A sideways look at economics

Readers like myself who have a healthy dose of cynicism about the holiday season will be relieved that today’s blog doesn’t revolve around Christmas (yet). Instead, I’ll be embracing my North American heritage and exploring Thanksgiving and the ensuing phenomenon of Black Friday.

Thanksgiving, which in the US falls on the fourth Thursday of November, is a secular holiday celebrated by families gathering for a long weekend and enjoying an indulgent meal of roast turkey together. It’s quite a wholesome affair; no gifts, no rampant consumerism, only fellowship and good food. But of course, that lack of materialistic spending needed addressing, so retailers came up with the idea of Black Friday — kicking off the Christmas shopping season with (ostensible) bargains and ungodly opening hours, and resulting in equally shocking and entertaining scenes of people queueing through the night and brawling over discounted HD TVs. The marketing ploy seems to have worked; some shoppers find the frenzy irresistible, and retail sales attributable to the November holiday have benefited.

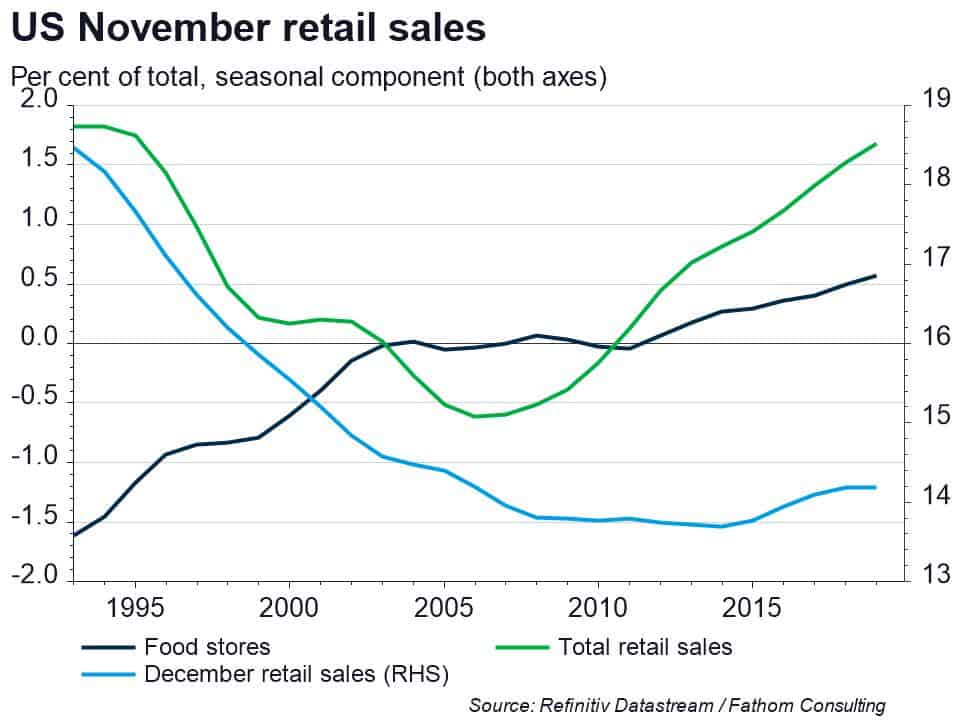

Seasonal patterns in economic data such as monthly retail sales are generally removed with seasonal-adjustment routines to allow meaningful comparison with the previous month. The difference between the unadjusted and adjusted series, then, represents the seasonal (as opposed to cyclical and irregular) component of the data. In most cases, we are quick to discard this seasonal component and only focus on adjusted data. However, in US retail sales, the seasonal component of November sales each year has fluctuated; after falling throughout the 1990s and 2000s, relative November sales have risen by over 2 percentage points of total spending. What’s more, retailers appear to have achieved this without it having an impact on the sales they make during the main Christmas shopping season in December. This suggests that consumers are spending more on the holiday season overall, rather than simply bringing forward their Christmas shopping into November.

