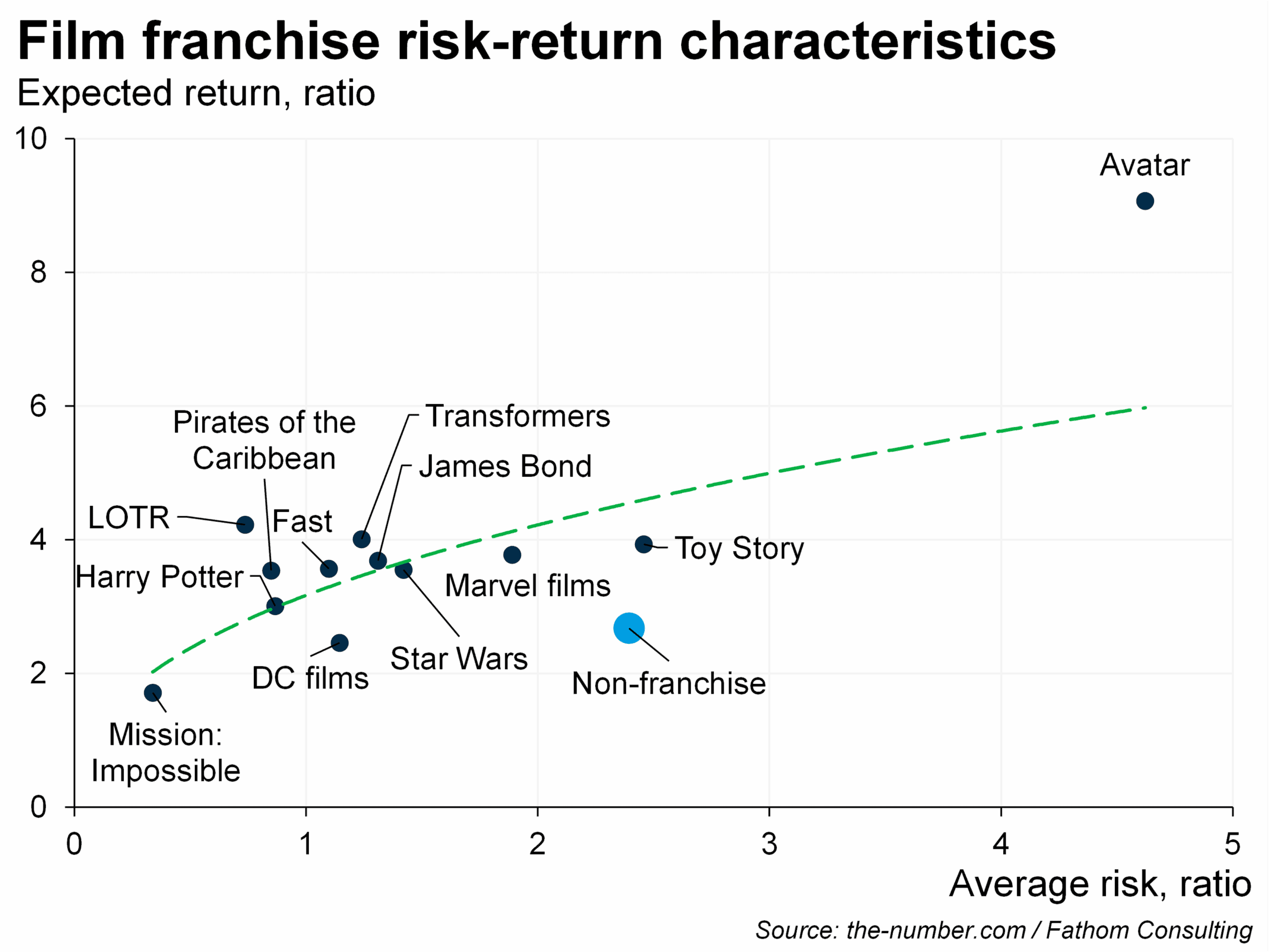

Turning to my second curiosity — why Superman again? — I have a suspicion that studios prefer the certainty in revenue that familiar franchises typically provide. As it turns out, there may be some evidence in support of this. The chart below shows one approach towards evaluating the risk-reward properties of film franchises, using data from the-numbers.com on the top 100 films by production budget.[1] As can be seen, risk generally rises with the expected return associated with the various film franchises shown below. This is probably to be expected. Non-franchised films tend to lie some way below the typical relationship indicated by the green-dashed line. From the chart, you can see that they offer greater uncertainty over their box office takings than DC films, but they provide no increase in expected return to compensate for this. Equally, they have the same degree of risk as the three Toy Story films in our sample but typically deliver a much lower rate of return. Looked through this lens, it seems like Hollywood’s pivot towards franchises appears highly rational.

So, I feel I understand why there’s another Superman film, and why Warner Bros is so keen to advertise it. While I’m not sure that I love the seemingly endless stream of franchised films, I can see why we’re in that world. What can we do about it? Well, as with anything, I guess the best thing you can do is vote with your feet — if you want more original films, go watch them at the cinema!

[1] My measure of profitability is perhaps controversial — I simply look at the ratio of global box office to film production budgets. This is done for simplicity and will ignore other factors such as the cost of marketing and revenues from related merchandise. Risk is defined by looking at the standard deviation of this return concept across the films associated with each franchise (limited only to the sample included within the chart). For the purposes of this chart, ‘non-franchised’ films includes all films that are in the top 100 films by production budget and either: a) not part of a franchise, or b) a part of a franchise, but only have one entry recorded in the top-100 budget list.

More by this author

A socially optimal dinner party