A sideways look at economics

No, this isn’t about Adele…

No, really, it isn’t…

If that’s what you want, stop reading — you’ll only be disappointed…

Ok, well don’t say I didn’t warn you… This blog is all about Fathom, not Adele. I probably should’ve called it “Hello, it’s us” but the title got you this far, didn’t it? So, please, Go Easy On Me. The rest of this blog has little to do with economics but a lot to do with statistics and a lot to do with Fathom. So, if you’re willing to Hold On for a bit, I’d like to let you know a bit more about us. It should be a bit of light-hearted fun so, All I Ask, is that you stick with it.

21(.95)

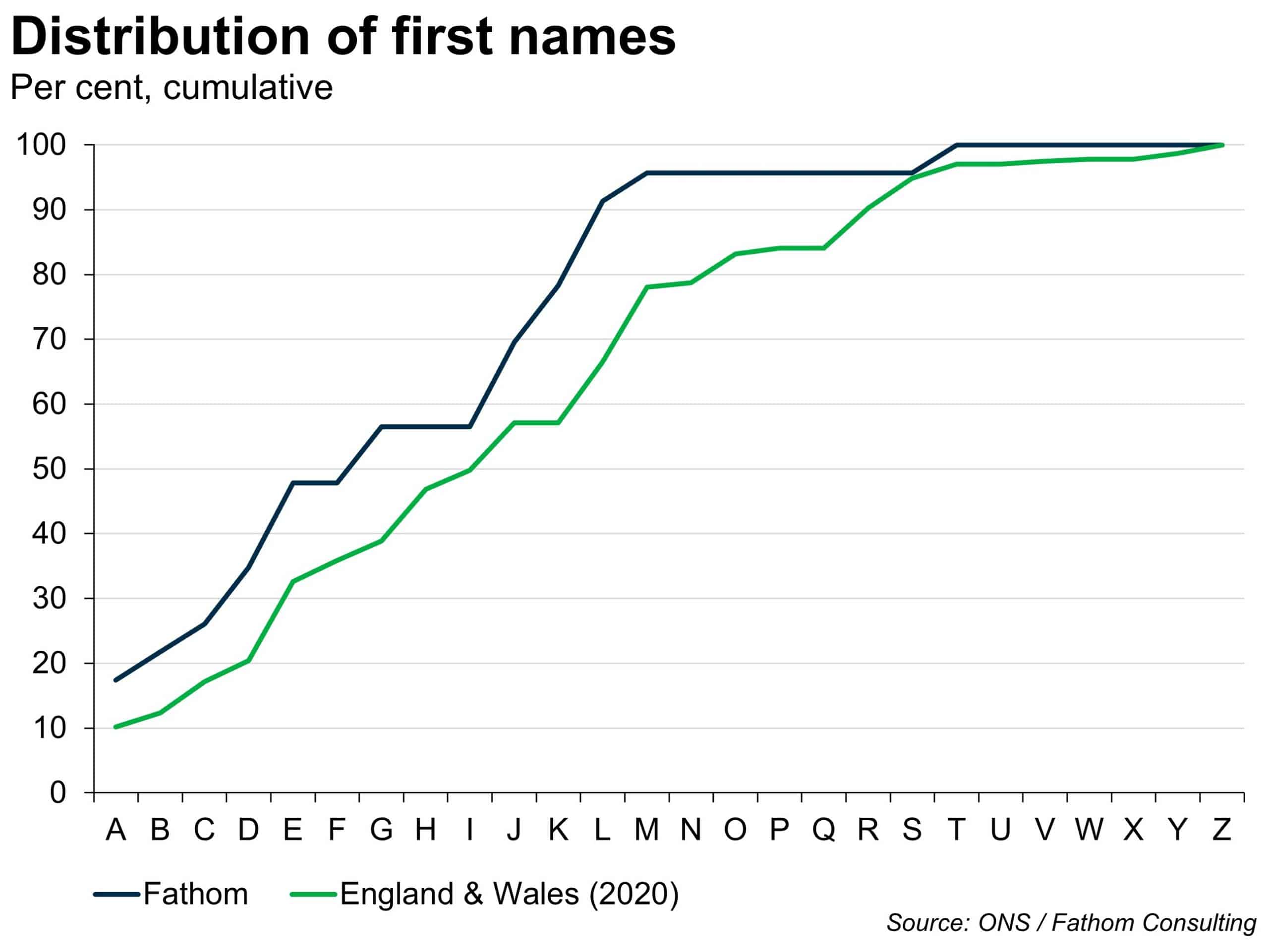

I must confess, I’m a bit of a Daydreamer. Someone Like You may not be, but I am. Thoughts like “do Fathom staff have normal names?” often creep into my head — the answer, if you were wondering, is no! As it turns out, the distribution of first names at Fathom is highly skewed towards the start of the alphabet with only one staff member (Tom) having a name falling in the second half. By contrast, ONS data show that just over 21% of babies born last year had names below ‘M’ in the alphabet. (OK, it’s 21.95% which is really 22%.)

What’s in a name? The results from the literature are a bit mixed (it can be quite hard to separate causality, given names often reflect the socio-economic status of parents). I’m not aware of anything on the impact of the initial of a person’s first name but Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004)[1] do find evidence of racial discrimination in the US labour market and other studies have found evidence of discrimination on the basis of social class.

On a more light-hearted note, Carlson and Conard (2013)[2] find evidence of an effect of last names. Specifically, they find that those with names towards the end of the alphabet tend to be more impulsive shoppers. Andrea Zazzarelli, our Technical Director, insists he’s not but his wife claims that he is and that “he creates himself fake needs to buy s***”.

