A sideways look at economics

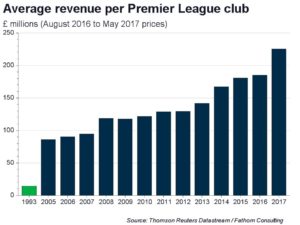

What is the primary challenge facing UK PLC at present? If you thought Brexit, think again. The correct answer, as regular readers will be aware, is the economy’s dismal productivity performance. Data released earlier this week showed that output per hour fell in the second quarter, and is now back below its pre-crisis peak. That is an unprecedented postwar decade of near-zero productivity growth. But there is one shining beacon of hope. The Premier League (PL), celebrating its 25th birthday this month, has seen its revenues soar. Even stripping out the effects of inflation, the income received by all clubs has jumped from £0.3 billion in 1992/3 to £4.5 billion (with both figures at constant 2016/17 prices). And this impressive performance has taken place against the backdrop of a contracting workforce – at the start of the 1995/96 season, the number of teams was reduced from 22 to 20.

In spite of its success, English football’s top tier is not short of critics. One of the most common complaints relates to an increasing overseas presence. At the inaugural weekend, 13 foreign nationals took to the pitch. Last weekend that number had risen to 220. Some think that this has blocked the promotion of young, home-grown talent. In truth, of course, gifted British players do not struggle to make it in the PL because of some exogenous increase in the number imported from overseas. PL clubs are signing more foreign players because there is a lack of suitable domestic alternatives. Part of the reason may be subpar coaching. The latest data show just 1,395 people in England hold one of UEFA’s top-two coaching badges. That compares to figures of 6,937 in Germany, and 15,423 in Spain. Regarding the UK workforce more broadly, there is a similar shortfall when it comes to schooling. The OECD’s PISA tests, which measure educational attainment across countries, show that the UK ranks 27th in mathematical achievement, and it is slipping back.

When it comes to foreign ownership, research from the Bank of England suggests this is probably good for the PL’s bottom line too. The Bank’s analysis suggests three reasons why foreign-owned firms boost UK productivity: they invest more in R&D; they are better managed; and they promote the diffusion of ideas. Oligarch owners seem to tick all boxes. Their willingness to invest in on-field talent cannot be questioned (Arsenal excluded). On management too, foreigners have a better record (Arsenal included). Aside from Sir Alex Ferguson, no British manager has ever won the PL. That may be why their share within the PL total has dropped from 95% to 20%.

When it comes to judging the impact of foreign talent on the PL, and indeed on the UK economy more broadly, Brexit may provide an answer. It is almost guaranteed that the vote to leave will make it more difficult for EU nationals to play in the PL. But even before the official divorce, it is having an effect. Reports in Dutch newspaper, De Telegraaf, earlier this week, suggested that negotiations between Ajax and Tottenham had broken down regarding the transfer of Davinson Sanchez. The disagreement reflected Ajax’s demand for a 6% increase on the initially agreed sterling fee to reflect an equivalent rise in EURGBP over the intervening period. With sterling holding its own against the common currency over the past couple of days, the dispute has now been resolved, and Mr Sanchez is set to be the newest addition to North London.

There is no magic bullet that can in one fell swoop improve the performance of British-born players on the pitch, just as there is no quick and easy solution to the UK’s productivity crisis. But investment in coaching, and in education, could each have a positive impact over the medium term. In the meantime, there are plenty of Spanish footballers and German engineering graduates who can help plug the gap. They may, however, ask for their salaries to be paid in euros.