A sideways look at economics

¡Espero que estés bien! Si no, no te preocupes, siempre hay un lado positivo. ¡Es el fin de semana!

J’espère que tu vas bien! Sinon, ne t’inquiète pas, il y a toujours un bon côté des choses. C’est le week-end!

Or for those more like myself, and presently largely constrained to English: I hope you’re doing well! If not, don’t worry there is always a bright side. It’s the weekend!

So, where is this going? Several weeks ago I committed to beginner Spanish classes and, without realising it, I have attended 30 hours of lessons to date. My goal is to at least attain level A1 by the end of this summer, in time for a holiday to southern Spain — where hopefully my efforts will count for something and I may finally get to grips with my nemesis, the rolled ‘r’.

There are many reasons why people choose to learn another language, whether it be for travelling, career, or other aspects, such as family or general intrigue. Mine primarily stem from a desire to communicate with others in their own native tongue rather than coming across as what some may deem a traditional Brit who relies mostly on English.

On the flip side, I can only readily conceive of one drawback to learning a language: the time and effort required in doing so. Or the term economists may often find themselves relating the cost of a number of tasks and activities to — the opportunity cost. This describes the cost of the next best alternative foregone of an action. Or in this case, what’s the most valuable thing I could have done with the time and money (my resources) I have used to learn Spanish? Instead, I could have learnt a different skill, engaged more in different hobbies, spent more time with family and friends, or even just relaxed and bought myself something nice.

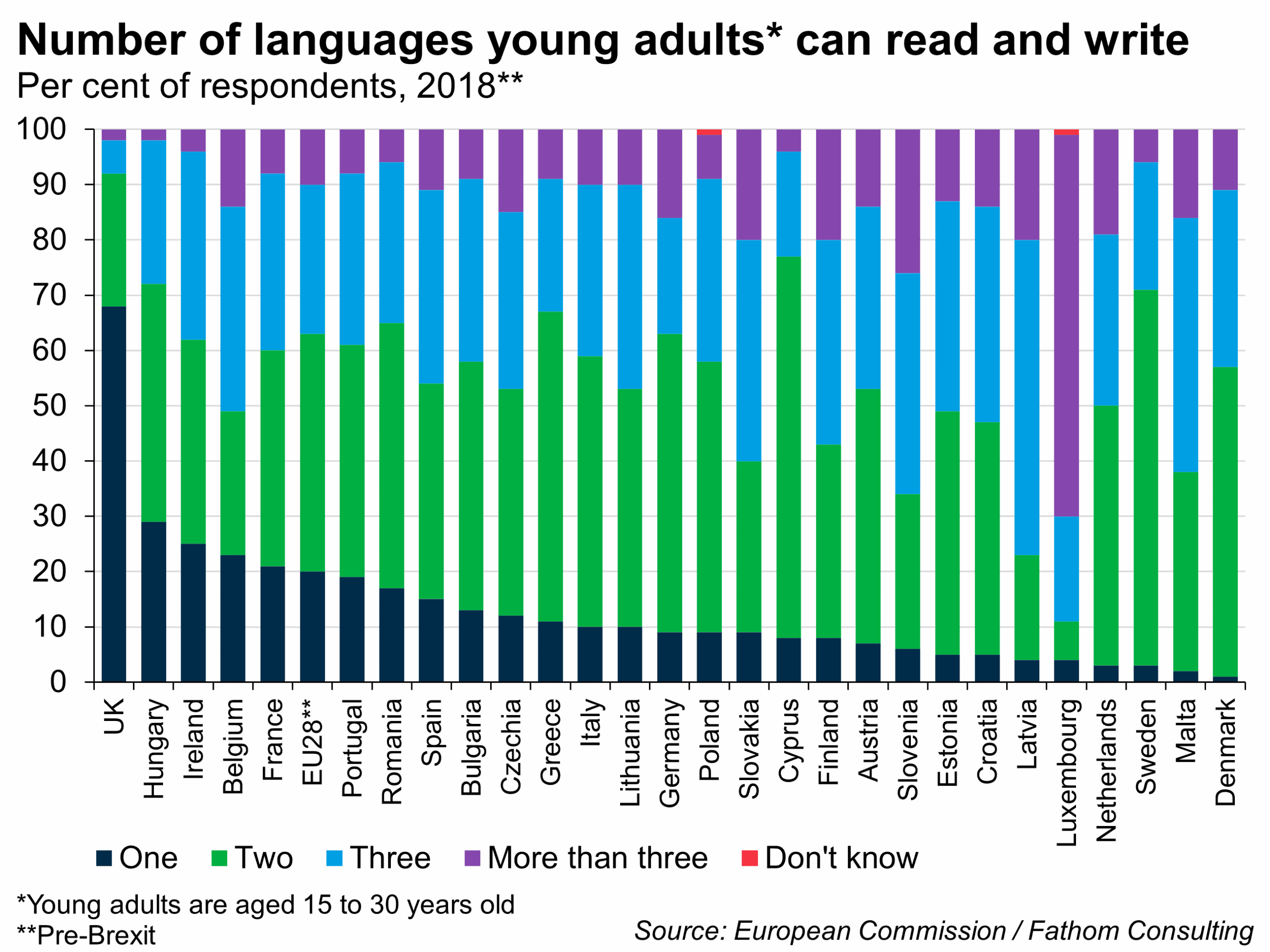

In 2018, compared to the other EU27 countries’ young adults,[1] the UK was found to be markedly limited in its language capabilities. 68% were only able to read and write one language (most likely their mother tongue, English) versus 21%, 15% and 9% in France, Spain and Germany, respectively.