23

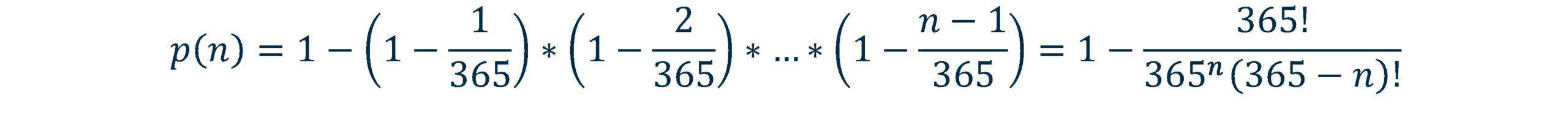

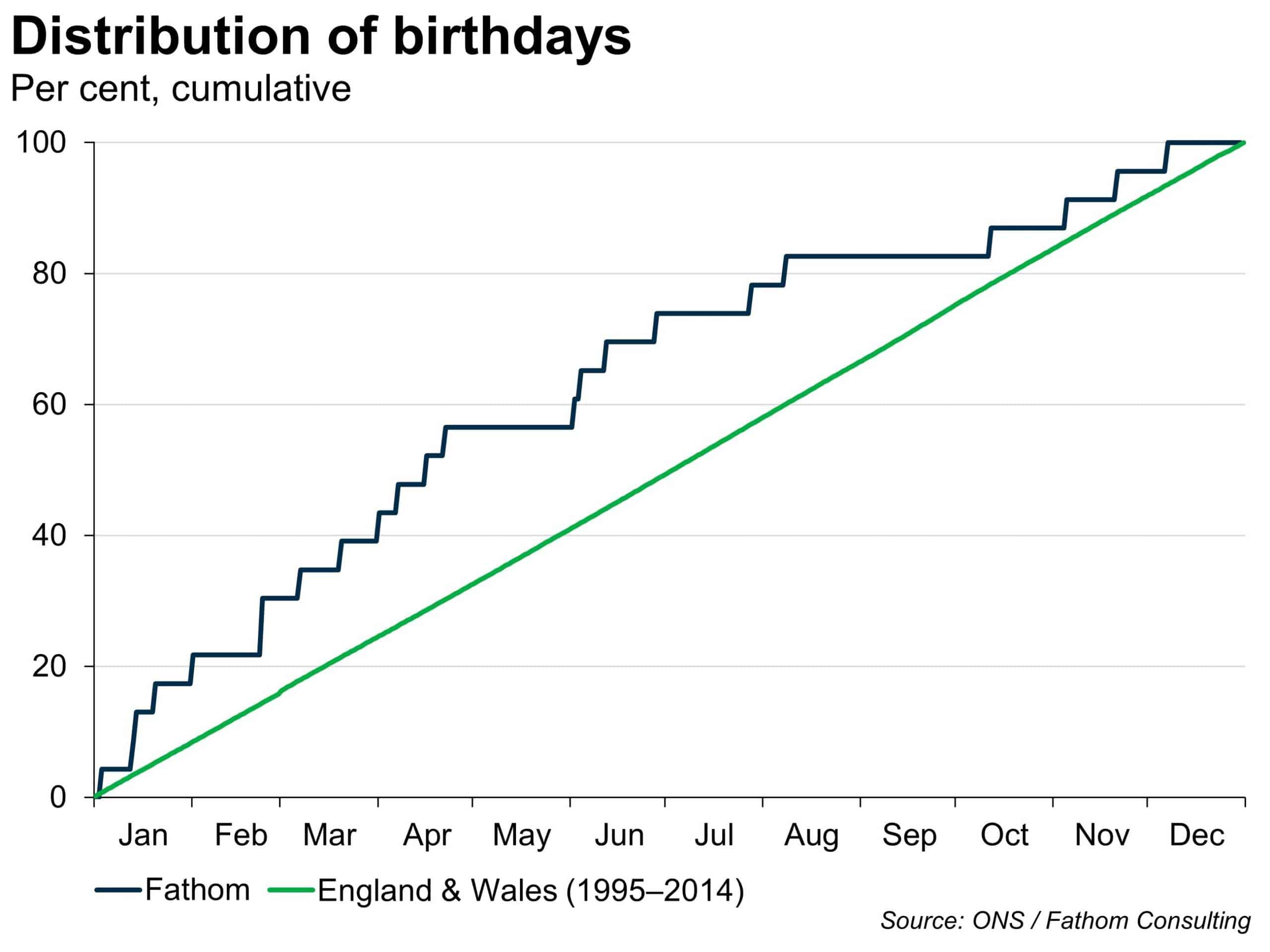

23 is the key number when it comes to the birthdays. (Sorry, I tried to work 25 in, but it just wasn’t possible.) Put simply, the ‘birthday paradox’ states that, if you put 23 people in a room then, more likely than not, two of them will share a birthday. Don’t believe me? Look it up! The formula for this is shown below:

Complicated, huh? Well, I’ve got a Remedy for that — just look at the chart below. It traces out the probability of at least one shared birthday for different sized groups of people. As you can see, it rises surprisingly quickly, hitting 50% with 23 people and nearly 100% with 70. Interestingly, Fathom currently has 23 staff members, and we also have one shared birthday!

