A sideways look at economics

I count myself extremely lucky. Not only am I one month into an excellent new job as an economist at Fathom Consulting, but — drumroll, please — last week I secured a launch day PlayStation 5. The rollout of the next generation of games consoles from Sony and Microsoft has not passed off entirely smoothly and has provoked plenty of controversy. With reports of scalpers pushing up prices to exorbitant levels on the secondary market,[1] and some customers receiving deliveries of cat food or kitchen appliances[2] instead of their eagerly awaited console, I feel very fortunate that mine arrived with barely a hitch.

The reason that the launch of the next generation of both PlayStation and Xbox consoles has been so fraught with controversy is that supply simply can’t keep up with demand. The COVID-19 pandemic has obviously had a major impact on both the supply and demand sides, but other factors are also at work. Let us take a deeper look.

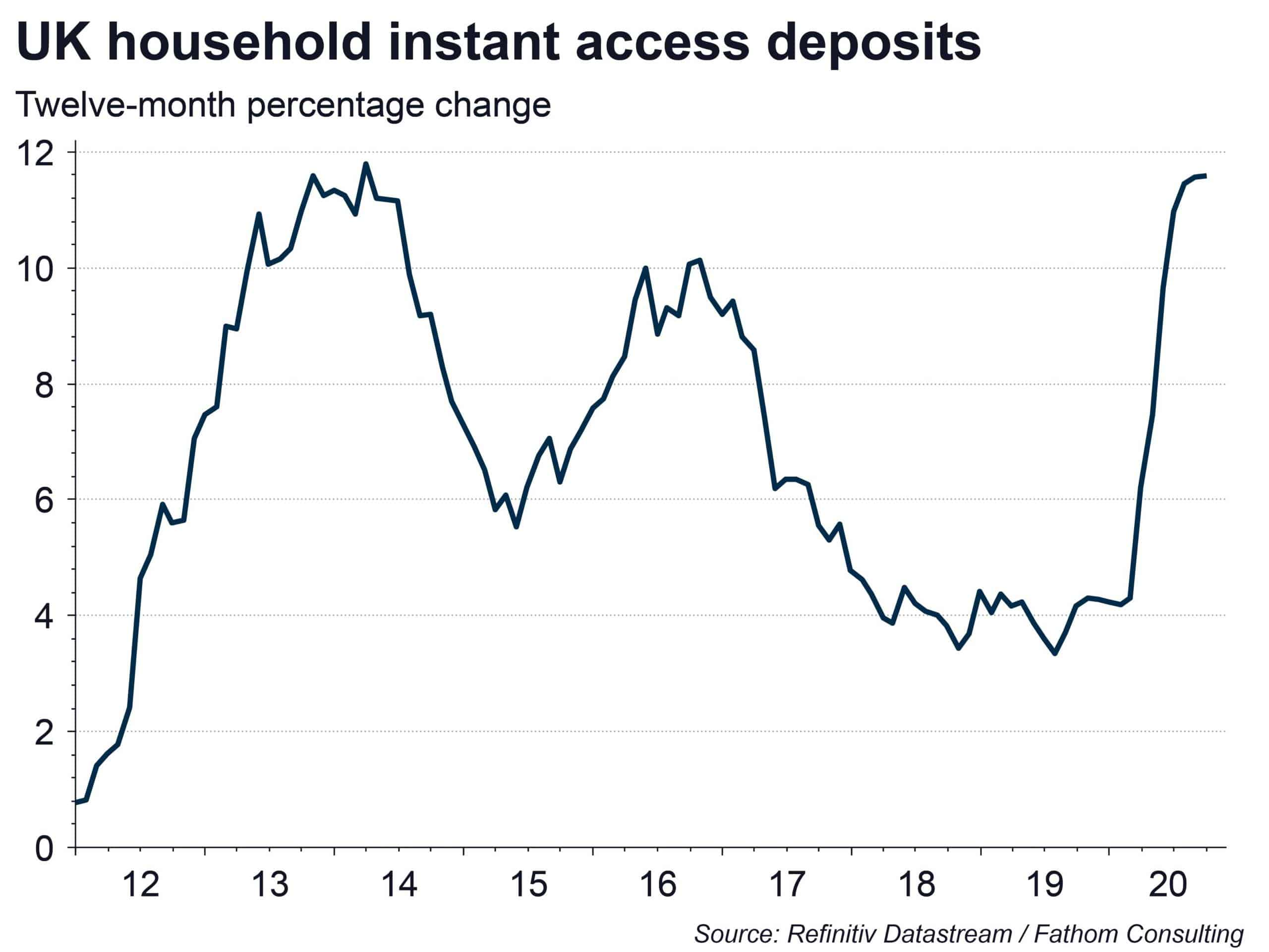

Over the course of 2020, households have increased their savings and dramatically pulled back on discretionary spending. In the UK, liquid money has been growing at 11.5% over the course of the year, close to series highs. For me, not going to a pub on a weekly basis has done wonders for my bank account. And with more liquidity out there (although less of the alcoholic kind, for me at least), and more time on peoples’ hands, more people were likely to have the means and the motive to afford a new PlayStation or Xbox.

Added to this, both consoles are priced competitively. With previous console generation launches, the price and pre-orders have been announced at the major annual summer gaming convention, the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3). Microsoft “lost” in the last round of console releases, in 2013, initially pricing their Xbox One console significantly higher than Sony’s PlayStation 4 when both were announced at E3. It was a tactical mistake that Sony has been careful to avoid. Back in 1995, when announcing the original PlayStation and knowing that their competitor, the Sega Saturn, was going to be priced at $399, Sony’s Steve Race took to the E3 press event stage to say just three words: “two-ninety-nine”.

