A sideways look at economics

Following on from last week’s TFiF, I’m also using a recent trip abroad as a hook. However, my trip wasn’t a regular holiday, but a one-year unpaid sabbatical, during which I travelled the world. This got me thinking about the costs and benefits of sabbaticals — something I probably should have considered before I decided to take one. Here’s what the literature has to say.

Sabbaticals come in all forms, both in terms of length and substance. Although they’ve been gaining traction in the corporate world, they’re still far less common than in the academic world, where they’re well established. Traditionally, academic staff were granted a sabbatical once every seven years. Indeed, the term ‘sabbatical’ has its roots in the word ‘sabbath’, which according to the Book of Exodus is a day of rest on the seventh day.

Academic studies on the merits of a sabbatical are few and tend to focus on the academic world, where sabbaticals are usually paid and don’t represent a complete break from work. Furthermore, due to their reliance on small sample sizes and subjective self-reporting the results of these studies have to be taken with a pinch of salt.

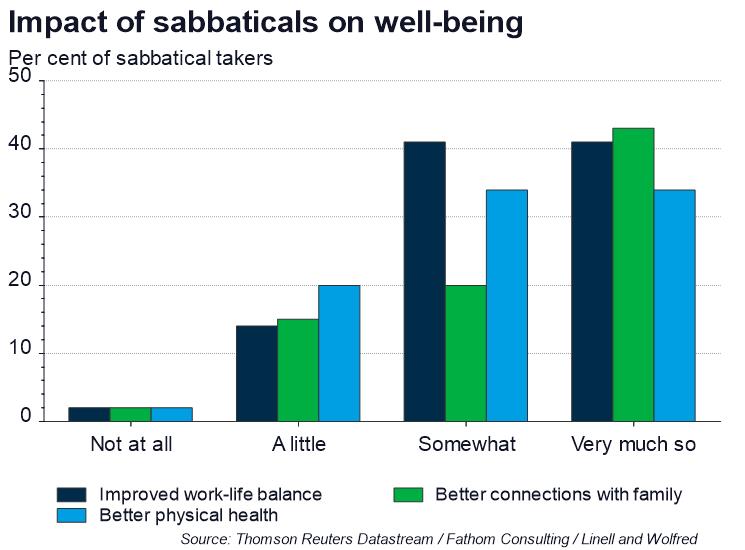

This notwithstanding, sabbaticals are cited[1] as improving employees’ overall well-being, both mentally and physically, by restoring the work–life balance and improving connections with family. No surprises here. But sabbatical returnees are also found to have an improved perspective and/or attitude, and enhanced knowledge and skills.

Arguably more surprising, sabbaticals are also associated with benefits for the employer[2] — you’re welcome, Fathom. Specifically, they’re credited with improved loyalty and morale. Healthier, more motivated and committed employees will work harder and be more productive.

Companies are also found to benefit from the enhanced skills of those employees left behind. The disruption caused by an employee taking a sabbatical, especially if that employee is relatively senior, might force other, more junior, staff, to step up. Thereby equipping the replacement staff with new skills and experience that are useful for organisational succession planning.

Far from going on a sabbatical, nearly a quarter of Americans haven’t even taken a vacation in more than a year.[3] More than half of American employees reported having unused vacation days in 2017, accumulating 705 million unused days, 212 million of which they forfeited. The most reported barrier to taking all their vacation time was a concern that they would appear to be less dedicated, or even replaceable.

This concern seems to be ill-founded. Employees who forfeit their vacation days don’t perform as well as those who use all their time. Forfeiters are less likely than non-forfeiters to have been promoted within the previous year and to have received a raise or bonus in the last three years. Employees who miss out on vacation days are, instead, generally rewarded with more stress. Workers who forfeit vacation days report that they’re more stressed about work than those who take all their annual leave. The question of how much leave workers should take was covered by one of my colleagues in an earlier blog.

An anecdote from Stephen R. Covey’s book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People springs to mind:

One day, you meet a man in a wood who is feverishly trying to saw down a tree.

He looks exhausted, so you ask him how long it has taken so far. “Five hours,” he replies.

“And it’s hard work!”

You then ask him why he doesn’t take a break for a few minutes and sharpen his saw, as this would help him to cut more quickly.

“I don’t have time to sharpen the saw,” the man replies, “I’m too busy sawing.”

It also seems to be important how you spend your vacation. Americans who use most of their vacation to go travelling not only seem to be happier and healthier, but also more successful than those who stay at home. Travellers report a higher likelihood of receiving a raise, bonus, or both than non-travellers.

Correlation doesn’t imply causation, but I’m still tempted to take these results at face value. So, having just become more productive, benefited my co-workers and company, and having spent the equivalent of ten times my annual leave travelling, I anticipate my upcoming raise, bonus, or both. In the meantime, I’ll be looking into the benefits of a second sabbatical.

[1] Deborah S. Linnell and Tim Wolfred, ‘Creative Disruption – Sabbaticals for Capacity Building & Leadership Development in the Nonprofit Sector’.

[2] Rachel Clark McDearmid, ‘Time Out and Time Off: A Systematic Review of the Benefits of Sabbatical’, UPEI School of Business, 2014.

[3] Project Time Off, ‘State of American Vacation 2018’.