30

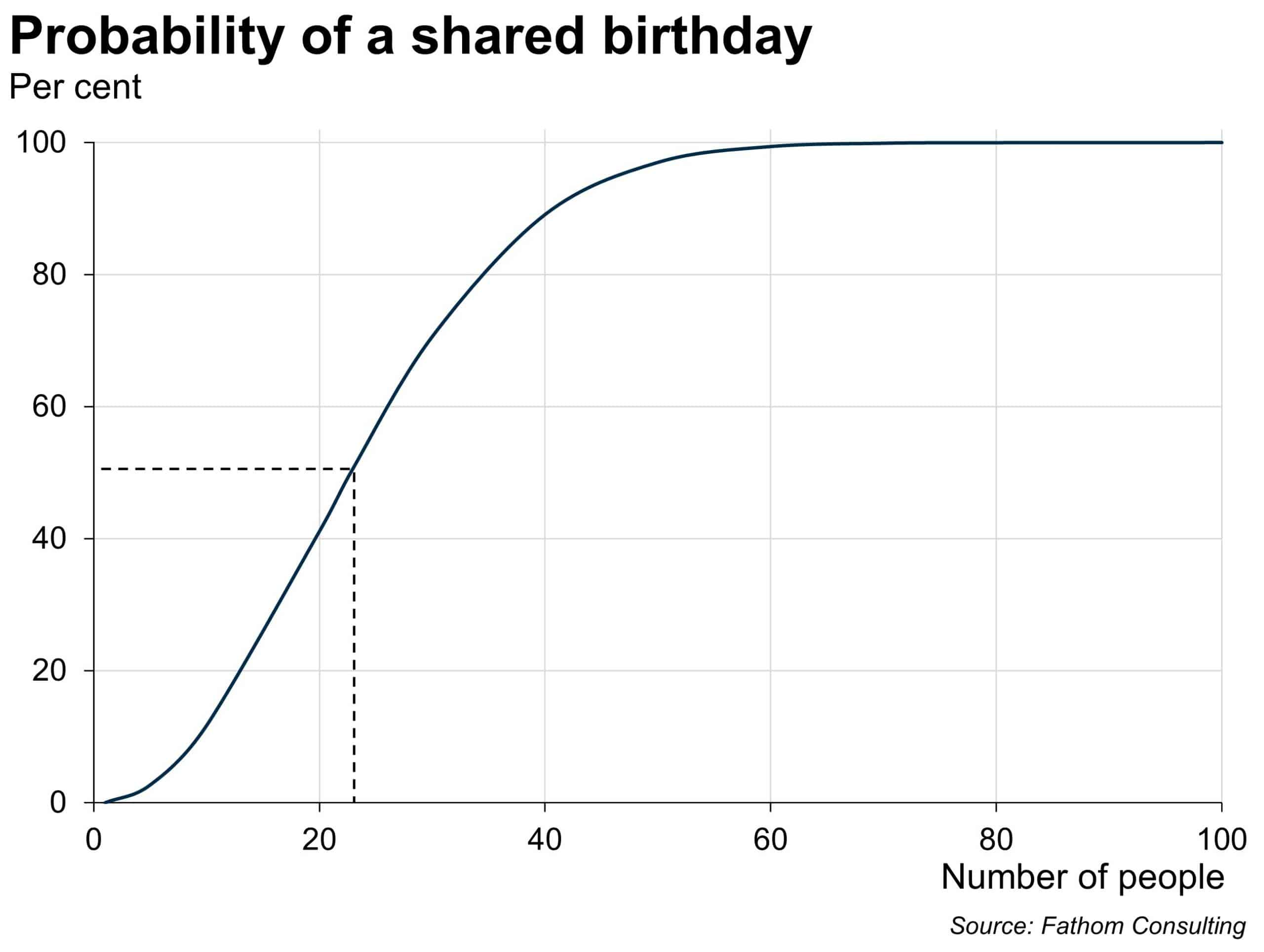

Of course, the birthday paradox assumes that birthdays are independently distributed across the year which, to a first approximation across England and Wales, they are. However, this does not seem to be the case among Fathom’s staff. Indeed, 30% of our collective birthdays fall within the first two months of the year, with three-quarters occurring by the end of July. For England and Wales as a whole, those numbers would be 16% and 58% respectively. Clearly, we’re ahead of the curve…

Actually, funny thing is that we’re not… A well-documented finding from the literature on education is that children born earlier in the academic year (which begins in September in the UK), tend to achieve stronger academic outcomes. This so-called ‘relative age effect’ implies that the lack of Fathom births in September would have counted against us When We Were Young. However, that’s a Million Years Ago and, generally speaking, the effect is found to shrink with time. (Some, such as Larsen and Solli [2017],[3] actually find that this effect may even go into reverse in older age.) So, by now, that should all be Water Under the Bridge. As an interesting aside, this relative age effect is also found to exist in sport with a disproportionate number of footballers found to be born just after the cut-off for age groupings.

