A sideways look at economics

Across Europe, voters are currently casting their ballots in the European parliamentary elections. However, Europeans already voted in a similarly contentious (albeit less consequential) poll last Saturday to crown this year’s winner of the Eurovision Song Contest (ESC). I must admit, I’m not a particularly avid follower of the annual spectacle (except for the occasional incongruously alternative acts such as latex-laden industrial or theatrical shock rock), but the general enthusiasm for the ESC certainly rivals that of political elections, with the 2018 ESC’s 189 million viewers easily contending in numbers with the last European election’s 167 million voters.

In the annual television contest, over 40 European (and slightly less European, such as Israel or Australia) countries enter an artist to perform an original song, with countries then voting to select the most popular song each year. While the results should reflect both the artistic merit of the songs themselves and the creativity of the stage performances, votes have often been accused of being politically motivated, with certain countries voting for each other based on general attitudes towards other countries, rather than on the merits of the performances. There is no substantial reward for winning the ESC, but countries might still vote tactically to secure bragging rights for a good result – or in some cases, like the UK this year, be spared the embarrassment of coming last. So, is there any evidence of song contest collusion in the ESC?

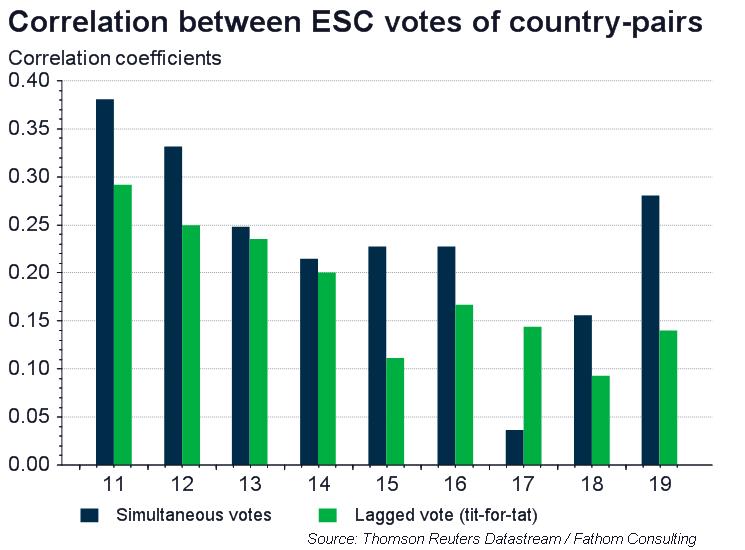

After all but 26 competitors have been weeded out in semi-finals, the remaining countries perform in a final show. Each country (including those who didn’t make it to the final) then allocates votes across all the other countries based on a combination of jury votes from the national broadcasting corporation and public votes submitted by phone. There does seem to be an element of implicit collusion among countries: the correlation between the votes countries give each other (i.e. between the vote share of country A to country B, and that of B to A) is positive and relatively persistent over a sample of the past ten years. This is perhaps a bit surprising, since this sort of collusion ought to throw up a prisoner’s dilemma-esque trust problem; since voting happens simultaneously, voters are unable to see which countries are voting for their own country and would thus be unable to respond in kind. Of course, there are plenty of reasons apart from collusion why votes could be correlated like this. Due to the immense variety of acts (ranging from the aforementioned BDSM-themed electronic over chart-toppers like ABBA to a capella folk music), votes are often a reflection of different tastes, and a country is more likely to both vote for, and field, a candidate that aligns with its residents’ tastes.

However, the ESC has been aired each year since its inception in 1956 and could thus be seen as a multi-stage game. A possible solution to sustaining collusion in an infinite game is a tit-for-tat strategy, where each player mimics the opponents’ previous turn. In the context of the ESC, there is indeed evidence that country A’s votes share for country B is dependent on B’s vote for A in the previous year – although the correlation is less strong than that of simultaneous votes between countries.

What’s striking across both of the correlation coefficients over time is how there has been noticeable downward trend, with virtually no similarity in cross-country votes in 2017. If this is indeed evidence of an implicit form of collusion, it would require a certain level of trust and mutual understanding between countries to be sustained. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the decline in cooperative patterns in Eurovision voting coincided with a wave of Euroscepticism and a general distrust of multilateralism across Europe and the world.

It would be worrying if shifting attitudes to European cooperation and international collaboration have pervaded relatively trivial pop culture events, too. However, it’s not all doom and gloom – in this year’s contest, the votes once again showed evidence of similar voting across countries, and the region may be returning to a more united euro vision. The bad news is that not only did the UK come last this year, but its score was revised further downwards this week due to a calculation error. Perhaps the collusion taking this place this year was a coordinated backlash against the ongoing chaos of Brexit (just as the European elections may turn out to be, too).