A sideways look at economics

Now over halfway through my first year of full-time employment, detached from the education system, fully embracing those three certainties in life, the month of May has taken on a whole new meaning to me. Long gone are the days of pre-examination anxiety that plagued me for over a decade, and warmly welcomed is a commodity of indisputable value, a concept so important it stretches back to 1871. The bank holiday. As a treat for all those years of hard study, Andrew Bailey has decided to hold 2025’s ‘May Day’ on my birthday! Great man. However, this whole affair has got me thinking… Should more people be allowed a chance to celebrate their birthdays on a bank holiday?

Okay, so bank holidays aren’t actually determined by the Bank of England, but I’m certain Mr Bailey will be thinking of me on my special day. Believe it or not, a bank holiday has fallen on my 2nd, 7th and 13th birthday, three untamed days of inconceivable frivolity that I simply cannot divulge in this TFiF. As mentioned above, the May Day celebration dates back to Celtic times[1] and is traditionally associated with dancing ribbons around a Maypole as well as crowning someone the ‘May Queen’. Heavy my head shall be. The UK[2] has eight bank holidays a year: five of them being non-religious, on top of three over the Christmas and Easter periods. However, some readers might be shocked to discover that this is on the lower side of the global distribution of national holidays. Only Vietnam, the Netherlands and the USA[3] have fewer government-approved days off, while India has the most annual public holidays, ranging from 35 to 42 depending on the state and workplace. Of the G7, Japan tops the list with 16 days of public holidays, followed by France, Italy and Germany, with the European average at around 11. While this ranking does not account for the inter-country variation in paid annual leave quotas, can an economic argument be made to increase the UK’s measly tally of bank holidays?