This year’s E3 was set to be held in June but was cancelled as a result of the pandemic, causing both Microsoft and Sony to delay announcing the pricing of their new consoles. Each apparently waited for the other to announce first. The speculation was that consoles would be priced around $700, which is still cheaper than an equivalent spec gaming PC. Microsoft caved first, announcing a competitive price of $499 (£449) for their Xbox Series X on 8 September which Sony could only match. And despite stronger demand, neither is likely to hike retail prices to a market-clearing value, due to the damage it would cause to their reputation and their ongoing revenues. For both, it’s sales of games and gaming subscriptions that ultimately bring in profits, rather than hardware. If you want the latest Call of Duty game with all the bells and whistles, that’ll be £90. So, by getting the platform into as many customers’ hands as possible, both companies maximise the base which they can later monetise.

So, how well have Sony and Microsoft done at fulfilling demand, and what obstacles have they come across? On the supply side, the main components of both consoles are the silicon chipsets inside each respective console. The processors and graphics powering both consoles have been specially designed by AMD, an American technology company. But production of those chipsets is carried out by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

Taiwan has been relatively unscathed by the COVID-19 pandemic, with total cases around 4.5 per thousand people. No major government restrictions were put in place, although international travel between certain countries has been restricted, and track-and-trace measures put in place for those that do travel.

