A sideways look at economics

The UK will leave the European Union later today, bringing an end to years of acrimony, confusion and inflamed passions. It could make a good topic for today’s blog post, but instead, I opt for something much easier and less emotive: debunking some of the fundamental beliefs underpinning capitalism. Controversial, perhaps, but the assumptions that humans are rational, and are driven by a desire to maximise income and consumption have been disproven by various studies, which have been praised by economists and are now widely accepted. Curiously though, when we think about problems, economists tend to ignore these studies. This is a problem. The solution isn’t simple, but a good starting point would be to develop a new narrative to describe homo economicus.

It’s not always easy being a macro economist: we need to explain the world, how it works, and why GDP growth is X% and what it’s likely to be in future. With a nearly infinite number of things that can affect economic outcomes, isolating the effects of one is tricky, never mind trying to understand how things affect other things and how those other things affect the economy. And then, we’ve got to predict what will happen. We can’t run ‘tests’ like a scientist would do in a lab, so, to do our job, we rely on incomplete sets of data, uncertain models, and a series of assumptions to help simplify those models. And rightly so. Simplicity is good, but not so good when the underlying assumptions are wrong.

It is not very hard to debunk the notion that humans are rational: some of us smoke, drink too much,[1] watch our favourite football team lose every week, we eat unhealthy foods and procrastinate. We know these things aren’t good, yet we still do them. We also do ‘good’, but irrational, things like setting ourselves random sporting challenges, like doing a marathon or swimming around the Scilly Isles, which, let’s be honest, sucks and requires hours of boring training. Some people take irrationality to extremes, like Alex Honnold, who climbed El Capitan with no ropes. In Russia, they have face-slapping competitions. Economists have some rock and roll examples too, such as the irrationality of buying lottery tickets or that we are massively underweight equities in our retirement portfolios.

There is also a lot of evidence that humans are not driven primarily by wealth accumulation. Yes, money gives us the ability to do more things, but what drives most people, I would say, is doing something you enjoy, feeling that you’re maximising your potential, being accepted by peers and sharing emotions and positive experiences with others. Being a part of something can have massive benefits and good vibes. Even the most successful individuals, including sportspeople, businesspeople and artists are not driven by money, but by an inner desire to be the best that they can be and to get recognition and respect.

