A sideways look at economics

I’m not planning to glue myself to a tube carriage. And I’m not planning to wheel a pink boat down Oxford Street. But I did recently take an incredibly eco-friendly action: I said on Facebook that I am committed to doing something for the climate. Of course, actually doing something would be good too, so I made a private commitment to do that and set out to take a holiday without getting on a plane; not a Greta-Thunberg-sail-across-the-Atlantic-style effort, but more of a person gets on a train kind of vibe. My upcoming travel requirements are within Europe after all, from London to Klaipeda (Lithuania) and back, although my bubble soon burst after a few hours of research which revealed that I had a choice between six days of travelling using trains and buses, costing more than £500 per person or two two-and-a-half-hour flights for less than half of the price. I booked the flights.

Admittedly, this is an epic fail on my first attempt to fulfil my private pledge to actually do something to reduce my carbon footprint.[1] Sad, but there are a few silver linings. First, I have learnt some useful things by doing this research, including how to calculate my carbon footprint. Second, a high-speed train linking Poland and Helsinki, via Lithuania, is set to open in a few years, which will trim a day off the journey time either way and make doing that trip cleaner. Third, it turns out that I was right in the discussion we had, when my wife equated (in terms of their environmental impact) my leaving the bedside table lamp on when I’m not in the room, to us flying to and from Lithuania. I’ve now learnt, and ‘pointed out’, that the CO2 emissions generated from heating and lighting our home for an entire year are less than those that will be generated by us flying to and from Lithuania.

Readers may not be that interested in my domestic squabbles, my own climate activism (or lack of) and train infrastructure in Eastern Europe. They might, however, be interested to hear about carbon footprint calculations and my reflections from having done so. If so, read on.

There are several tools which allow you to calculate your carbon footprint, which ask about your lifestyle, including where you live, how you travel, your consumption and eating habits. I would strongly encourage everyone to do it. There is a climate emergency unfolding so it seems sensible for us to have an idea about how we contribute to the problem, and which aspects of our lifestyles contribute the most. I can imagine that before long we will all be required to do this by law, just like we complete our tax returns. I used carbonfootprint.com, which estimates how much CO2 each bit of your consumption generates. It can take several hours to do this, which makes it the sort of thing that you typically do another day, when you have more time. But in other ways it’s fun: it’s easy to see how much carbon a particular flight would emit, compare the emission intensity of different cars and how much difference it would make if you stopped eating meat and became vegan.

As our managing director Erik Britton highlighted in an excellent TFiF a few months back, government policy is needed to tackle the climate emergency. He’s spot on with that point, but I would stress that actions by individuals are important too. If I change my habits and reduce my carbon footprint, but nobody else in the world does, nothing changes at the macro level. If I change my consumption patterns and this TFiF convinces one other person to make changes to their lives, this still doesn’t make a difference. But if that person convinces another person, and that person convinces another person, and this continues, at some point this will make a difference at the macro level. If people believe in something, and I believe many people do when it comes to the environment, that point might not be as far away as you might think. And if enough people believe something, it will force even the most self-interested of governments to change their policies too. Welcome to trickle up economics.

Economics has been described as the study of how to satisfy unlimited desires with limited means, and this question should be at the heart of thinking about the climate emergency. To use economist jargon, we are faced with a constrained optimisation problem: we want to maximise something (i.e. consumption, GDP or our unlimited desires) but we have a constraint in doing so (i.e. a certain level of carbon emissions, beyond which the planet heats). We can develop models to help us figure out the best way to do this, at both the macro level and micro level. But we don’t need a model to tell us the simple truth: if we want to halt (or dare I say reverse) global warming, we need to cut back on the activities that are responsible for generating the most carbon emissions and replace them with activities that have a lighter footprint.