Needless to say, stores in the UK and elsewhere have been keen to emulate the success of the Black Friday campaign (although the more intrinsic Thanksgiving celebrations don’t seem to have caught on as much).

Amazon UK began introducing Black Friday discounts in 2010. A few years later, bricks-and-mortar stores started introducing November offers too; coinciding with both rocketing seasonal sales and widely-reported fights, arrests and disturbances. Striking in the comparison between the US and UK is how, as a percentage of total monthly sales, the seasonal component in the UK is far greater than in the US, even before the arrival of Black Friday.

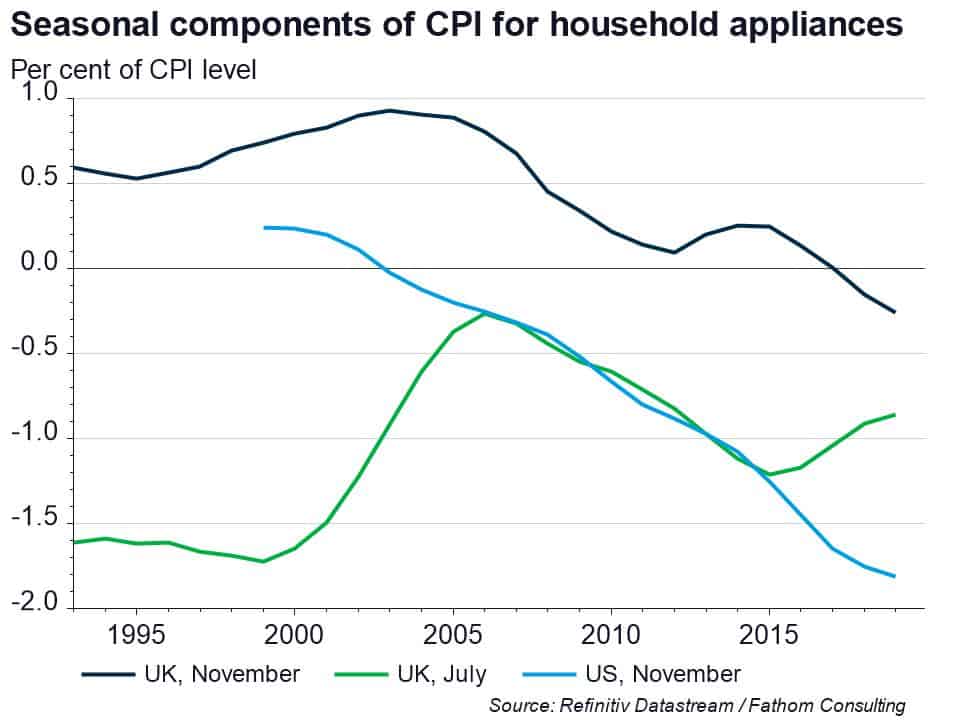

While November seasonal sales show little signs of slowing in the US, the trend in the UK seems to be tailing off. Perhaps people have decided that saving a few pounds isn’t worth the trouble of bargain-hunting, or they are heeding the advice of consumer watchdogs that many deals advertised on Black Friday aren’t as good as they seem. Indeed, while the seasonal component of CPI for household appliances — one of the most common categories of Black Friday discount — is lower in November than in any other month in the US, appliances in the UK can actually be bought more cheaply in July!

The data from the US also provide some consolation. Despite the consumerist frenzy that accompanies the end of this month, the seasonal component of food retail sales has either remained constant or climbed steadily. It seems that people have not forgotten the true spirit of Thanksgiving and appear just as willing as ever to spend money on a good meal in good company — or perhaps, they’re just fuelling up more to face the crowds the day after. Either way, I definitely think a delicious roast with friends and family sounds like a great way to spend an evening, and to forget at least temporarily about the annoyingly repetitive Christmas jingles I’ll no doubt have to endure in the Christmas shopping season which has now, officially, begun.