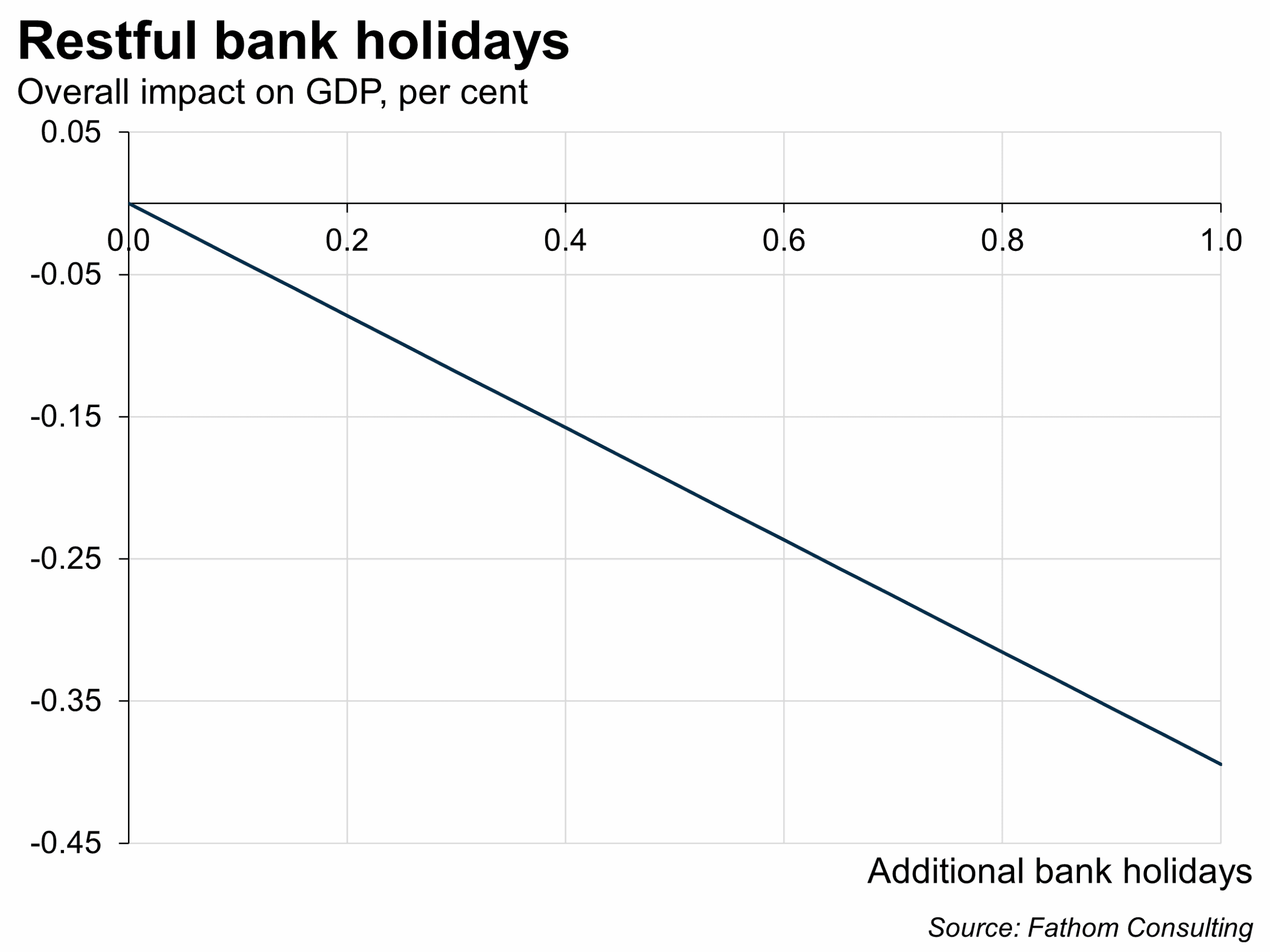

Let’s suppose the end goal of raising the number of bank holidays per year is to maximise UK Gross Domestic Product (GDP). To keep this model simple, we shall assume that Homo Britonomicus can only participate in two types of activities during a bank holiday. ‘Rest’ or ‘leisure’. ‘Rest’, in the short term, should reduce GDP. People who take time out from production to sit at home doing next to nothing will contribute little if anything to the economy during their day off. However, in the long term,[4] many studies suggest that rest is essential to maintain or even enhance productivity, which in turn boosts GDP. (Rosekind, 2010) (Dababneh, 2001) (Henning, 1997). At this point, readers may be postulating to all those around them that ‘leisure’ can itself often be considered a form of rest. However, on a bank holiday, with the sun gleaming down and any notion of work dispelled from the cerebrum, Homo Britonomicus enjoys something a little different to the traditional economic definition of leisure. Though the UK’s GDP growth and productivity has been lacklustre for over a decade, in real and nominal PDPP (pints drunk per person) terms, the UK outperforms plenty of countries around the world, ranking 8th in total beer consumption over 2023.

