A sideways look at economics

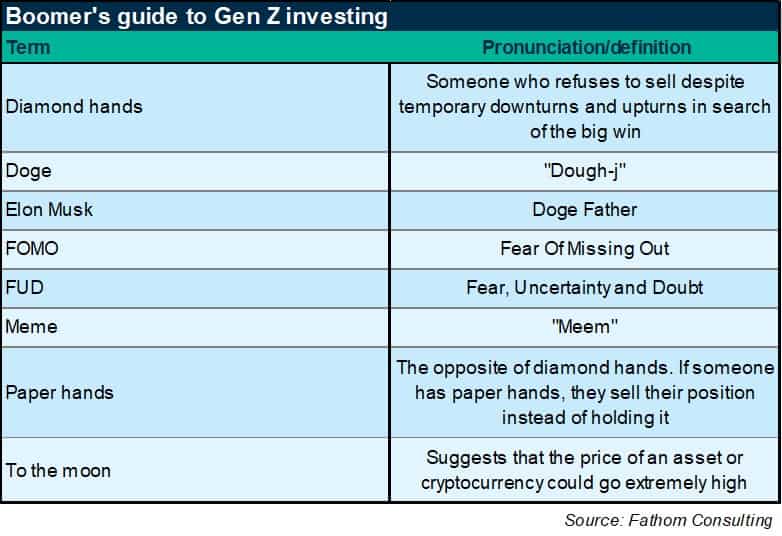

How many dogs have been to space? More than 20, if you’re interested.[1] During the 50s and 60s the Soviet Union sent numerous dogs into space, some of which never returned. Many investors will currently be hoping that Dogecoin (pronounced “dough-j”— you’re welcome, boomers), a meme coin (pronounced “meem”, no need to thank me twice), meets the same fate as the canine astronauts, and never returns from its sky-high price. (My impression of a general pile-in was confirmed when I recently overheard someone in the supermarket talking about investing in Dogecoin for their kids – it felt like a “the market has topped” moment.) This side story to the broad-based rise in crypto markets came to a head last weekend as Elon Musk, henceforth known as the “Doge Father”, was set to appear on the popular US late-night sketch show SNL, during which Dogecoin bulls expected the Doge Father to propel the meme coin’s price into the stratosphere. For those of us who have spent a little more time following markets, the adage “Buy the rumour, sell the news” came to mind. Sure enough, as Musk suggested in one of the SNL sketches “Yeah, it’s a hustle”, the market dropped more than 20%. Where were all those diamond hands?[2] This blog post will shamelessly hop on a trend and examine what economics can say about all of this.

There have been many attempts to model the fundamental value of cryptocurrencies. These include the quantity theory of money, comparing them to similar assets such as gold or money supply and examining network effects. To my mind, these valuation metrics are not particularly useful — yet, at least. The pressing question is not where the fundamental value currently lies but where the price will go in the coming weeks and months, and what determines that.

Keynes was among the first to explore how prices can be driven by factors other than the fundamental value of an asset. In his 1936 treatise A General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money he suggested that professional investment can be likened to a newspaper beauty contest, in which competitors must pick the six prettiest faces from one hundred photographs, with the prize being awarded to the individual whose preferences correspond most closely to the average.

The same idea has been applied in a scenario more analogous to financial markets. Richard Thaler published an experiment in the FT in which individuals must select a number between 0 and 100. The person closest to two-thirds of the average guess would win two business-class tickets to North America. How? Under Nash equilibrium everyone’s strategy would be to pick 0. Why? Because Nash equilibrium assumes that everyone knows everyone else’s strategy, and is picking their best response given that strategy. The only solution where no one has an incentive to change their strategy is when everyone selects zero. However, people do not tend to play the Nash equilibrium strategies in these types of games.

So, what strategies do people actually play in these games? Individuals are probably applying n-level thinking. Suppose the Nash equilibrium price for Dogecoin is zero. Our enigmatic Technical Director Andrea Zazzarelli, as a super-forecaster, realises this but does not believe that everyone else will. He then adjusts his expectations accordingly. He may instead believe that everyone else is naively optimistic about the price and will push it up. Based on this belief, he may decide it will be profitable to invest. Does this make him an irrational Barstool Sports reading, Infowars watching idiot? Not in my opinion (and that’s not just because he’s my boss).