The chart is quite stark in demonstrating the weak relative linguistic capabilities of the UK versus their European counterparts. However, that does not mean it is necessarily an issue. The UK has long been a developed economy without the widespread knowledge of other languages. But, I wonder, would improved language capabilities be beneficial?

The advantages of multilingualism come from greater access to cultures and improved communication capabilities. Meanwhile, language barriers can be perceived as a form of trade barrier and effective tax — reducing trade incentives between parties. Even so, these effects are often more intangible, though several studies have attempted to quantify them. In 2008, a Geneva University research team concluded that Switzerland’s linguistic skills provided an advantage equivalent to 9% GDP. Simultaneously, Ankita Tibrewal found that UK SME’s using language capabilities were 30% more successful in exporting than those who do not. Despite this, the likes of the UK are unlikely to gain as much of an advantage from learning additional languages as Switzerland has, since English is a present-day lingua franca. A RAND Europe study confirms this, finding that an increase in the uptake of another language by ten percentage points could add an additional 0.4%-0.5% to UK GDP over a thirty-year horizon via trade and human capital effects.[2]

The majority of RAND Europe’s estimated boost to GDP comes from the improved human capital of individuals. Personally, I have always been astounded, and in-part jealous, of my multilingual friends with their ease of switching between languages. It also gives them access to jobs requiring additional language capabilities domestically, in the UK, and overseas. This certainly gives them an advantage in job markets and should see them earn higher wages, on average.

Some may say that the need to learn languages, the need for translators and interpreters, is diminishing in the face of ever-improving large language models and AI. Ray-Ban Meta glasses already possess live translation capabilities allowing you to understand French, Italian, Spanish or English, and provide your response translated to the desired language via an app. Meanwhile, a survey by the Society of Authors found that 36% of translators had lost work due to generative AI — demonstrating the feared labour-replacement aspect. Although the leaps and bounds in machine translating capabilities has improved significantly, there continue to be short fallings in the more human element of languages: idioms, metaphors, level of formality, slang and cultural context. For example, the translation of the idiom ‘Bob’s your uncle’ loses its meaning of there you have it, while Japan’s salaryman (サラリーマン) has additional connotations beyond that of a normal office worker/employee which it may be translated to.

It cannot be denied that AI and machine learning models have been hugely beneficial in providing instant access to fairly reliable translations but, in the near future at least, it appears that multilingual skills will still prove useful.

One clear question from all of this is, should the UK be promoting the learning of at least a second language to enhance its ability to communicate with potential trade partners?

Before going any further, it is worth acknowledging that countries face asymmetric incentives to learn a second language. The Anglosphere benefits from English’s status as the prevalent global lingua franca, providing an edge in global communications, academia, culture and media influence — as witnessed with the historic higher success of English-language songs in Eurovision. Much like how the US dollar acts as the dominant reserve currency, a positive feedback loop means that every additional user raises its value. This network effect weakens the incentive of native English speakers to diversify and yet strengthens the incentive of non-native speakers to enhance their English abilities to reap the rewards — further entrenching its status as a ‘global reserve language’. This could explain the significant contrast in multilingualism between the UK and the EU27 countries, seen in the earlier chart.

The UK’s service-oriented economy would likely increase the potential for additional languages to improve access to non-English speaking economies and generate returns beyond that of other economies. However, with English as a leading business language, the UK’s economic status, and the ability to easily hire any desired multilingual individuals from overseas, it is likely not necessary. Nevertheless, it would be beneficial and some intermediate understanding may still aid in occupations where fluency is not required.

Disregarding the economic reasons to learn languages, multilingualism has been linked to staving off Alzheimer’s, mental aging and cognitive decline — with a study finding bilinguals to have experienced the onset of cognitive decline four and a half years later. Aside from this, many link learning another language to having other general upsides in life. So, unless you have more preferred ways to use your time and money, and the opportunity cost is high, why not?

Eso es todo por hoy.

¡Hasta pronto y buen finde!

[1] Young adults, in this instance, are those aged between 15 and 30 years old.

[2] Rand Europe investigated the independent impact of a ten-percentage point increase in uptake at the KS3/KS4 level of four languages: Arabic, Mandarin, French and Spanish.

More by this Author