A sideways look at economics

Buy now, pay later (BNPL) credit has exploded in popularity since the pandemic. With its tempting zero-percent interest rates offered to anyone who can pass a ‘soft’ credit check, it is not hard to see the appeal. Sure, it can make sense to spread medium-size, infrequent purchases into several payments to ease the liquidity constraints of a monthly paycheck. But with BNPL payment now available on food delivery services such as Uber Eats, has it gone too far?

For those unfamiliar, BNPL is a predominantly interest-free form of credit that lets shoppers defer payment at checkout. Users commonly pay 25% up front before settling the balance in three equal instalments over the next six to eight weeks. Because approval usually involves only a ‘soft’ credit check that leaves no visible footprint on a credit report, the product has resonated with younger consumers, with 56% of UK Gen Z and 63% of Millennials having used BNPL, versus 42% of adults overall. By March 2023 it already accounted for 14% of all UK online transactions. That growth looks set to continue, but whether this is good for consumers is up for debate. Free credit certainly beats high-interest alternatives, yet 57% of users later regretted a BNPL purchase after realising the item was too expensive, and usage has been linked to an 8.9% rise in overdraft fees — evidence that the ‘zero-cost’ promise can come with hidden downsides.

Whether BNPL is beneficial or not will of course vary depending on consumer behaviour: whether they act rationally — weighing up the true costs and benefits of each purchase — or whether they are impulsive, myopic or susceptible to psychological tricks. But before we can consider each scenario, we first need to understand the economics of the BNPL model. Why would merchants, through paying higher-than-usual transaction fees,[1] effectively subsidise the consumer’s interest cost?

Merchants swallow BNPL’s higher transaction fees because it lets them price-discriminate cleanly. By splitting shoppers into cash consumers (who can pay upfront and have a higher willingness to pay) and credit consumers (who are more price-sensitive), retailers can keep list prices high for the first group while quietly discounting for the second. With traditional credit, interest payments reverse that logic as credit consumers end up paying more in real terms. BNPL removes those finance charges and provides an interest-free period, so credit shoppers effectively pay the sticker price minus the value of the free loan, while cash shoppers pay the full sticker. That hidden discount boosts sales to budget-constrained buyers without visibly cutting shelf prices, and the resulting volume and margin gains are intended to more than offset the extra BNPL fee.

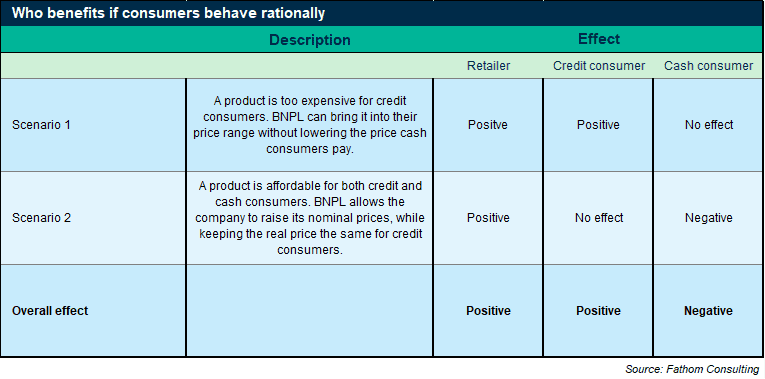

Now, with the BNPL framework laid out, let’s look at the case where consumers act rationally. Consider two simplified scenarios where retailers utilise price discrimination:

As retailers benefit from both scenarios, it is fair to say they are the clear winners in a BNPL world, even if consumers behave optimally. While rational credit consumers also benefit overall, perhaps the most interesting and somewhat surprising conclusion is that BNPL is a net detriment to cash consumers, despite their choosing not to use it.

However, so far, we have assumed that cash consumers remain cash consumers even after BNPL is introduced, although it could be argued that for perfectly rational consumers, they should take advantage of the (albeit small) absolute BNPL discount.[2]

But, before you rush to set up a BNPL account, let’s consider a more probable case where consumers are at least somewhat irrational, and don’t consider the true costs and benefits when using BNPL. Perhaps they overvalue the benefits of current consumption or they underestimate their default risk. While both irrationalities may cause overconsumption, they are common to all types of loans and don’t quite explain the unique risks of BNPL.