This type of thinking was evident in the response to Thaler’s experiment, as the average guess was not zero. Despite conducting the experiment on a highly financially literate audience, many of whom would have been aware of the Nash equilibrium at zero, the average guess was 18.9. The most popular guesses were 33, 22 and 0/1.[3] This suggests that participants were using different levels of thinking when making their bids. Those who chose 33 probably concluded that if everyone else was selecting numbers at random the average would be 50, and the winning bid — two-thirds of the average — would be 33. Those who chose 22 likely concluded that if everyone else was a 1-level thinker, the average would be 33 and the winning bid 22. This same logic iterated infinitely gets us down to the Nash equilibrium of . With an average bid of 18.9, the winner was the individual closest to 13. This means the winning level of thinking was to be a 3-level thinker, assuming everyone else would bid 22.

The most interesting results from the FT experiment came from the comments individuals were able to submit with their bids. Many individuals had reasoned the Nash equilibrium, much like our Technical Director Andrea, but were aware that others would not choose the Nash equilibrium. Based on that, they revised their bids upwards to account for this. Conversely, there were individuals that naively chose the Nash equilibrium believing that everyone else would choose this equilibrium. In crypto markets, this is analogous to individuals believing that cryptocurrencies’ values will revert to zero. Perhaps that is the Nash equilibrium. But, in the short term at least, the bounded rationality of others will keep prices away from it.

While the bounded rationality of others can keep prices elevated, it would take a brave person to suggest that significant corrections will not occur in the future. However, timing these corrections appears very difficult. This mirrors our findings when creating our Financial Vulnerability Indicator (FVI). We tend to find that it is easy to show that a country is ‘vulnerable’ to some sort of correction from a build-up of excesses, like a large current account deficit or a large budget deficit, but it is much harder to pinpoint when that vulnerability will turn into a crisis. A significant innovation in our work was the use of ‘reversals’ better to call the exact timing of crises.

Bitcoin saw a correction in April, falling from above $63k to below $51k.[4] The initial trigger for the fall was unclear: it could have been the mooted Biden tax rises or the collapse of crypto exchanges in Turkey. However, it was interesting to see how the initial shock was propagated. It appeared that margin calls on highly leveraged futures positions in cryptocurrency markets may have helped perpetuate the initial shock, along with some paper hands.[5]

This can be seen as a warning sign for how volatile these markets can be. Jemima Kelly in the FT points out that this volatility can in part be explained by the small amount of circulating supply. She suggests that 63% of Bitcoin’s supply hasn’t been moved in the past year. Were these wallets to begin unloading some of their crypto, we could see corrections that could be compounded by some of the vulnerabilities inherent in the markets (sorry about the FUD![6]).

In the long term, the jury seems to be out. Cryptocurrencies seem like nice asymmetric bets, but investors should be conscious of the risk/reward trade-off. As we mentioned in a recent note, there are reasons why a small allocation to Bitcoin or similar cryptocurrencies may not be a terrible idea. But as far as the short-term price dynamics go, your guess is as good as mine. An interviewer recently asked Elon Musk: “Does is matter that Dogecoin was created as a joke?” He responded: “Dogecoin was invented as a joke, essentially to make fun of cryptocurrency… There is an argument that fate loves irony… the most ironic outcome [would be] that the currency that was invented as a joke becomes the real currency.” To which the interviewer responded, “To the moon!” And what could sum up the last few months more aptly than that?

[1] It’s difficult to find exact numbers and it was hard to justify spending an hour researching this, though it was tempting nonetheless

[2] Slang for someone who refuses to sell despite temporary down and upturns in search of the big win

[3] The FT game only allowed individuals to choose whole integers which means there are Nash equilibria at both 0 and 1

[4] Bitcoin also saw a large correction this week as Tesla announced they would no longer accept it due to environmental concerns about the energy intensity of mining the crypto

[5] The opposite of diamond hands

[6] FUD is an acronym for “Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt”