A sideways look at economics

My dad occasionally likes to gift me books that serve a double purpose. So when he spotted one that covered both my work and my passion for cooking, he thought, ‘Bingo!’ And so to Edible Economics: The World in 17 Dishes, where author Ha-Joon Chang, a professor at SOAS University of London, aims to make economic concepts more digestible by serving them up alongside stories about… food!

To give you a flavour of what’s covered in the book, in the chapter on okra, Chang delves into the history of the slave trade, challenging the notions of freedom often championed by free-market enthusiasts. Looking to his noodle-loving home nation of South Korea, he discusses the significance of protecting infant industries, a key ingredient in South Korea’s economic success. And in a chapter on chilli, he lifts the lid on unpaid care work which is too often undervalued and neglected, despite the fact these activities would make up roughly 30-40% of GDP if valued at market prices. However, it’s Chang’s chapter on lime and the subsequent discussion on climate change which captured my attention most, sparking the inspiration for today’s blog. So, are you ready to tuck in?

Chang begins the chapter by recounting how the British Navy provided sailors with rations of limes or lemon juice to prevent scurvy, a condition resulting from vitamin C deficiency which between the 16th and 18th centuries wiped out sailors on transatlantic voyages who spent prolonged periods at sea without access to fresh food. This practice was what earned Brits the nickname ‘Limeys’ among American sailors. Chang then takes his readers on a delightful diversion via the association between limes and sugar cane in Brazil’s national cocktail, the caipirinha, and the role of Brazilian sugar cane in making bio-ethanol, concluding with a discussion on the importance of bio-fuels in achieving the energy transition to net zero emissions.

All of this set me to thinking. This change to sailors’ eating habits was transformative and within just over a decade of the policy, scurvy virtually disappeared in the Royal Navy. I wondered whether in today’s modern society, changing our own eating habits could lead to another type of transformative change — by reducing our individual carbon footprints through what we eat.