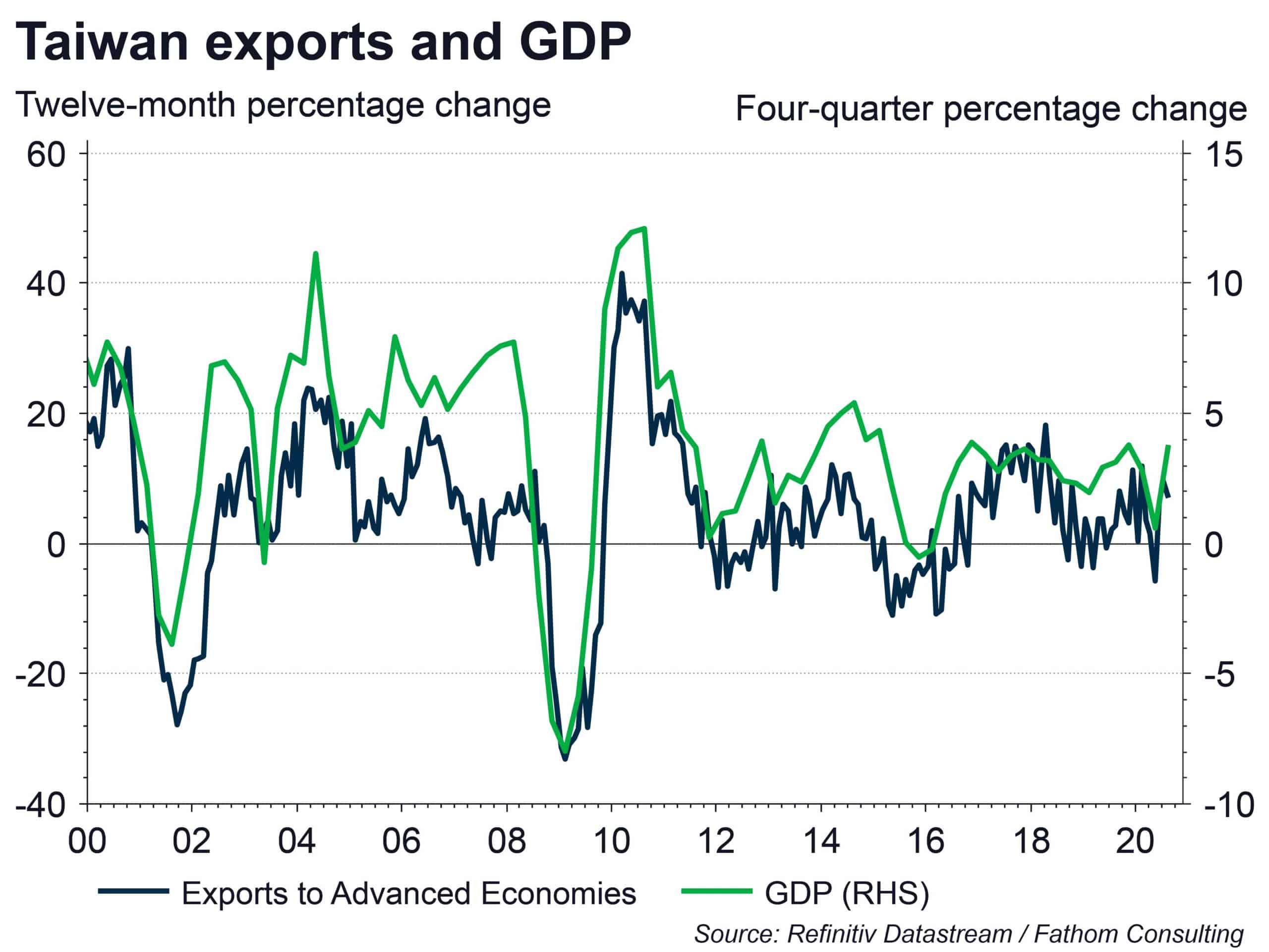

Despite this, Taiwan’s GDP growth turned negative in 2020 Q2 alongside weaker outturns for exports. Its economy is predominantly export-driven, focusing on demand from advanced economies. Although exports have picked up in Q3, using this as a proxy for likely semiconductor manufacturing performance, 2020 is set to be a weaker year overall for both manufacturing and growth.

While no retailers are confirming exact availability, with likely difficulties in the supply chain, speculation is high that volumes of both consoles are particularly low. And with demand higher than initially expected, it is unsurprising that pre-orders of both consoles sold out globally almost instantly on launch.

So if you’re looking for a new console for yourself or a Christmas gift this year, I wish you the best of luck finding one that’s not going for twice its value on eBay. The unique chain of circumstances created by COVID mean that it may be mid-2021 before enough consoles make it to market to satisfy demand.

[1] One Playstation was auctioned up to £10,000 on eBay, according to reports https://www.thesixthaxis.com/2020/11/20/ps5-where-to-buy-uk-stock-scalpers/

[2] Amazon has acknowledged problems with its Playstation deliveries, after numerous customers reported receiving random items or nothing at all https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2020-11-20-amazon-playstation-5-customers-report-receiving-toys-kitchen-appliances-instead