A sideways look at economics

In Tupac Shakur’s social justice battle cry, Changes, the late rapper criticised his government’s priorities: “instead of a war on poverty, they got a war on drugs, so the police can bother me”. More than twenty years after his death, the war on drugs — or poverty for that matter — is little closer to being won.[1]. Meanwhile, the American government has fired the opening salvo in a different kind of battle: one against existing trade arrangements.

Donald Trump is delivering on one of his key economic pledges: to get tough on trade with China. His administration has already imposed tariffs on around half of Chinese imports, and threatened duties on the whole lot. Meanwhile, restrictions on inward investment have also increased. While financial markets have mostly taken rising trade tensions in their stride, in the US at least, there have been warning signs elsewhere.

A September poll of global fund managers found that a trade war was seen as the biggest downside risk to the global economy for the fourth month running, although history suggests that the big risks flagged by fund managers signal good buying opportunities. Separately, almost two in three CEOs polled by Business Roundtable said that trade tensions would negatively affect hiring and investment decisions.

Anxious C-suite executives may console themselves by looking to the upcoming midterm elections as a way out. The party of the incumbent administration tends to do poorly. If Democrats ride a blue wave to power, they will surely oppose the President’s China policy and things will go back to normal, right? Not so fast.

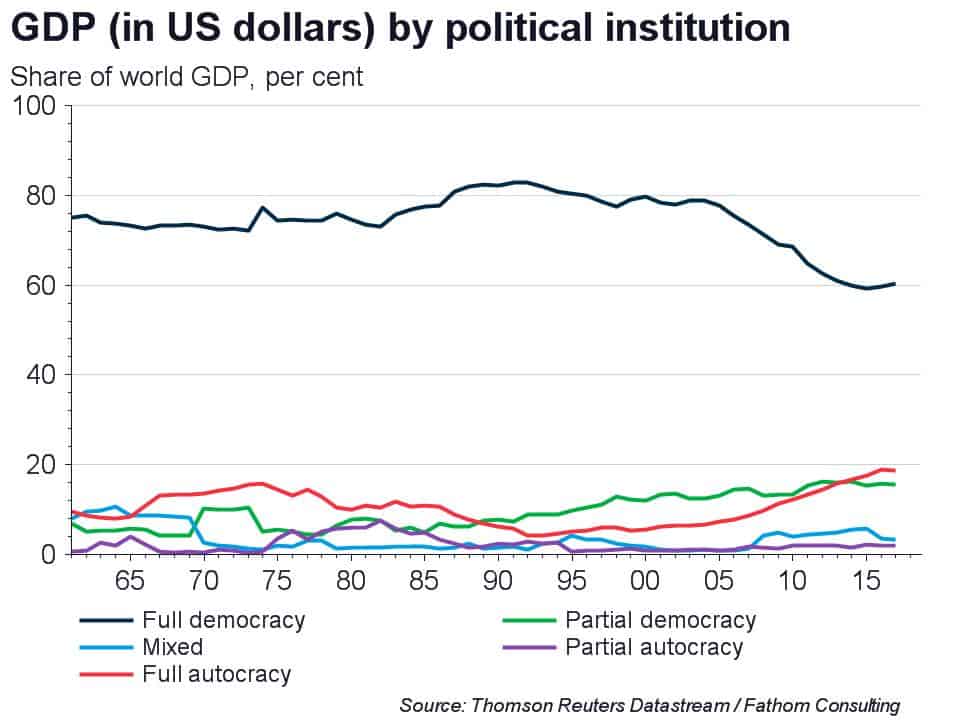

Since a 1991 post-war low of 4%, the share of global GDP accounted for by autocracies has increased almost fivefold, to 19%. Almost all of that can be attributed to China. There’s now more economic activity occurring under autocratic leadership than at the peak of Soviet power, when the US was engaged in a Cold War. Even under our own relatively bearish forecasts for Chinese growth, this share is set to rise for some time.

With WTO ascension, China was offered the chance to become more integrated with the rest of the global economy, in part based on the hope that membership would act as a moderating force. The reality is that the country got richer, without any meaningful change in its political setup. Now, after biding its time and hiding its capabilities, Beijing appears increasingly keen to export its political-economic model. Infrastructure signs in certain parts of Africa are more likely to have Chinese characters than “From the American People” written on them.

A city known to its residents for swampy summers and bad traffic, Washington DC is now associated around the world with bitter partisan divide. Amid the rancour, China may be a rare unifying force. On both sides of the aisle, from the right of the Republican party to left-wing Democrats, there’s a growing consensus that US policy towards the Middle Kingdom has been misguided. The status quo doesn’t seem politically palatable anymore. Economic skirmishes between the US and China may become the new normal, whichever party is in power.

It’s almost 50 years since Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs. Over that period, deaths by overdose have continued to increase. Current Sino–US tensions seem to reflect, in part, strategic competition — a national, not partisan concern. As with the struggle against illicit drug use, it’s unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. In a scene from The Wire, Ellis Carver, a member of Baltimore’s Drug Enforcement Unit, says: “You can’t call this…a war. Wars end”. A similar critique could be made about labelling current tensions a trade war. How about tradepolitik instead?

[1] Lyndon Johnson declared “unconditional war on poverty” in 1964, and had some initial success. However, the official poverty rate has seen no downward drift since the 1960s and remains stuck in double digits.