A sideways look at economics

Some readers will be familiar with our recent study on the economics of different ways to decarbonise aviation. One option we didn’t explore was not flying where an alternative mode of transport to get to your destination exists. My wife and I put this option to the test on this year’s family summer trip from London to Lithuania (where I am writing from now). With two kids. Ages 1 and 4. In an EV. Was it worth it?

I’d love to know what thoughts are going through readers’ minds right now. I’m guessing at a few, with my thoughts in response alongside.

This guy is crazy Agreed

Where is Lithuania? In the Baltics, near Russia – about 2,000km from London

That’s a cool road trip Yes

Does he still have a wife and two kids? I did this morning

Cool, but how long did that take? Six days

What? That’s insane. This guy is crazy Agreed

Where did he get all the time? One week of annual leave

Why? Reduce my carbon footprint, have a cool road trip and have my car at the destination, be able to take more things with me on holiday[1]

I’m pleased to report that the trip was a success: we made it to Lithuania without too many tears; no issues charging the car along the way; we spent two days at the Suntago Village near Warsaw, one of the biggest water parks in Europe, which the kids loved; we visited Berlin, a fascinating city, for the first time, where my one-year-old son was in his element. And we have our own car in Lithuania, meaning no car rentals or second-hand kids car seats. Happy days.

Realistically, we probably won’t drive to Lithuania every year, and in the interest of time, I will probably drive the car back myself and my wife and kids will fly (24 hours of driving in three days is not fair on the kids). But still, combined, we will have saved one ton of CO2 by not flying and had a cool family holiday and a new adventure.

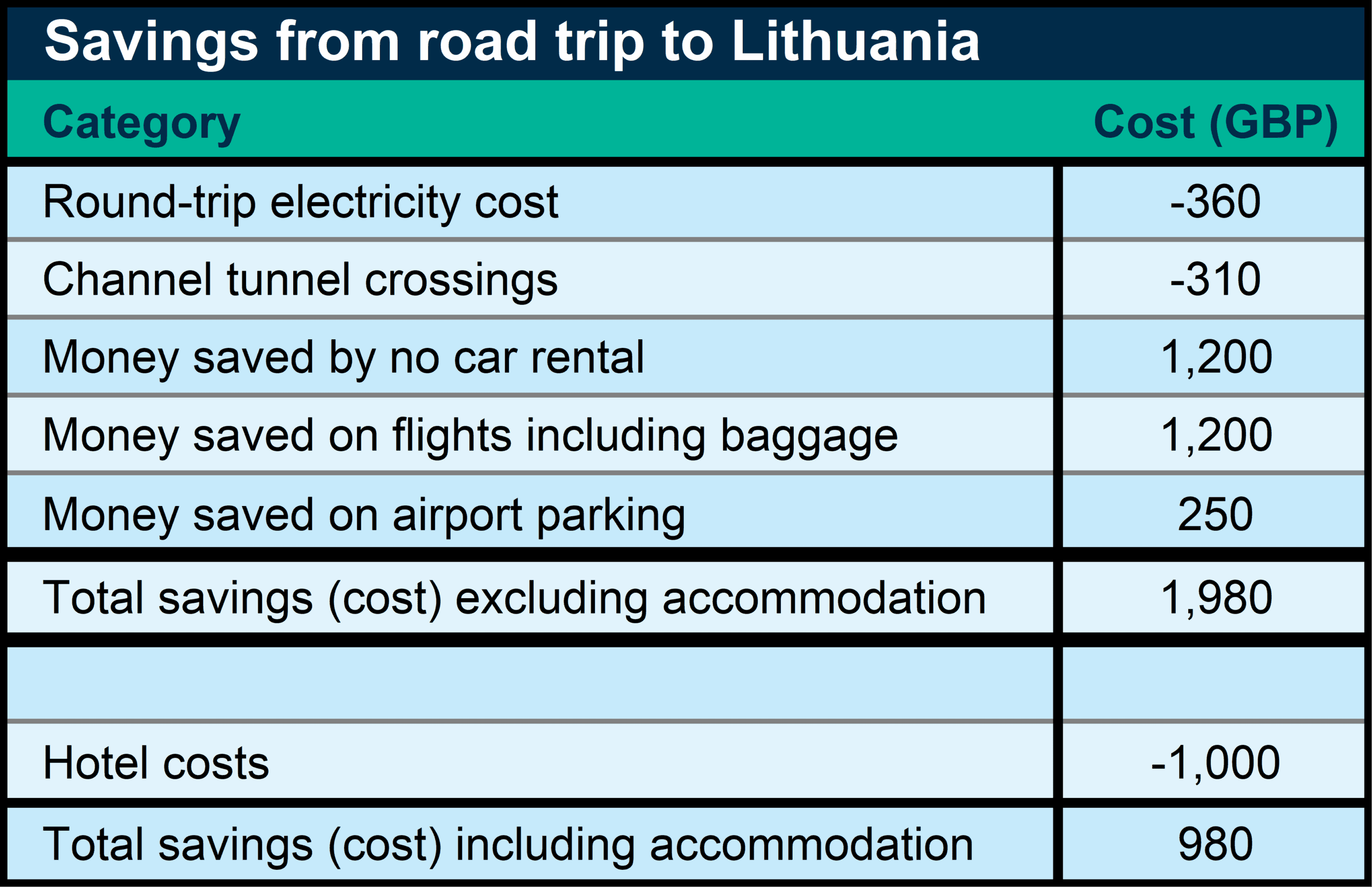

It turns out, given the price of flights and car rentals, you also save a lot of money by driving – not to mention the CO2 saving benefit. We save less, but still save, even if you count the cost of the hotels we stayed in along the way – yes, some of those were just stops for the night, to break up drives, but we also spent two nights each in Berlin and at a water park, which can go down as leisure, so we really shouldn’t treat those as transport costs (although I have in the table below).

The biggest cost is arguably the opportunity cost of the time it took us to get here. How much our time is worth is up for debate, but five extra days for two adults is a significant cost whatever way you look at it. But since in this instance the trip itself was the family holiday, we can ignore that opportunity cost and say that we saved nearly £2,000! Getting home may be a drag, but I am actually looking forward to three days on the road by myself, catching up on podcasts and listening to music.

This may not be everybody’s cup of tea, and driving here with the family probably wouldn’t be as fun next year, so my own calculations will change from year-to-year and the savings may not be as big. But the bottom line is that I did this to reduce my carbon footprint and I found a way to make the biggest opportunity cost of doing that an opportunity gain. Realistically, I won’t be able to drive to every holiday myself or sail to business trips across the Atlantic, which is why in our recent study we focused on the economics behind the different ways to decarbonise aviation (SAFs, e-kerosene and hydrogen) that don’t involve stopping flying. As we showed in the report, that might cost money, but it also creates economic opportunities, especially when it comes to hydrogen-powered flight. And, at the end of the day, we ought to keep in our minds what the world looks like in the future if we fail to decarbonise.

[1] Turns out that after packing snacks and toys for the trip, this was not in fact possible.

Access the report on decarbonising aviation referenced in this blog here

More by this author