A sideways look at economics

Bruce Willis, Jeff Bezos, Stanley Tucci, Homer Simpson, Matt Lucas…the list of famous men with infamous hairlines is (ironically) long and growing. The psychological literature has plenty to say on the benefits accruing to them because of their baldness. A Wharton study found that men with shaved heads are perceived as more dominant, taller and stronger than their natural selves.[1] But the economics profession also has something to say on the matter via the late William Baumol — who also had a shaved head in his later years — in the form of his theory of cost disease.

Baumol’s cost disease was originally applied to understanding why salaries are constantly rising in the performing arts despite the sector experiencing almost no increase in productivity. The same number of musicians is required for a string quartet to play one of Beethoven’s chamber pieces today as was needed 100 years ago. Despite the lack of an increase in productivity, string quartets are paid far more than they were 100 years ago in nominal terms. Baumol reasoned that if wages for string quartets did not increase over time, musicians would leave the performing arts and move to sectors with higher wages. To prevent this, wages, and therefore prices, must rise. However, sectors with rising productivity can increase wages without increasing prices.

In his seminal paper, Baumol[2] differentiated industries into technologically ‘progressive’ activities — those that could utilise technological innovations, automation and capital accumulation to increase productivity — and ‘non-progressive’ activities that only permit sporadic increases in productivity. He argued that ‘progressive’ industries treat labour as an instrument to help achieve a final product, as in goods manufacturing, while ‘non-progressive’ industries treat the labour as the final product, as in the string quartet.

Individuals who spend a larger share of their budget on goods and services that are made in ‘non-progressive’ industries will experience a higher rate of inflation. One example of this is haircuts and electric clippers.

The haircut your hairdresser gives you today is not dramatically more productive than the haircut given to your grandparents or even their grandparents. Whilst some quality innovations have been made — Leo Wahl patenting the electric clipper in 1919, the Roffler-Kut system and even ear candling — they have had little impact on the labour input required to produce a single haircut. And in many cases the increase in the quality of haircuts is highly questionable (just think back to Paul Pogba’s leopard print look at Juventus). This has resulted in slow productivity growth for the sector and a severe case of Baumol’s cost disease.

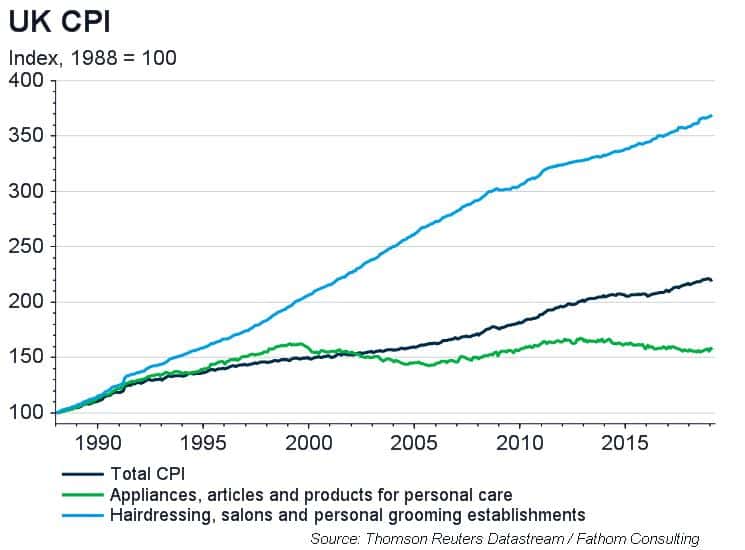

However, the production cost of manufactured goods, like the electric clipper, have continued to fall over time with increasing productivity and competition in the manufacturing sector resulting in slower price rises — or sometimes even price decreases. Since 1988, the price of hairdressing, salons and grooming establishments has risen by more than four times as much as the price of appliances, articles and products for personal care (including electric clippers).

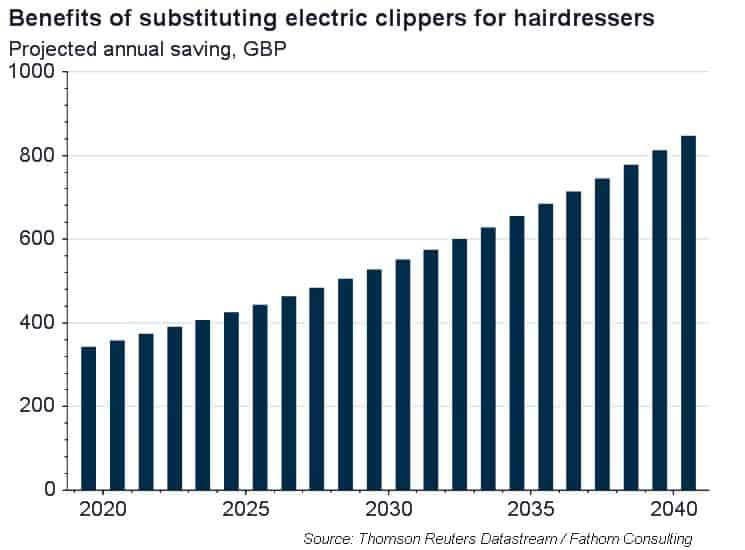

There is therefore a dual benefit from substituting the electric clippers for the hairdresser. First, the price is already lower. My electric clippers cost £35 while Brian Davidson reported in a previous blog that a haircut in Shoreditch will set you back £30. If the shaver lasts for, a pessimistic, two years and assuming one haircut a month, you could make an annual saving of £342.50. Second, the saving relative to the counterfactual world in which you still go to the hairdressers will only increase over time as the price of haircuts rises at a faster rate than the price of electric clippers due to Baumol’s cost disease.

If the rates of inflation for haircuts and electric clippers are in line with their historical averages, 4.3 per cent and 1.5 per cent respectively, you would save almost £850 in 2040. Despite the benefits presented in this blog, the Wharton study also found that the perceived attractiveness of men with shaved heads is lower. So, if the saving on haircuts isn’t enough to tempt you…think of all the money you could save on dating.

[1] Albert E. Mannes, ‘Shorn scalps and perceptions of male dominance’, Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4/2 (2013), pp. 198-205.

[2] William J. Baumol, ‘Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: the anatomy of urban crisis’, The American Economic Review, 57/3 (1967), pp. 415-426.