A sideways look at economics

During a particularly hard interval session[1] with my athletics club, by the time we got to the later repetitions I felt as if I were struggling up London’s version of Mount Everest. (In reality it was just a slight incline.) Due to my incessant moaning about how much I HATED hills, the club coach gave me some advice. As I was testing it out and trying to distract myself from the burning in my quads, it got me thinking about how the mechanics of hill running could be applied to the growth path of many economies worldwide. Farfetched, I know, but at Fathom we can relate just about anything to a good lesson for the macroeconomic environment…

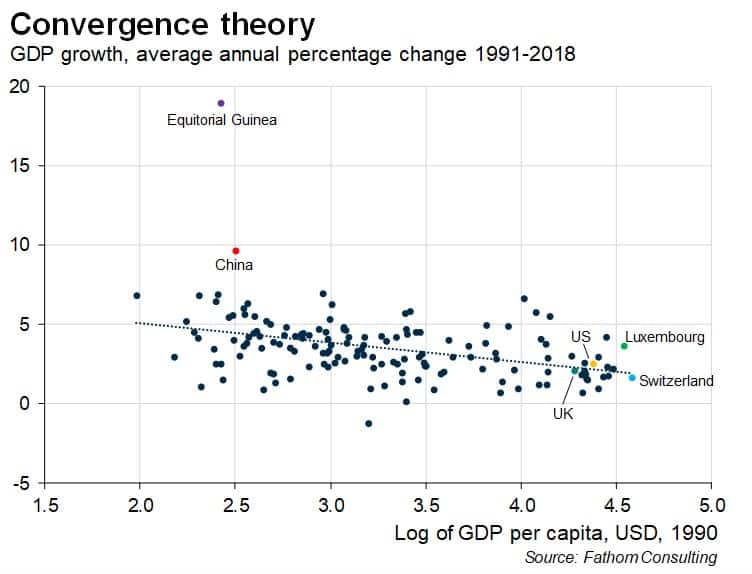

The theory of convergence, or the catch-up effect, is a basic growth theory that postulates that less-developed economies will experience faster levels of growth as they ‘catch up’ with their developed counterparts. Like any economic theory, there are many limitations to the idea. For example, it’s conditional on factors such as the quality of institutions, but in its simplest form we have seen evidence that poorer economies can grow much faster than wealthier economies in order to converge to their levels of income.[2] There’s no more striking example of this than modern-day China.

A poorer economy is starting from a lower base, they can exploit economies of scale, replicate technologies and institutions of developed economies, and participate in global markets to drive their growth rate higher. By contrast, wealthier economies, further along the development scale, find themselves struggling with diminishing returns to investment, and can no longer rely on old drivers of growth.

I liken this phenomenon to running up hills in an interval session. We work in repetitions. The first journey up the hill, the first rep, is a battle, but it’s not a full-out war. There’s still energy in the legs, the blood is still pumping, and regardless of your form, you can get to the summit. This represents the developing economies in this scenario; they’re at the initial stage of their industrialisation. There is spare capacity in the economy and power in the legs to increase the growth path of the economy.

However, once a nation starts moving further down the development scale, it suddenly becomes a lot harder to maintain that pace. Now, we are on around rep four. The lactic acid is building, the legs start feeling heavy, and that energy needed to start the next rep is dwindling. Suddenly, it’s harder to boost productivity; economies of scale are turning into diseconomies of scale, and the effort needed to increase GDP growth further is much more challenging, as is running up that hill.

Then you get to the last rep; we’re in a Japan world now. The lactic acid has built up so much that the muscles are burning and fatigued. The finish line is in sight, but so is that incline. It takes every bone in the body to push up the hill, and the pace has taken a nosedive. Welcome to Japan and stagnation. Japan is the third largest economy by nominal GDP, yet for the last 20 years it has been struggling, plagued with deflation, high debt, low productivity and ultra-low interest rates, constricting efforts to boost the economy further. In running terms, it’s in a sorry state looking up at the mountain ahead, with little energy to push on.

However, this isn’t necessarily the fate for every runner, or every economy. The ultimate aim of interval training is to keep a consistent pace across every rep. People that manage that, seem to survive up that last hill. I wasn’t one of those people. It turned out that I was draining energy early on by trying to maintain a longer stride length, despite the difficulties posed by the incline, thinking it would get me to the top faster. In reality, my coach explained that I needed to change tactics and by shorten my stride to conserve my energy for the later reps. The key was measured, sustainable steps.

Like hill running, sustainable steps could prove beneficial to the economies that are around rep four in the development scale and are beginning to tire. China is a great example of this. Economic data out of the country show that progress is weakening, and that is just what the slightly dubious official measures report. Forecasters, Fathom included, are concerned about the potential for future ‘Japanification’ of China.

Despite this concern, China is only halfway through its interval session. With correct measures, they can run, and grow, more sustainably. For me, it was all about my stride. For China, it’s about the drivers of growth. In order to make it up the next hill in a sustainable manner, policymakers ought to encourage a move away from away from the credit- and investment-led growth model towards a more balanced economy in which private consumption plays a greater role. A consequence of this type of rebalancing is the possibility of slower growth. However, this growth is far more likely to be sustained. As the saying goes, slow and steady wins the race.

After all this deliberation, when the session ended, I came to the conclusion that solving world problems is stressful and, unlike China, when it comes to running, the famous words of Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell “Ain’t no mountain high enough” most definitely don’t apply. Give me a low valley any day…

[1] For the majority of the sane population that don’t find running in any way enjoyable, interval sessions involve running hard for short periods, followed by recovery periods. You then repeat this process a number of times.

[2] In Convergence and Modernization Revisited Robert Barro has suggested that the conditional convergence rate is between 1.7% and 2.4% per year.