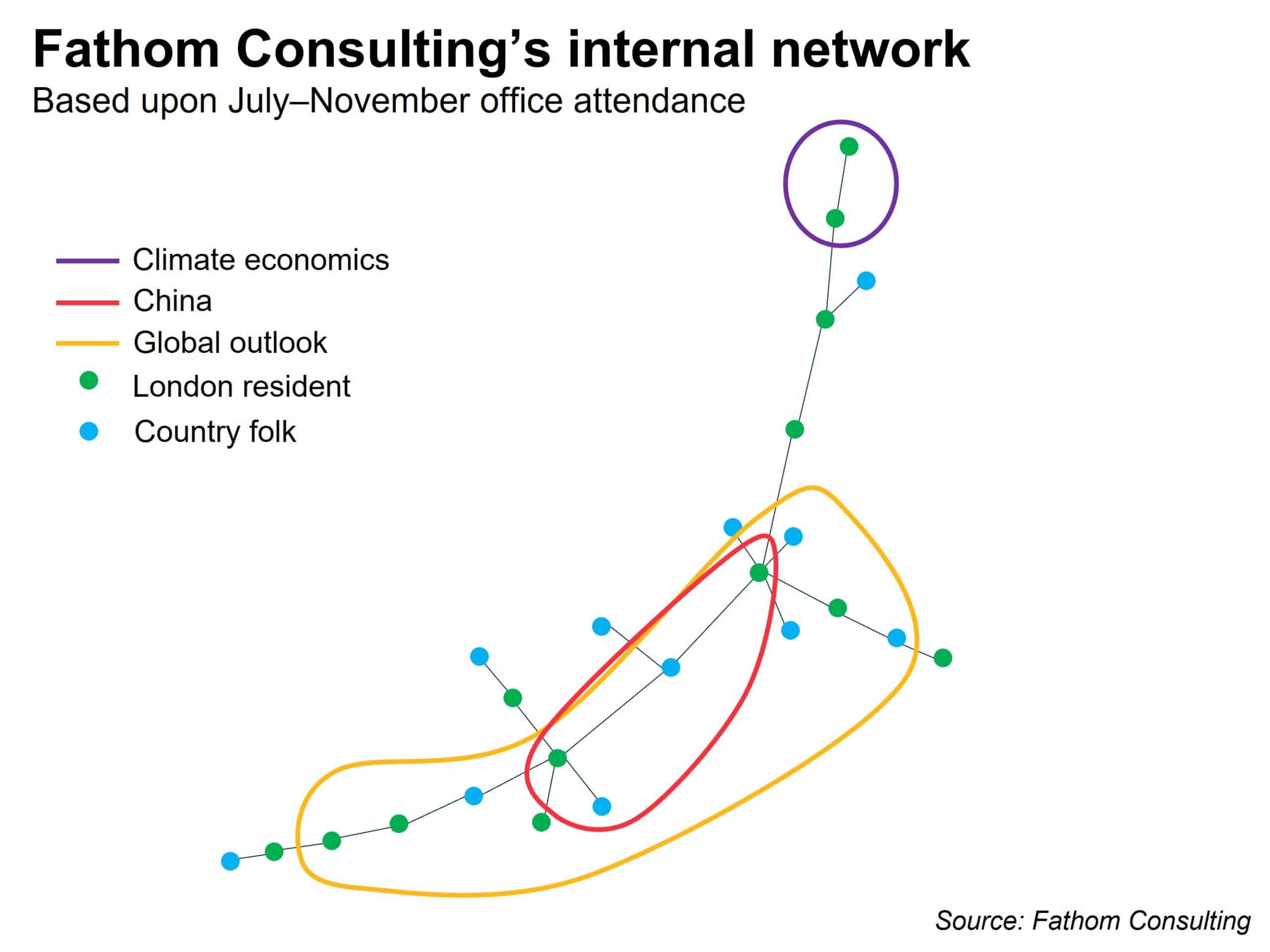

Saving the Best For Last, I’d like to leave you with a little insight into our working patterns. Like many companies, we’ve now moved towards more flexible working arrangements with staff typically attending the office two to three days per week. Below, you can see a minimum spanning tree reflecting the correlations in office attendance since July. From this, it’s possible to identify clusters consistent with Fathom core areas of expertise — climate economics, China, and the global outlook. But, more than just that, it’s possible to identify the different lifestyle choices of our staff. For instance, light blue nodes reflect staff living outside London who often attend the office on a week-on/week-off basis. Note how these individuals typically lie close to the edges.

What does the literature say about working from home? Well, Rumour Has It that we wrote about this last year! Don’t You Remember? In short, evidence from studies such as Bloom (2015)[4] find benefits in terms of increased productivity, job satisfaction and improved employee retention. While the truth is probably not quite as clear cut as the paper suggests, it does seem that WFH is, on balance, a net positive thing.

Anyway, that’s enough about us. I hope you’ve learnt a little bit about Fathom and maybe picked up some interesting little titbits along the way. It’s Friday afternoon and, as I’m sure you know, we’re about to sign off for our traditional beer o’clock. That said, something you should know is that it’s not always about beer. Sometimes, I Drink Wine.

[1] Bertrand, Marianne, and Mullainathan, Sendhil (2004), ‘Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination’, American Economic Review, 94 (4), pp. 991-1013.

[2] Carlson, Kurt A. and Conard, Jacqueline (20130, T’he Last Name Effect: How Last Name Influences Acquisition Timing’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2011, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2264918

[3] Larsen, Erling R. and Solli, Ingeborg F. (2017),’ Born to run behind? Persisting birth month effects on earnings’, Labour Economics,46, pp.200-210.

[4] Bloom, Nicholas, Liang, James, Roberts, John and Ying, Zhichun J. (2015), ‘Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 130, pp. 165-218.