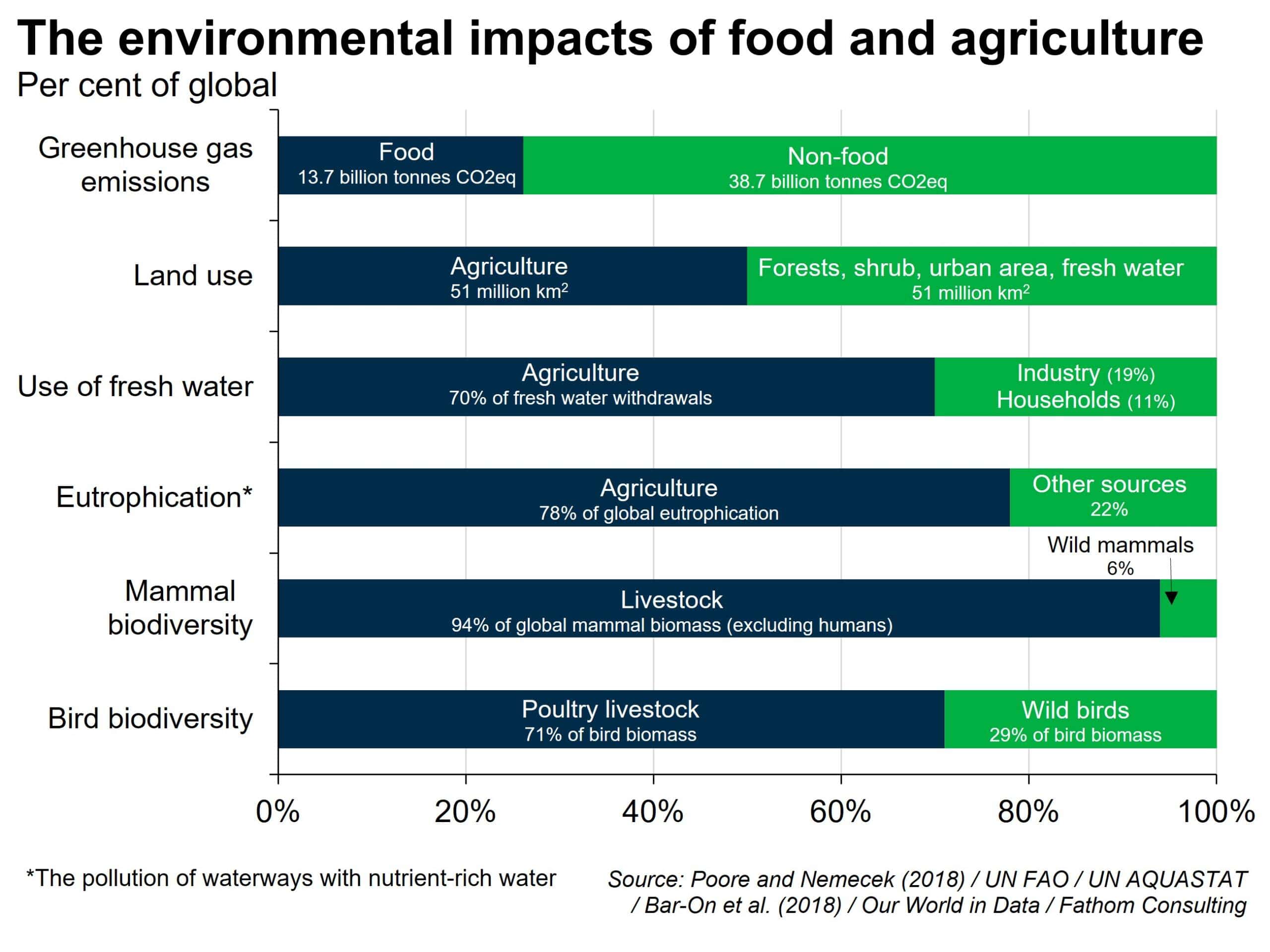

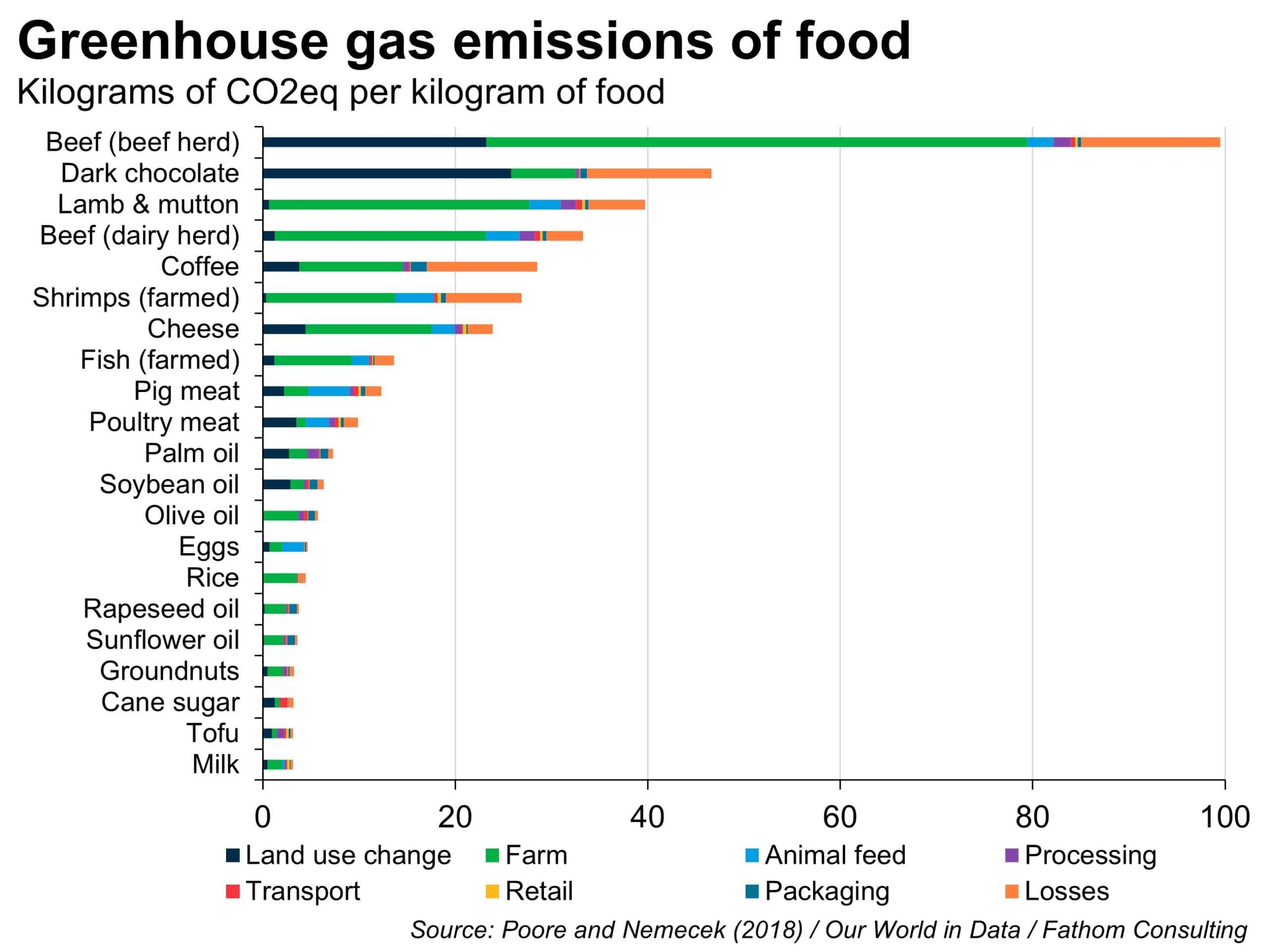

The graphic below provides a snapshot of the environmental impact of food and agriculture. Food production accounts for over a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, the majority of which originate from the farming practices or land use change (for example, deforestation) associated with production. In contrast, all the processes in the supply chain which occur once the food has left the farm (transport, packing or retailing) account for a rather small share of a food product’s total emissions (often less than 10%). This means the ‘eat local’ slogan we often hear touted as the way to reduce the carbon footprint of our diets is somewhat misguided — it’s actually what we eat that is most important, as argued by my former colleague in a previous Fathom blog.

So then, what should the climate-conscious among us be eating? Unless you’ve been living under a rock in the era of what Suella Braverman described as the “tofu-eating wokerati”, I’m sure it will come as no surprise that meat and dairy products tend to emit more greenhouse gases than plant-based foods. Beef is the top offender: producing a kilogram of beef emits a whopping 99 kg of CO2-equivalent emissions, compared to just 3.2 kg per kilogram of tofu. Lamb and mutton, a meat in high demand at this time of year with Christians celebrating Easter Sunday and Muslims celebrating Eid, is the third most environmentally intensive food product, emitting 40 kg of CO2-equivalent emissions per kilogram produced.

But when thinking about the economic impact of our food systems, it is not just the environmental impact to consider. There are also the costs of treating food-related health conditions including malnutrition, diabetes and obesity. Working conditions are stressful and poor for farmers, particularly in developing countries. And increasing food prices put pressure on household budgets, particularly for those on lower incomes. In the UK, food price inflation peaked at 19.1% in March 2023 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted global supply chains and increased energy costs. In a recent study, researchers from the University of Oxford and London School of Economics developed a model to quantify the hidden costs of our food systems. As things stand, the costs of impacts on climate change, human health, nutrition and natural resources, amount to over $10 trillion a year. That is more than the industry contributes to global GDP.

