A sideways look at economics

When Dutch traders began swapping tulip bulbs in the winter of 1636, they were not cultivating mania so much as cultivating a market — one that grew faster than the flowers themselves. A bloom that lasted only a few days each spring had become a collectible, prized for its symmetry and rarity. What followed has been described as mass delusion, but was rather a kind of social experiment in how value forms, and ultimately unravels, when enthusiasm becomes a currency of its own.

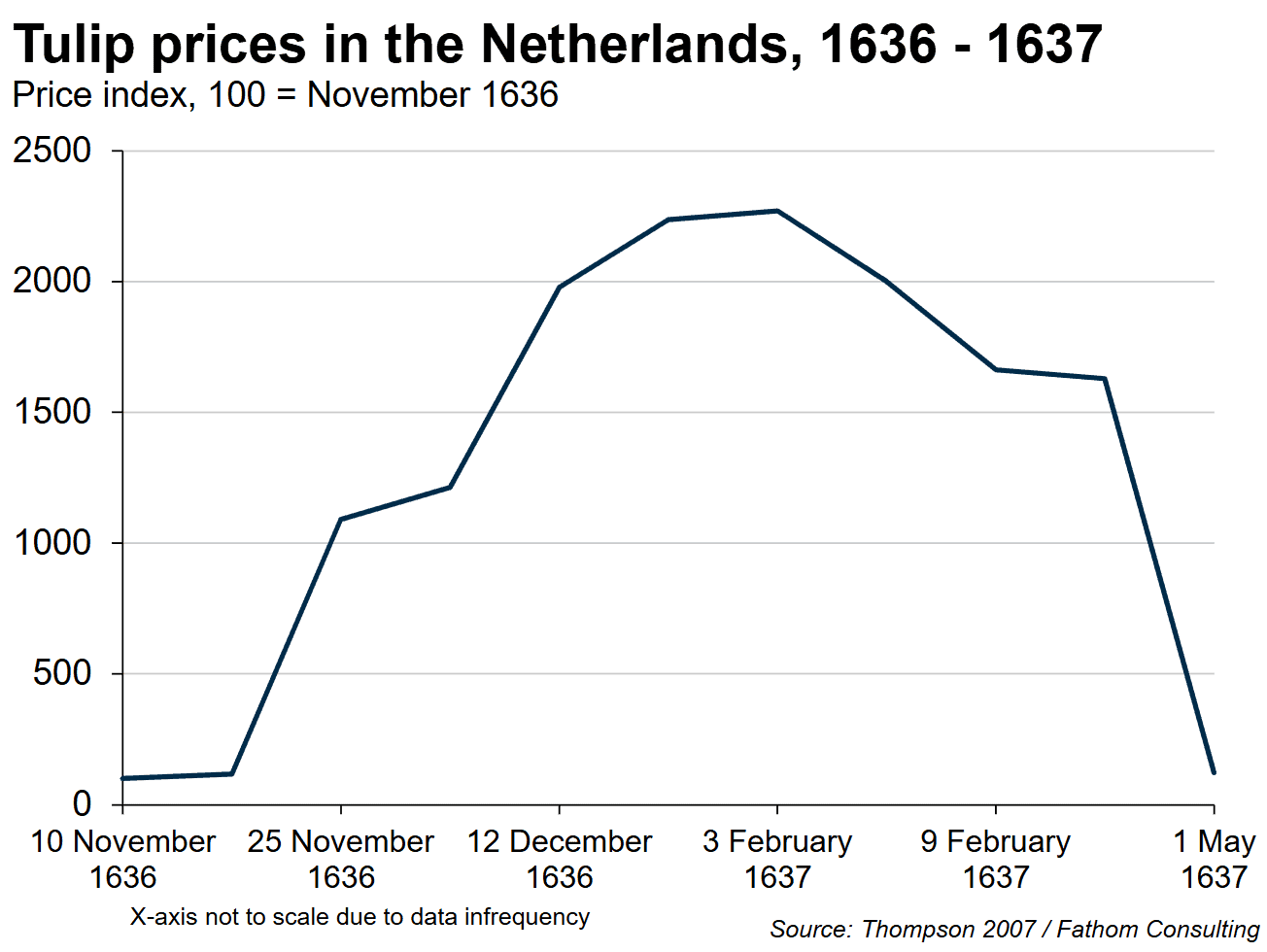

Prices for bulbs rose quietly through autumn before taking flight, soaring to 23 times their original price by the new year. Then, as quickly as the excitement had formed, it disappeared. The turning point came in early February 1637, when a routine Haarlem auction drew no bids. A few unpaid contracts circulated, confidence wavered, and the market froze. Much of the trade involved forward contracts — paper promises to buy or sell later. What had looked like liquidity was really leverage on belief — prices sustained by the hope someone else would pay more . When the authorities hinted these contracts might be unenforceable, the game was up. Within weeks, prices collapsed back to where they had started.[1]

This seemed extraordinary but tulips are not unique. The pattern is now a familiar one and reveals something permanent about financial psychology. A market sustained by the expectation of resale is a market sustained by conversation. Once that conversation stops, the floor disappears. The Dutch Republic, with its printing presses, merchant capital, and risk-taking culture, was simply the first society to discover that information could be traded.

