A sideways look at economics

The day before my holiday to Greece this summer, I rolled out of bed at 11am to horrific news. My dad had just got a haircut. A haircut!? The day before we fly to Greece!? Outrageous. I disgruntledly explained the Balassa-Samuelson effect, i.e. lower productivity means that services in less developed countries tend to be cheaper than in more developed countries. (I’d like to point out that my dad actually almost always gets a haircut when we go on holiday, but turns out this is because he sees geographical variation in haircuts as a collector’s item, not as a sound economic decision.) This got me thinking. Why don’t people do what economic models say they should?

This is the stick that non-economists often use to beat economists with. Homo Economicus is dead, theoretical models caused the crisis, etc. To their credit, academic economists have taken much of this criticism on board, reflected in the rise of behavioural economics. As always, however, there are two ways to tackle this problem. I’m not an academic, and therefore probably can’t contribute to advancing the discipline. I can, however, become Homo Economicus and make economists’ lives much easier. Maybe not in the traditional ‘perfectly rational’ sense, but in the sense that I stay informed of important economic research and abide by its teachings.

With this in mind, I have made the following decisions:

I will never buy a second-hand car

In any second-hand market, especially one with poor regulation, information asymmetry gives sellers the upper hand. It also results in only poor-quality goods being sold. In ‘The Market for “Lemons”’, George Akerlof explains how the uncertainty about the quality of the car means that buyers would only be willing to pay an amount in between their valuation of a low-quality and high-quality car. Sellers are unwilling to sell their high-quality cars at this lower price, driving out such cars from the market. Stay away from private sellers.

I will never cooperate

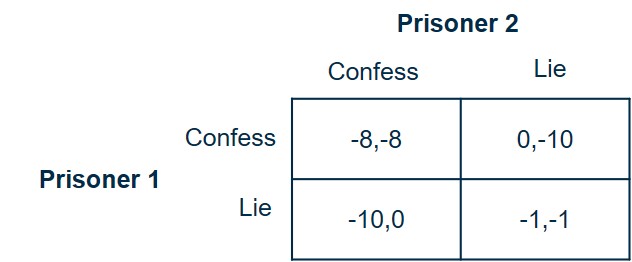

The key take from ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’, the best-known game in game theory, is that you should always think of yourself, even if it leads to a worse overall outcome.

Consider the matrix above. The Nash Equilibrium, or the only combination of strategies for Prisoner 1 and Prisoner 2 from which neither wishes to deviate, is for both to confess. Of course, this is an inefficient outcome, and if both prisoners were to lie the total pay-off would increase from -8 to -2. There may be coooperation in repeated games, but then again, I don’t plan on finding myself in prison more than once.[1]

I will never use a map

Meese and Rogoff, in 1983, showed that widely used exchange rate models were no better in forecasting future exchange rates than a random walk model. A random walk is a path that follows no pattern. Flip a coin. If it’s heads you turn left, and if it’s tails you turn right. This should have an equal chance of getting me to my desired destination.

I will never bring lunch to work

To some, bringing lunch to work is a way to tighten the purse strings. After all, anything remotely satisfying will set you back over £5 a day, or £25 a week, or £100 a month. Bring your own meal, and it’s free! Wrong. There’s no such thing as a free lunch. I earn over £12 an hour and value my free time considerably more, therefore 15 minutes spent making a lentil salad for tomorrow sets me back well over £3. A Tesco’s meal deal is £3 and gets me Clubcard points, and is therefore the better choice.

I will treat myself

When I’m feeling blue, I will shop. John Maynard Keynes hypothesised that spending was the only way out of the Great Depression in the 1930s. Despite a fall in demand for labour, people are unwilling to accept pay cuts and therefore the market for labour will not clear. This requires government spending to increase aggregate demand and return the economy to equilibrium. In fact, he supported deficit spending. So, I can max out my credit card.

Clearly this is very peculiar behaviour and is just a partial interpretation of the literature. But herein lies the problem. Economics is a broad church, and a complex one at that. There’s really no perfect way to incorporate human behaviour into economic theory. The point of models is to strip back the complexity to reveal the underlying mechanism, not to explain every aspect of human behaviour. Rationality is boring anyway.

[1] I’m not the first economist at Fathom to apply the Nash Equilibrium to problems in my daily life: https://www.fathom-consulting.com/what-economics-has-taught-me-about-myself/.