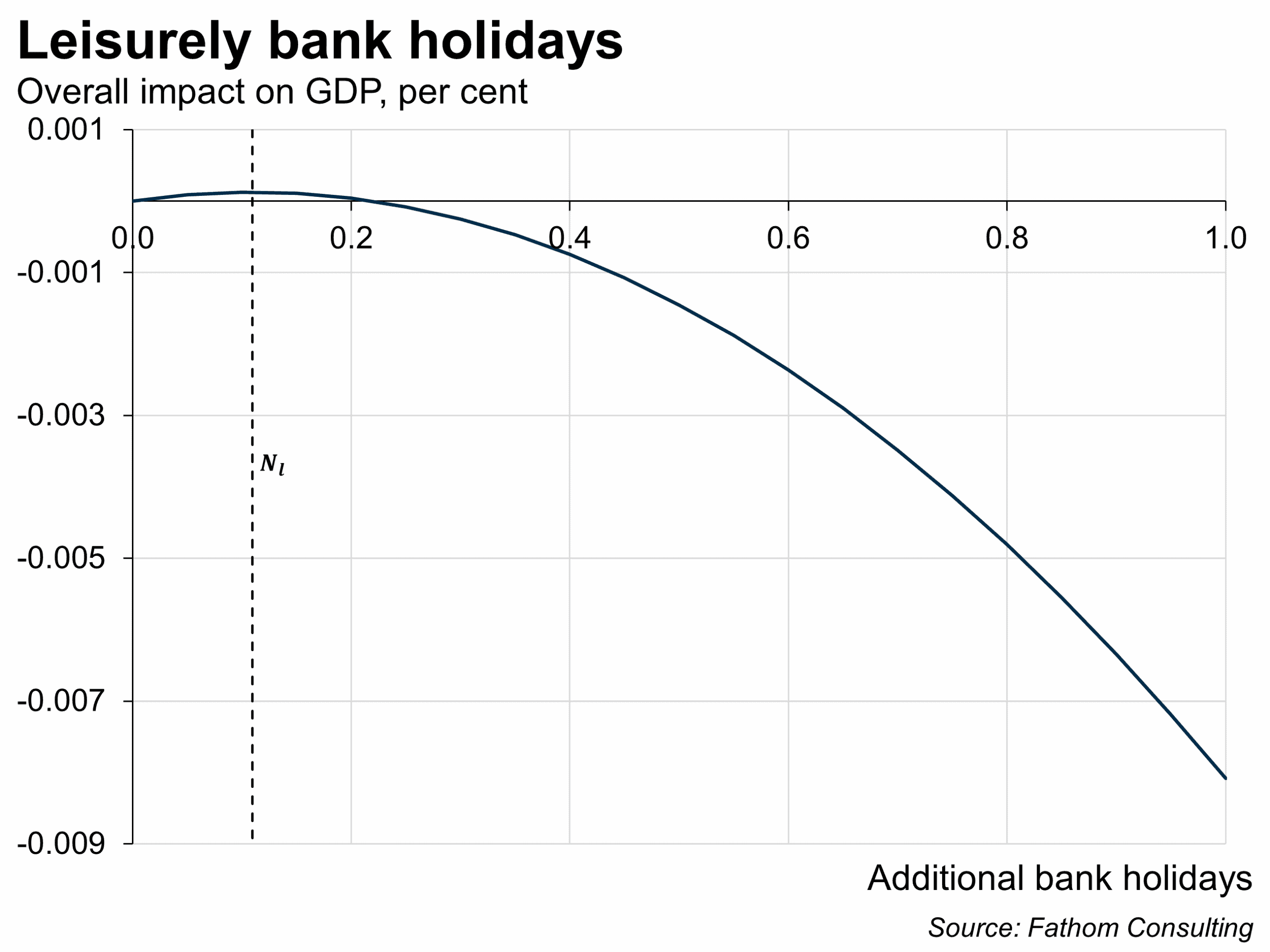

Here, the long-term implications of ‘leisure’ are clearly, as one would expect after several extended intoxicated weekends, decreases in productivity, which in turn causes GDP to contract. However, in the short term, Homo Britonomicus’ leisurely activities boost GDP, predominantly through gluttonous consumption![5] So there we have it, four different impacts on GDP in the short and long term.

So, out of a possible 44 extra bank holidays (assuming one extra a week minus the eight we already have), what does the model recommend when we combine the short- and long-term effects? Well with a few additional parameters, a touch of education system approved calculus and assumptions weaker than my 13th birthday party’s Piñata, I give you the optimum quantity of additional leisurely (Nl) and restful (Nr) bank holidays…

Nl= 0.1097, or 57 minutes off the 9-5.

Nr= 0…

Not the result many were hoping for… but the model does align with the UK government’s analysis, which estimated the cost of just one additional UK bank holiday, in terms of 2022 GDP, to be £2.4 billion. The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport report, published in February of 2022, was calculated by comparing GDP growth over the Golden (2002) and Diamond (2012) Jubilees (both of which featured an additional bank holiday), to the average growth of the same quarters in years without an extra bank holiday. Other estimates include £1.8 billion from the Centre for Economics and Business Research, and £831 million from PwC. With my parameters in place, one additional bank holiday would result in a contraction of 0.0081% for leisure and 0.3944% for rest, proportional to a cost of £208 million and £10.1 billion in terms of 2024 UK GDP at 2022 prices.

On the contrary, Barrera and Garrido (Barrera, 2018) find that, using a Schumpeterian model of economic growth, countries with a variety of domestic tourism destinations and populations with high levels of disposable income should implement more public holidays. However, they are unable to measure the tourism multiplier associated with additional national holidays. Indeed, using any model to measure the economic effects associated with an additional bank holiday is tricky, primarily because we have to construct a hypothetical estimate of what would have occurred if all other economic developments had taken place apart from the bank holiday. Of course, the British population doesn’t only consume alcohol or rest on a bank holiday. But assuming the composition of the UK economy is currently identical to how it was in 2012 and 2002 is almost as farfetched as supposing Homo Britonomicus’ two choices on May Day are rational.

So, can we expect additional bank holidays in the future? From the government’s current perspective, most likely not. But whether the UK should have more bank holidays in the years to come remains to be seen. Though output is paused in numerous sectors, bank holidays provide a tangible boost to much of the UK economy (not just hostelries). Furthermore, the improvement in well-being generated from a bank holiday, as well as its long-term impact on the economy, is often grossly undervalued. Hopefully the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport can give this improvement far greater consideration in their next report; maximising GDP shouldn’t be the only policy outcome. But who knows, perhaps a 4-day work week will compensate for the lack of 44 additional bank holidays anyway… Have a great long weekend all, especially you Andrew Bailey!

[1] Brits had been celebrating specific holidays for hundreds of years, long before the UK government made them official ‘bank holidays’ in 1871.

[2] Scotland has one extra public holiday on St Andrew’s day; Northern Ireland has two extra public holidays on St Patrick’s day and the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne.

[3] Excluding Martin Luther King day, Washington’s Birthday, Juneteenth National Independence day, Columbus day and Veterans day, all of which are less widely observed by private companies.

[4] For this model, ‘short term’ refers to a time-period of one day (a bank holiday), and ‘long term’ refers to a time-period of the whole year.

[5] It’s important to note that UK expenditure must outweigh the UK population’s daily wages, adjusted for the labour share of income, for consumption to raise GDP. What a person would have produced in a day is their wage plus the profits they create for their employer. This is equivalent to each person spending, on average, over £254 on their leisurely bank holiday.

Sources:

Barrera, F. & Garrido, N. (2018) Public holidays, tourism and economic growth. Tourism economics, 473-485.

Rosekind, M., Gregory, K. B., Mallis, M., Brandt, S., Seal, B. & Lerner, D. (2010) The Cost of Poor Sleep: Workplace Productivity Loss and Associated Costs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 91-98.

Dababneh, A. J. Swanson, N., & Shell, R. L. (2001). Impact of added rest breaks on the productivity and well being of workers. Ergonomics, 164-174.

Henning, R. A., Jacques, P. Kissel, G. V. & Sullivan, A. B. (1997) Frequent short rest breaks from computer work: effects on productivity and well-being at two field sites.

More by this author