A sideways look at economics

“Democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time…”

Winston Churchill, 1947

Fathom has its annual office awayday today – lots of brainstorms, idea showers, blue-sky thinking and so on, and that’s just over cocktails in the evening. But there is one over-arching issue: what about the food?

Our options were constrained: we all had to eat the same meal, except if we wanted vegetarian food. Then, excluding the vegetarian options there were choices between meat and fish. And, within the category of ‘meat’, there was a choice of lamb or beef.

Essentially, three options for the whole team: beef, lamb or fish; with an opt-out for vegetarians. A simple problem, no?

No.

The question was how to set up the vote. First we had a show of hands for the fish option, and another for meat. It returned a majority for meat. Then we had a show of hands within the meat option for beef or lamb, with a majority for beef. But some complaints were registered at that point: what if I prefer fish to beef, but not to lamb? And what if, instead of beef, I choose to opt out and go for the veggie option – should my initial vote for meat still be counted? At that moment, it was revealed that there was also an option for duck. Chaos ensued.

The Fathom team is largely composed of economists, well-known for our ability to hold several opinions at once – opinions that, to civilians, might seem self-contradictory; and equally notorious for our love of argument. The chances of resolving these issues satisfactorily and also getting our work done that day were vanishingly small. Impossible, even.

The late, great Ken Arrow described these problems elegantly in his famous “impossibility theorem”, that states that there is no fair (rank-order) voting system, except in very particular circumstances. There is no way, in other words, of translating the preferences of an electorate across three or more options fairly.

One of the exceptions to that rule that Arrow acknowledged is the case where there is only one voter – a ‘dictator’, as Arrow put it. Fortunately, for all our sanity, a dictator emerged to solve Fathom’s problem.

Beef.

Anyone got beef with that: talk to the CEO. Hopefully, other discussions today will be less dictatorial than that, but we’ll see.

The problem at Fathom, and its resolution, are illustrative of a wider tendency. Fathom illustrates in micro something that is arguably in train right now in a macro sense too.

Arrow thought that most voting systems would deliver results that were generally perceived as fair most of the time. But some of the time that would not be the case, whatever voting system was used. If that perception of unfairness becomes pervasive, there is always a risk that the authoritarian ‘solution’ will emerge across society as a whole.

For example: the Scottish independence referendum offered a binary choice, and returned a decision to stay in the UK. But, since then, the UK as a whole has voted to leave the European Union. Had voters in Scotland who voted to stay in the UK been asked ‘would you prefer to stay in the UK once the UK has left the EU?’, they might have voted differently. Similarly, those who voted to leave the UK might have voted differently too…

In the US Presidential election, President Trump won the electoral college but lost the popular vote. Although it is not the first time that has happened, it has led to a growing sense of unfairness – both among those who voted for Clinton and now feel that ‘really’ they should have won, and on the part of President Trump himself who disputes the veracity of the popular vote as officially recorded.

In the forthcoming French Presidential elections, all but the two candidates with the highest share of the vote in the first round are eliminated from the second round. Those voters who would really have preferred one of the eliminated candidates are then forced to make a binary choice in the second round – and the outcome will therefore be influenced by who gets through to the second round. For example, some voters might choose anyone ahead of Fillon, and anyone but Fillon ahead of Le Pen. So a second round that is Fillon vs Le Pen will deliver their votes to Le Pen, whom any other candidate might have defeated.

As Arrow demonstrated, there is no ‘fair’ way of resolving these issues. The important thing in democracies is that most people judge the outcome to be fair enough most of the time. If that general acceptance erodes away, then watch out for the emergence of would-be dictators the world over…

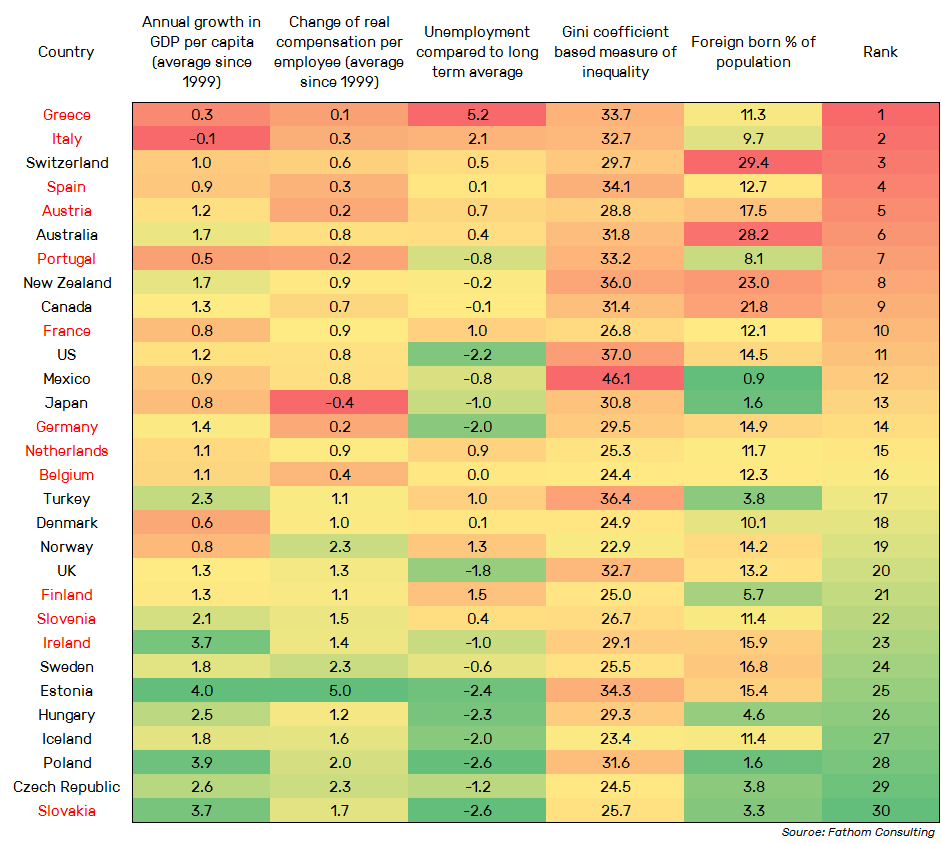

We have attempted to quantify the vulnerability to authoritarianism across countries, looking at a variety of different metrics that might capture or lead to a sense of dissatisfaction in the electorate – a sense of unfairness around the current political settlement. The results, in rank order, are shown in the table below.

Vulnerability to authoritarianism