Four centuries later, the same dynamic plays out on a grander stage. The chatter that once drifted along Amsterdam’s canals now hums across digital channels. The tavern table has been replaced by the online forum, and the speculative conversation has migrated to the internet’s trading floors — from Haarlem to Reddit, X, and Discord, to the endless scroll of Meta’s feeds and Google search trends. There, discussion of artificial intelligence now fills the role once played by tulip catalogues. The story begins, again, with genuine discovery — in the seventeenth century, the sudden appearance of vividly ‘broken’ tulips unlike any seen before; today, the emergence of machines that seem to reason, create, and converse. In both cases, novelty outpaced understanding, and fascination soon became a market..

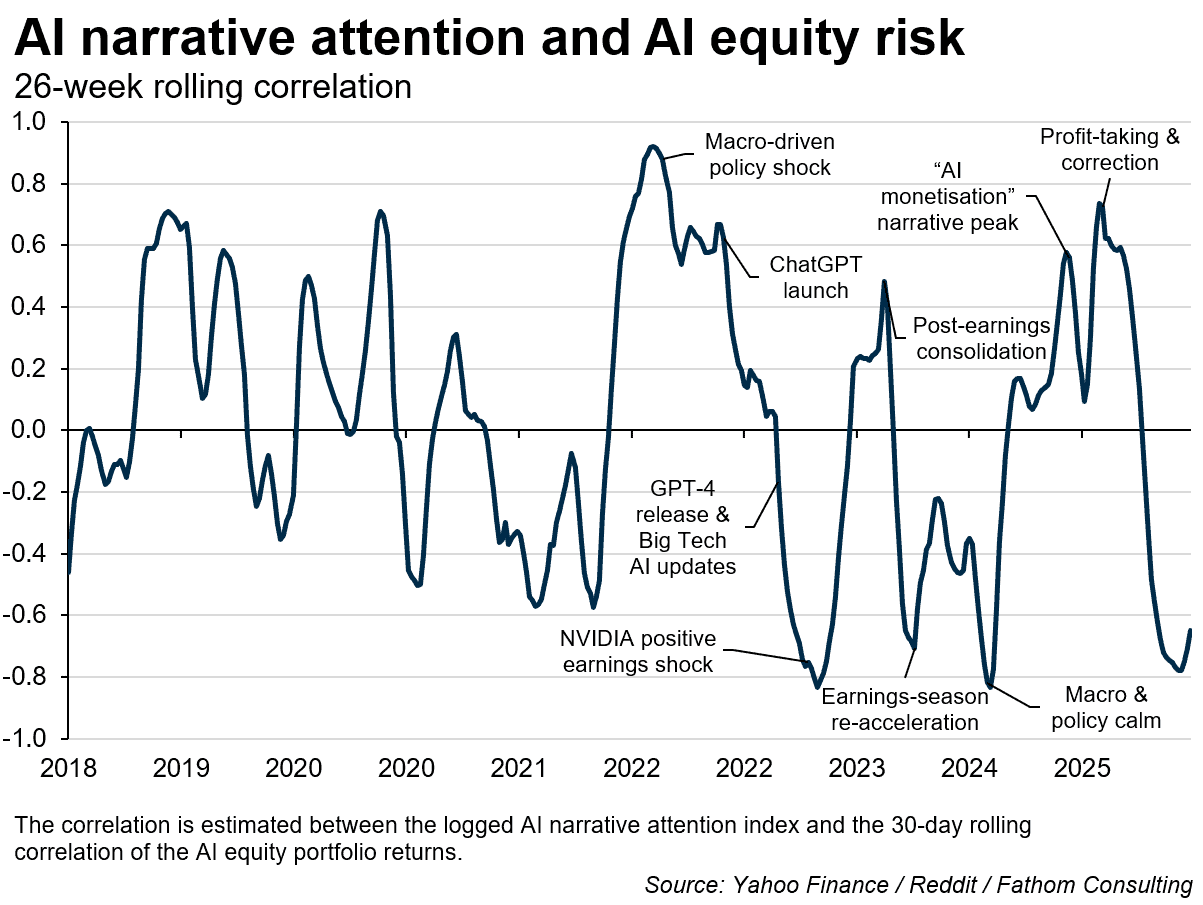

The modern parallel has unfolded less as a single crescendo than as one sustained over three acts. Prices moved first:[2] from early 2022, AI-exposed equities began to climb as firms channelled investment into chips, cloud infrastructure, and machine learning. This soon began to command attention.[3] From mid-2022, the online conversation began to build around “AI”, “ChatGPT”, and related terms — unevenly at first, with a few hiccups, then gathering pace through 2023 before rising almost vertically from late 2024 into this autumn. The two series now move almost in unison. Their correlation, barely 0.1 before 2022, climbs to 0.76 thereafter — suggesting that narrative and valuation have gradually learned to move together. Each new swell of attention lifts returns, but it also amplifies volatility.