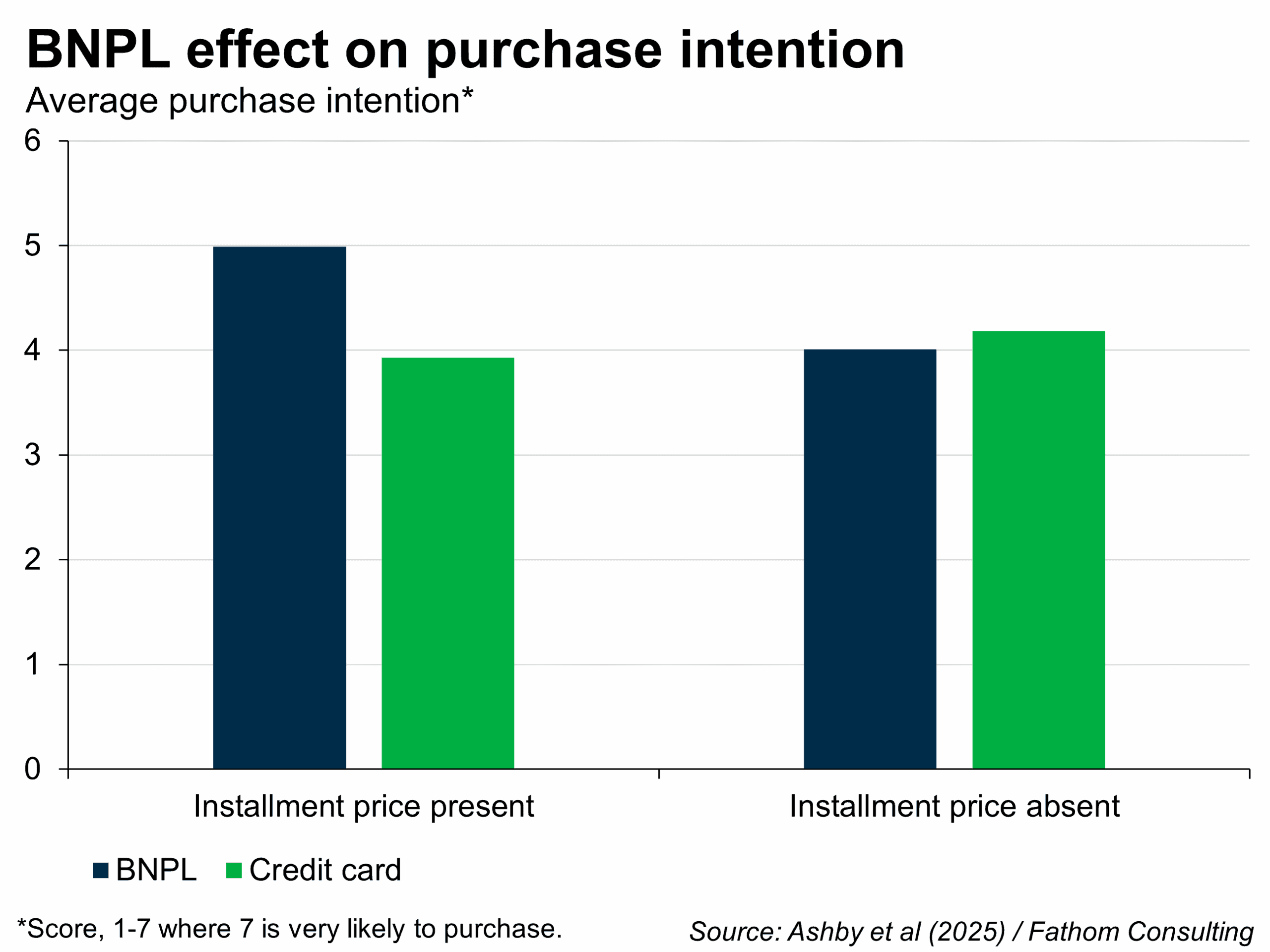

For that, we can look to the numerosity heuristic — humans are instinctively drawn to larger absolute numbers, a behaviour that can distort our perception and make it harder to compare identical values. Consider 10,000 metres vs 10 kilometres or 84 days vs 12 weeks. People (and other animals for that matter!) subconsciously view more numerous values as larger, regardless of the units. In the BNPL case, four £19.99 payments may seem less expensive than £79.96. Indeed, a study found that BNPL significantly reduced perceived expensiveness and increased purchase intention — but only when the instalment prices were shown. This means if consumers have to do their own maths, e.g.,‘£128, also payable in four instalments’, then BNPL has no effect. But if the instalment price was laid out for them, i.e., ‘£128, or four payments of £32’, then BNPL has a significant effect. If this isn’t evidence of consumer irrationality, then it’s hard to know what is…

The chart above demonstrates the psychological pull of BNPL, and users who underestimate the full cost of a purchase may subsequently overconsume, which could completely outweigh the cost-saving benefits of the interest-free loan.

The credit provider Klarna claims that BNPL can increase the average order value by 20–30% and raise conversion rates[3] by up to 44% — which helps explain why merchants are willing to pay higher transaction fees to offer a BNPL payment. These figures seem substantially too high to be solely explained by the interest-free discount, suggesting that there is at least a degree of irrationality at play. BNPL evidently encourages consumers to spend more, but does it encourage them to spend beyond their means? Well, BNPL delinquencies are not dissimilar to other forms of credit — a fact that, on the surface, suggests not. However, if we were to dig a little deeper, characteristic BNPL features like auto-pay, as well as credit restrictions that are implemented after late payments, may encourage consumers to prioritise their BNPL repayments by diverting money away from other debts.

So who wins in a BNPL world? Well, for the ultra-rational among you, perhaps you do. For others, perhaps you too were influenced by the numerosity heuristic. And for those who have steered clear all together (or were blissfully unaware for that matter), maybe you have unknowingly been the victim of price discrimination thanks to BNPL. Klarna, for now, also appear to be winning. By nudging consumers to spend more, they are able to justify higher merchant fees. However, they also assume the credit risk and could face rising defaults in the event of a recession. Moreover, the ability to encourage increased spending may not last for ever. Governments have clocked the potential risks of BNPL, with the UK government announcing that regulation is set to take effect in 2026, which aims to increase affordability checks and provide more transparent details to customers about the nature of BNPL loans. But maybe, just maybe, a simple ban on displaying instalment prices would do the trick…

[1] BNPL fees typically range from 2-8%, compared to credit card fees, which are usually around 2.9% on e-commerce transactions. How BNPL Companies Make Money? | Scope of Buy Now Pay Later

[2] The BNPL discount is not that significant for a cash consumer switching to BNPL. For example, if we assume a 4% AER savings account rate, the money saved on a £100 purchase split into four payments over six weeks is about £0.22. But for a credit consumer paying a conservative estimate of 20% APR on a credit card/overdraft, this discount is a more significant £1.37.

[3] Conversion rates are the percentage of users who complete a transaction after adding a product to their basket.

More by this Author