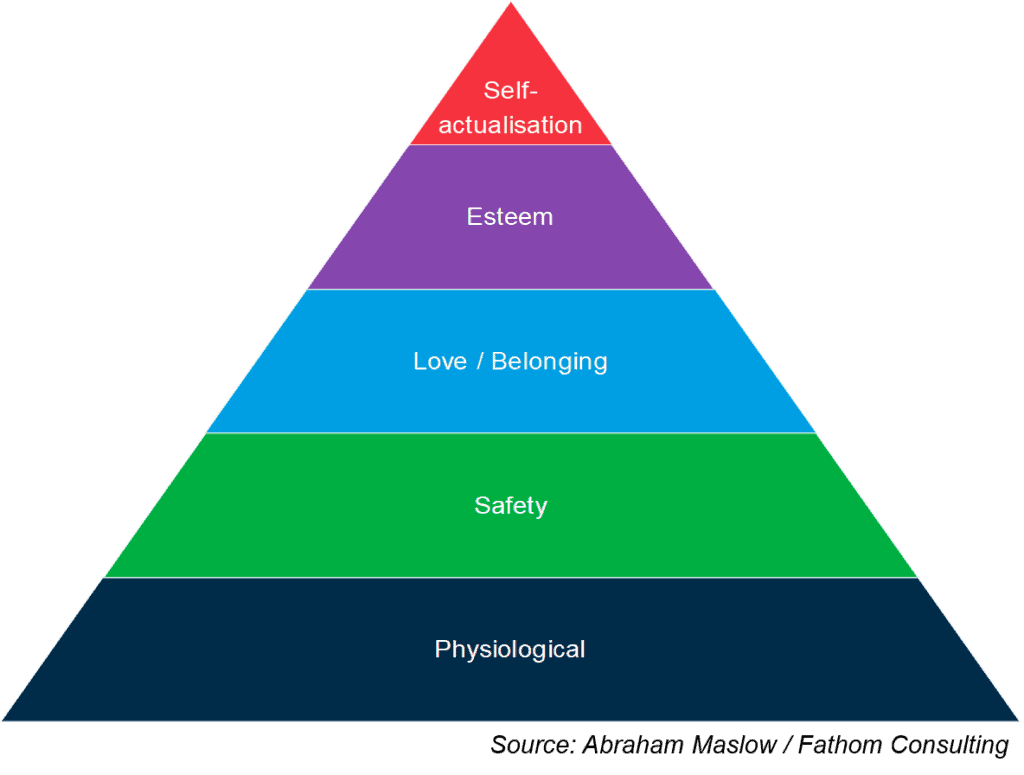

The seminal paper by Abraham Maslow in 1943 outlined how we have a hierarchy of needs, which can be represented by a pyramid showing needs in order of importance. A certain level of income is required to meet the most important, basic, needs at the bottom of the pyramid, such as being able to afford food and shelter. But money can’t buy love/belonging, esteem or self-actualisation. Another important point worth remembering is that some of the best things in life are free.

Mainstream microeconomics recognises that humans get utility from things other than money — there’s an extensive literature on the trade-off between working (to get more cash) and not working to have more leisure time.[2] Macroeconomists know this, yet still treat people as income-maximising, use income as a proxy for utility and GDP as a measure of prosperity.

The reason is because income and GDP are measurable and convenient yardsticks. There may be a strong correlation between income and prosperity and happiness, but they aren’t the same thing. And correlation doesn’t imply causation. It’s far harder to measure things like how much love and belonging, or how self-actualised someone feels. The macroeconomist’s approach to doing this would be to try and put a monetary value on how much we value those things. But in many cases, they can’t, and shouldn’t, be valued in monetary terms. Perhaps it’s impossible.

Another reason economists frame things in this way, I believe, is due to the prevailing narrative that we are this way, even if studies have shown this not to be true. Framing the big questions in the context of GDP and income often misses the big picture and won’t lead to the best social outcomes. Climate change is a good example. Economist William Nordhaus won a Nobel prize for his work in framing the climate change question as a monetary trade-off between the cost of making changes now, and the cost of doing nothing but having negative contributions to GDP from a changing climate in the future; this then boils down to how much we value the future over the present and technical things like discount rates. This is an important contribution, and the best within the current framework.

But the framework needs to be rethought. It’s important to recognise that people value the environment for reasons other than its effect on GDP. Many questions get framed this way such as tax policy, and minimum wage decisions. The notion that the incentive to work is seriously affected by tinkering with tax rates has always made me laugh. Remainers thought that framing the Brexit decision in GDP terms, and that Brexit would probably result in lower GDP, would scare people into voting remain. The outcome of the referendum, and subsequent surveys, have shown that many people cared about intangible factors more than GDP.[3] This is an example of how the population can be misread when thinking in these terms and how policy mistakes can happen (at least from the Remainers point of view).

Robert Shiller won a Nobel prize for his work in which he outlined how narratives can take hold, and how these have real economic outcomes. It is time for the narrative that homo economicus is rational, selfish and driven by money to be consigned to the bin. I am not rational. I am not always selfish. And I am not primarily driven by making money. Most people I know are like me. A new narrative, which recognises that we care about each other, and the environment, would be more helpful for setting policy. And for those reading this who manage money, there are practical implications too. More and more people investing their money want the custodians of that cash to consider ESG issues, and not just profit maximisation. Also, recognising that humans aren’t always rational, or have income-maximisation at heart, can help to better understand human behaviour. Ironically, this could also help you to make more money.

Capitalism and individualism are great. But the world has become divided, and polarised, and some improvements are needed. We ought to escape the shackles of thinking about everything in monetary terms. It’s time for a new narrative which recognises the value of collaboration, and the intangible benefits of being considerate over self-interest and monetary gain. I think the majority of us could agree on this. Perhaps that should be put to a referendum.

[1] It was pointed out to me by a friend that it could in fact be perfectly rational to drink too much, even knowing the health risks. For example, author, chain smoker and hard drinker Christopher Hitchens, facing death aged 62, didn’t regret his unhealthy lifestyle: “I burned the candle at both ends and it gave a lovely light”. Similarly, footballer George Best explained: “I spent a lot of money on booze, birds and fast cars. The rest I just squandered.”

[2] See previous TFIFs for more info: https://www.fathom-consulting.com/is-there-such-a-thing-as-too-much-leave/ or https://www.fathom-consulting.com/thank-fathom-friday-less/

[3] Personally, I happen to disagree with many of those reasons for leave, but I do recognise that it was not simply a monetary decision