Volatility can be seen to focus around narrative turning points. The past three years offer several: the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, NVIDIA’s earnings shock in May 2023, and the renewed ‘AI monetisation’ wave in early 2025 all produced clear volatility clusters in the data. Yet these bursts were intermittent. Attention continued to climb even as realised risk subsided through much of 2024, showing that enthusiasm alone does not sustain market nervousness. Both the seventeenth-century merchant and the twenty-first-century investor are still trying to price great prospects. Belief moves faster than evidence, and the ability to sell quickly at top prices — that is, liquidity — often looks strongest just before it vanishes. What differs is that today’s narratives are measurable. Where Dutch pamphlets once recorded gossip, we can now count it — every post, every mention, every surge of curiosity that turns into capital flow.

Attention, in this sense, has become a financial variable in its own right. When it swells, prices rarely stand still; when it fades, the market corrects. Volatility, however, responds in bursts: it flares with new information and then subsides, even when attention remains elevated. As participation widens, the range of beliefs broadens, and prices oscillate more readily at those moments — but attention alone is a poor proxy for day-to-day risk. It is better read as a regime signal for crowding than as a continuous volatility gauge.

That interplay between attention, price, and volatility is what links tulips to technology. Both moments follow the same cycle of narrative formation — discovery, diffusion, saturation, and correction. The details — bulbs versus chips, taverns versus message boards — are incidental. What matters is how investors behave when a story gathers momentum. In the Dutch Republic, that momentum lasted barely twelve weeks; in AI, it has persisted for more than two years. Yet the behavioural loop is familiar: novelty breeds attention, attention breeds volatility, and volatility breeds new narratives.

None of this means today’s enthusiasm is misplaced. Tulipmania is remembered as a parable of excess, but it also marked an early stage of financial sophistication. Forward contracts, secondary markets, and proto-derivatives flourished in its wake. Likewise, the AI boom is funding infrastructure that will outlast its own narrative — data centres, silicon capacity, algorithmic expertise. Bubbles, at their most constructive, are the R&D budgets of history: wasteful in the moment, indispensable in retrospect.

Still, momentum is not inevitability. The danger is less that AI will disappoint than that expectations will forget to pace themselves. When every company claims an “AI strategy”, surprise becomes scarce; when valuations hinge more on the number of mentions than on projected cashflows, markets drift from analysis to affirmation. The tulip traders knew that sensation well — they too mistook popularity for liquidity, until the music stopped.

History suggests such lapses are not new. Progress and folly have always shared a stage, each generation convinced that its boom is different. The Dutch thought they were creating a new asset class; we believe we are witnessing a new industrial revolution. Both are partly right. Human nature ensures that even transformative technologies follow familiar behavioural paths — we celebrate innovation by briefly overpaying for it, and only later remember the limits of conviction.

Yet from the wreckage of every enthusiasm something lasting remains. When the flowers lost their mystique, the instruments they inspired endured. From that brief mania came futures contracts, insurance, and the first cross-border clearing systems — one of the foundations of modern finance. If history rhymes, our AI moment may leave something similar: better models, better data, and perhaps better questions. Markets, after all, are conversations. The subject changes, the medium evolves, but the impulse to trade stories for prices endures. When talk turns entirely to innovation, it is worth recalling that attention is finite — and that volatility is its natural by-product. Somewhere between exuberance and scepticism lies the productive middle ground, where imagination funds invention before experience takes over.

The tulip may have withered, but its lesson endures: every great innovation begins as a fragile idea that someone is willing to overpay for. So let us keep an eye on the data, a sense of humour about our excitement, and a touch of humility when markets start sounding like poetry. Progress may not be linear, but it does have excellent narrative arcs — and, if nothing else, it gives us material for a good Friday .

More by this author

Built to last, struggling to change

[1] The tulip price index is taken from Thompson (2007), “The Tulipmania: Fact or Artifact?”, Public Choice, 130(1–2), pp. 99–114.

[2] Our AI equity portfolio is an equal-weighted basket of ten AI-exposed US equities and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETF) and Trusts — Nvidia, Advanced Micro Devices, Broadcom, Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta Platforms, Amazon, VanEck Semiconductor ETF, iShares Semiconductor ETF, and the Invesco QQQ Trust. Prices are converted to weekly frequency using Friday closes; returns are computed as week-on-week percentage changes, and realised volatility is estimated from daily returns using a 30-day rolling window.

[3] We develop an index that captures the intensity of online narrative attention surrounding artificial intelligence. Our AI attention index is constructed from weekly mentions of key AI-related terms across Reddit discussion threads. Mentions are aggregated across all topics, averaged into a single weekly series, linearly interpolated to fill gaps, smoothed using a multi-week rolling mean, and rebased to 100 at the first valid observation.