However, there is good news to leave you with (a delightful dessert, perhaps?) as you head into the weekend. By comparing current trends with a transformative approach to food systems,[1] the authors found that adopting the latter could potentially eradicate undernutrition by 2050 and save 174 million lives from premature death caused by diet-related chronic diseases. In addition, food systems could become net carbon sinks by 2040.

One of the most interesting findings from the study was the potential benefits from changing diets alone. Global adoption of a predominantly plant-based diet accounted for around 75% of the total health and environmental benefits in the transformation scenario, and would result in a 2% boost to global GDP per year, on average. What’s more, the projected expense of attaining this transformation through improved policies and practices amounted to only 0.2-0.4% of global GDP per year, a tiny sum compared to the potential multi-trillion-dollar benefits it could generate.

Getting people to change their eating habits is not easy. After all, why should a welfare-maximising meat-lover give up their favourite beef burger today to make future generations better off? Going back to Chang’s chapter on lime, just as lime had to be mandated by the Royal Navy in sailor’s rations to combat scurvy, leaving it up to individuals in the market is unlikely to lead to significant change. Instead, a coordinated approach across governments, public bodies and key stakeholders in the market itself will be crucial in nudging meat enthusiasts towards environmentally friendlier alternatives. Financial incentives, including supporting farmers and businesses transitioning to plant-based food production, and reducing taxes on plant-based products, as well as educational campaigns, are just a few ways in which, together, we can help create a recipe for change. Bon appetit!

[1] Using the MAgPIE modeling framework, which projects how the agriculture and food sector may change over time given a consistent set of socio-economic assumptions and biogeophysical constraints, the authors compared two possible scenarios up to 2050: the “current trends” pathway which represents a continuation of the ‘status quo’ and the “food system transformation” pathway which is defined by a global commitment to achieving an inclusive, health-enhancing, and environmentally sustainable food system.

More by this author