A sideways look at economics

This August I turned 40 and while I’ve cherished the abnormal levels of attention and celebrations, I’ve so far remained immune to most symptoms of a mid-life crisis. I have no urge to purchase a sports car or motorbike or a trophy wife. I see sport as a necessary evil enabling and counterbalancing a relatively carefree lifestyle on my terms, not on those fuelled by bucket lists, age-related insecurities or peer pressure. As a result, I feel no desire to compete in a marathon, and find a match of beer pong time better spent than a round of golf. However, the one stereotype of middle age to which I’m partial is wine. Together with economics, wine is possibly the only other aspect of my life where curiosity feeds on itself. With both, I often end up more confused than I started off, but always happy to go back for more. As a learning experience, obviously.

Wine has also been a steady companion on a journey of self-discovery, chiming with various aspects of my life. For example, I wanted to immortalise the birth of my son with a picture that gave an objective idea of how tiny he was. The objective measurement unit was a bottle of Italian wine that I put next to him in his cot. For my holidays in Italy, I’m regularly drawn to an area known as Cilento which was inhabited in ancient times by the Oenotrians, whose name translates from ancient Greek as ‘the people from the land of vines’. Past family holidays in Australia and South Africa were a lot less about the wildlife and nature and much more about wine tasting and often both together. When my wife enthusiastically asked what I wanted to do for my 40th birthday, my reply of: ‘les vendanges’ was met by a deflated look. I’m due to kick them off next week in Burgundy with a friend in my European adaptation of Sideways (in Paul Giamatti’s role of Miles, obviously). I feel that wine and I also have a lot in common: quality improves with age (but also age is no substitute for quality), taste is a much better appraisal method than price, and never judge a bottle by its label, are just three of the more obvious examples. More broadly, it would not be an exaggeration to affirm that wine is the fermented essence of human nature, the perfect accompaniment to the threads of western history and a generous pouring of the social in social sciences.

For example, a number of great military leaders were renowned wine lovers: Alexander the Great and Mark Antony in ancient history and more recently Winston Churchill and Napoleon who once said “in victory, you deserve Champagne. In defeat, you need it”. The course of North American history might have also been very different if for example the French troops had not allegedly been caught by the English having over-imbibed at the climax of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec City in 1759.

In politics, wine diplomacy is a real thing. In the UK, a committee selects and rates the wines in the state collection to be served at official functions and banquets depending on who the guest is. I have no doubt that the only dark truth about the many secretive gatherings of world elites is that they are fuelled much more by a taste for good wine than by Bond villain, world-conquering conspiracies. This is nothing new, as no self-respecting Greek or Roman high-flyer would ever dream of throwing an exclusive symposium or convivium without copious amounts of wine for his esteemed guests. There is at least one of these modern meetings that makes no pretence about doing so. The gathering at Camp Kotok in the US is an invitation-only event where the entry price is a case (or two) of wine of choice. I’m pleased, and not surprised, to say that it’s a gathering of mostly economists and economics lovers. For any readers with a spare invitation to the next get-together, I’d be very glad to contribute to the stimulation of collective brain waves with my own case of wine.

Personal agendas aside, there are many lessons that economics professionals can learn from wine. I could simply point to the existence of the American Association of Wine Economists with its own journal, a prolific roster of working papers and significantly more interesting meeting agendas. In a more poignant example, England kept sky-high tariffs on (French) wine even after the repeal of the Corn Laws in the 1840s (60–80% until the late 1850s), casting doubts on the credentials of the English as champions of free trade. English tariffs on French wine dated back as far as the late 17th century when England halted trade with France as a result of the Nine Years’ War. Wine accounted for a staggering 20% of British imports from France and had a profoundly distortionary impact on society and economies. For a start, reduced access to wine through price controls goes a long way to explaining the dominant English taste for beer, and the notion of wine as a marker of social stratification. (Notably wine tariffs were levied on a volume basis, not ad valorem, essentially ensuring that upper class cellars would stay well stocked up with expensive clarets.) British wine tariffs also altered the patterns of European trade, transforming economies like Portugal which was never too successful at selling wine to other countries prior to the 20th century and had actually signed a treaty in 1705 allowing its prized asset to enter England at a tariff of no more than two-thirds of that of other nations. Swap wine with 5G technology, Portugal with Vietnam and the parallels with some current affairs appear intriguing even without uncorking another bottle of wine.

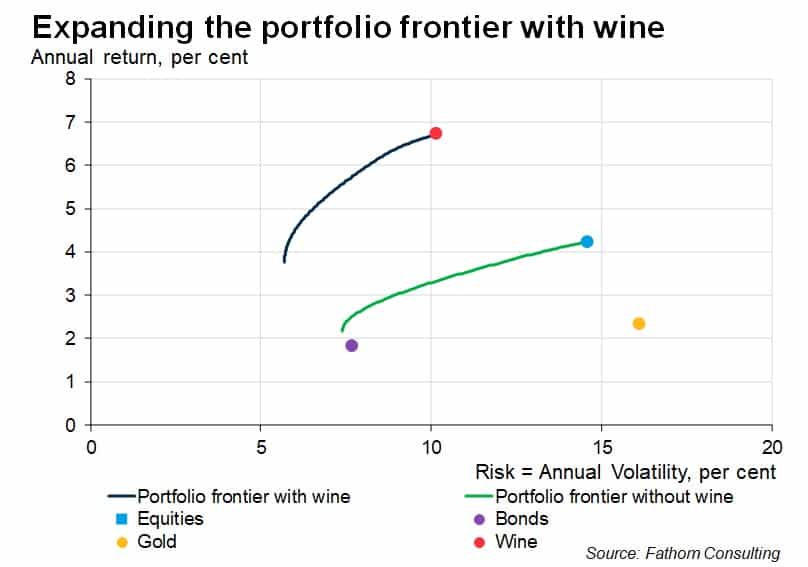

Finally, it would be rude to leave the reader hanging without extolling the virtues of wine from a financial and asset allocation perspective. First, an anecdote: as a young analyst in 2006/07 I became fascinated with the meteoric rise of asset-backed securities. I need to thank wine again for providing a sobering perspective on some of the assumptions and difficulties underpinning the valuations of these assets ahead of the crisis. During the boom years, one of the very few defaults was a French ABS deal backed by vintage wine bottles that ended up in pieces. An early allegory of the glass-like fragility of the financial system. Since then, the rise of wine as a financial asset has steadily increased, leading to the creation of specialist asset managers, fine wine benchmarks and broader ‘passion’ indices such as the Coutts one that we help produce. As an experiment worthy of this blog, I’ve taken the Liv-ex fine wine investable index at face value and added it to a portfolio containing global equities, bonds and gold. I then solved for the most efficient portfolio suggesting a healthy 58% allocation to wine and a much better risk-return profile than any portfolios excluding it. This experiment shows that adding wine truly expands your frontier, though I would recommend doing so the old-fashioned way to preserve the social aspect of wine and avoid the risk of a truly amazing bottle ever turning sour.