A sideways look at economics

It has been brought to my attention that Bill and Ted will be returning to our screens in the not too distant future and there’s a buzz in the office among the older generation. I must confess, that the names only rang very dim and distant bells for me, but my friend Google has kindly filled in the gaps in my education. In the film Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey, Keanu Reeves’ character, Theodore “Ted” Logan, says to his friend Bill S. Preston Esq. (at a point in the plot when both are ghosts returned from the dead): “Dude, I totally possessed my dad”. What ensues is a scene in which Ted’s dad, a balding, respectable middle-aged man adopts the body language and mannerisms of the millennials of that age, Bill and Ted. I’m told by those old enough to remember the early nineties, that the film, the second of two, is as nice an expression of the zeitgeist of those times as you’ll find.

In the soon-to-be released third instalment, we’ll see their older selves: fathers (I gather, from the marketing blurb), with all the usual problems that entails. Bill and Ted’s big idea as young men: “Be excellent to each other”, promulgated by their brand of terrible rock music, hasn’t saved the world, as they had hoped it would. Surprise, surprise, the world is in its usual mess.

The gulf between generations persists in the real world. Today’s millennial generation is the first in some time to be doing worse than those that came before it. The latest suggestion about how we might redress the balance is a proposal from the Resolution Foundation that millennials should receive a 25th birthday present from the government of £10,000 to help pay for a deposit on a home, start a business or improve their education or skills.[1] As a millennial whose 25th birthday has sadly been and gone I felt a bit short-changed and was concerned I might have missed the boat. But apparently, all is not lost and there’s a plan to phase it in gradually for each cohort born after 1985. While the report doesn’t specify what proportion of the recipients are expected to choose each option, it’s likely that the majority would use the funds to put a deposit down on a house.It seems today’s young people would appreciate it if the older generation would “Be excellent to them”, through the gift of £10,000. Would that save the world?

If eligible recipients were to use the funds to enhance their education, improve their skillsets or start businesses, we’d certainly be in favour of such a proposal, given that the UK’s weak productivity picture is in urgent need of stimulation. However, we’re less convinced the impact on the UK housing market will be entirely positive.

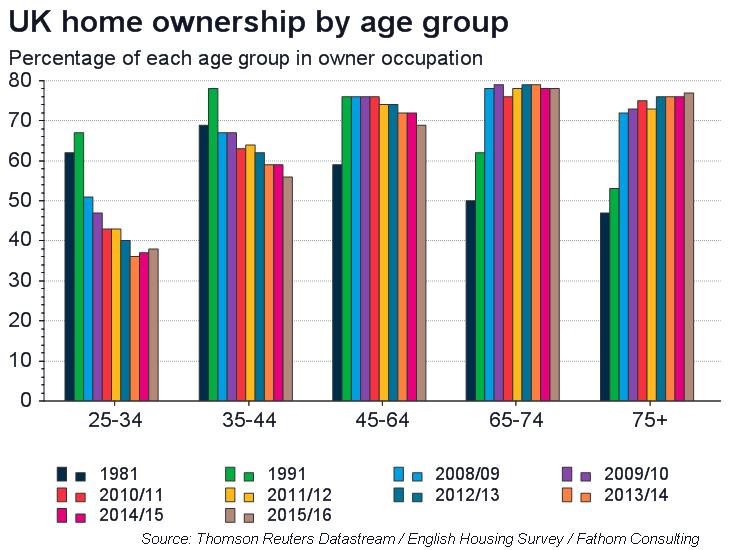

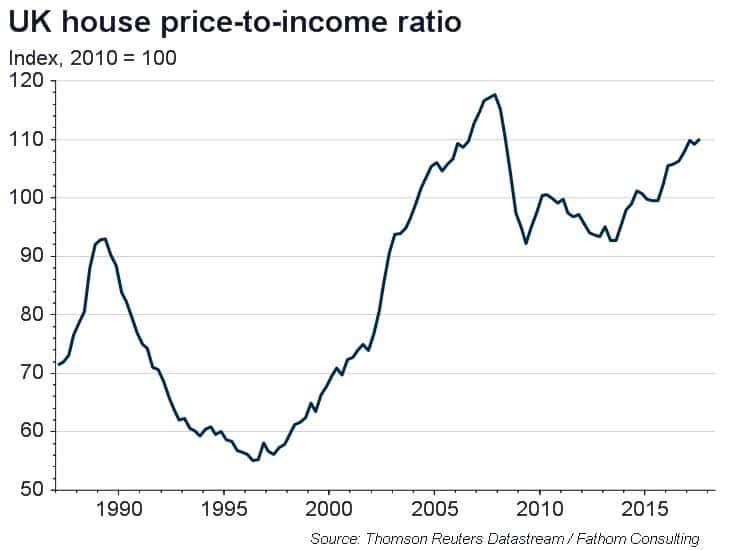

In terms of allowing young people a chance to get on the property ladder, this might seem like a great idea — despite a recent stabilisation, home ownership rates for young people are 28 percentage points lower than they were in the early nineties. Not surprising given that the UK’s house price-to-income ratio is almost 8 times annual earnings. Not only has it been inflated to within a whisker of its pre-recession peak, but it’s also well above its long-term average of around 2.5. Millennials have borne the brunt of the house price surge, with their ownership rates having declined to roughly half those for pensioners. Any attempt to reduce intergenerational inequality is sure to be welcomed and, let’s be honest, who doesn’t want free money! However, as is the case with a lot of things, if it sounds too good to be true then it probably is.

At Fathom, we’ve long argued that the majority of the post-crisis increase in UK house prices has been demand driven, brought about by exceptionally low real rates of interest and various ‘Help to Buy’ schemes — both of which act to further increase housing demand.

By granting millennials more funds for housing, the demand for houses will increase. Set against an unchanged supply of property, this would only serve to further inflate the house price bubble. Suppose the subsidy is spent entirely on housing. All that additional cash is basically transferred to people selling housing, i.e. people who tend to be rich and elderly and tend to save, at least partly counteracting the initial transfer of wealth from higher inheritance tax receipts. With the bulk of the additional cash likely to be saved, the effect on the real economy is likely to be negligible, with the policy only serving to inflate the already substantial house price bubble in the UK further and so doing just as much harm as good. The subsidy will not in the end benefit the Teds of the millennial generation but will instead, in a neat reversal, be totally possessed by their dad. Maybe not such an “excellent” idea after all.

[1] To fund this, they propose abolishing inheritance tax and replacing it with a lifetime recipients tax. Under the new system, the tax rate on gifts/inheritance would be lower, but so too would be the tax-free threshold (which would drop to £125,000). The Resolution Foundation estimates that these changes could be worth an additional £7bn per year to the government’s coffers.