Government policy can help to achieve these goals through taxing of carbon intensive activities (which basically means making individuals and businesses pay for the negative externalities that their activities cause), while investing in the infrastructure that can help individuals and businesses reduce their carbon footprints. They could also embrace some of the lessons taught to us by Nobel prize winner Richard Thaler in his book Nudge, which shows how indirect suggestions and the way things are framed can influence human behaviour. For example, by making us opt out of paying into a pension scheme, far more people now pay into their pensions. Governments could make us opt out of paying for the emissions that our activity generates. Not only would that force us identify how much we generate (which I imagine would lead us to cut down on these activities), but it would raise revenue which could be used to fund low-emission-enabling infrastructure or emission offset projects. It’s not straight forward, but it is an idea that should be explored.

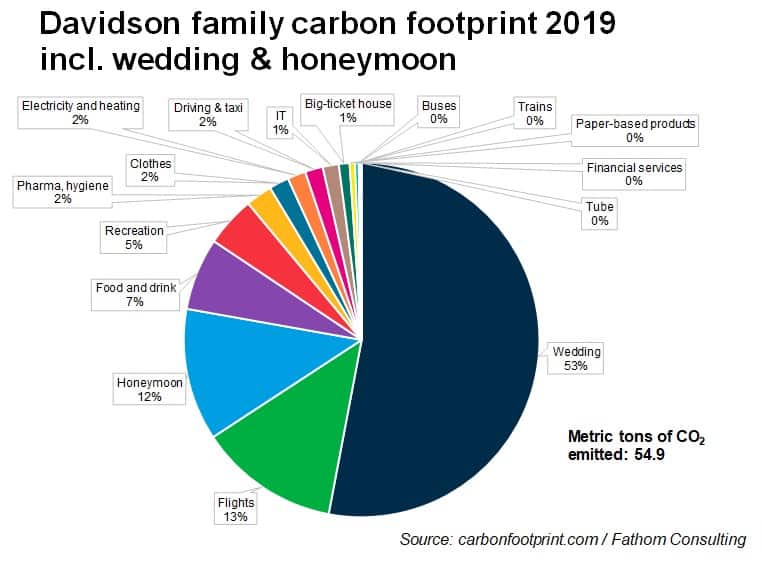

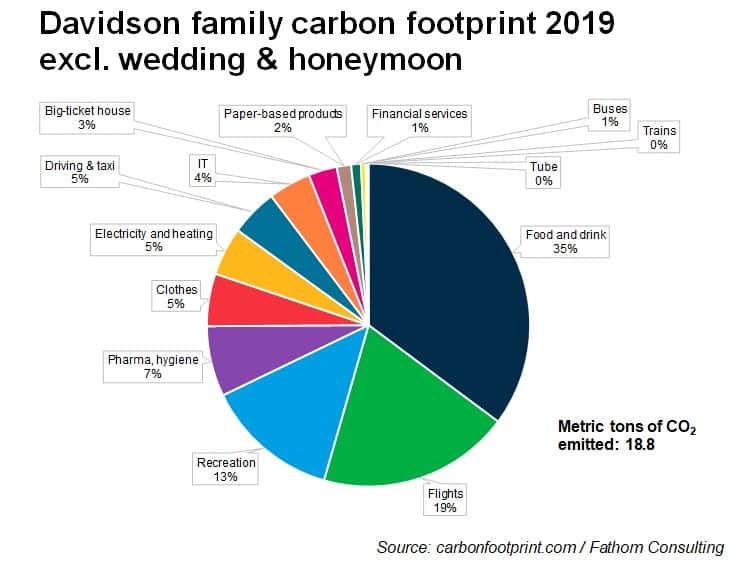

Arguably, the most important step to us reducing our emissions is understanding the externalities caused by our behaviour, so without further ado I reveal to you the carbon footprint of the Davidson household in 2019, calculated with the carbon calculator; the lessons I have learned, follow.

Lessons learned:

- Don’t have an overseas wedding (CO2 from our wedding was around half of our emissions for the entire year, and more than 80% of this relates to the flights of guests)

- If you must get married overseas, make sure you only do it once

- Live closer to your in laws (admittedly, this may generate non-carbon-related externalities)

- Avoid flying, if possible

- If you do, don’t fly business class (it emits nearly three times as much as economy class)

- Ferries emit just about as much as planes

- Try not to drive as much, and if you must, check the emission standards of the car

- Cut down on taxi, bus rides and replace with walking, tube or train, where possible

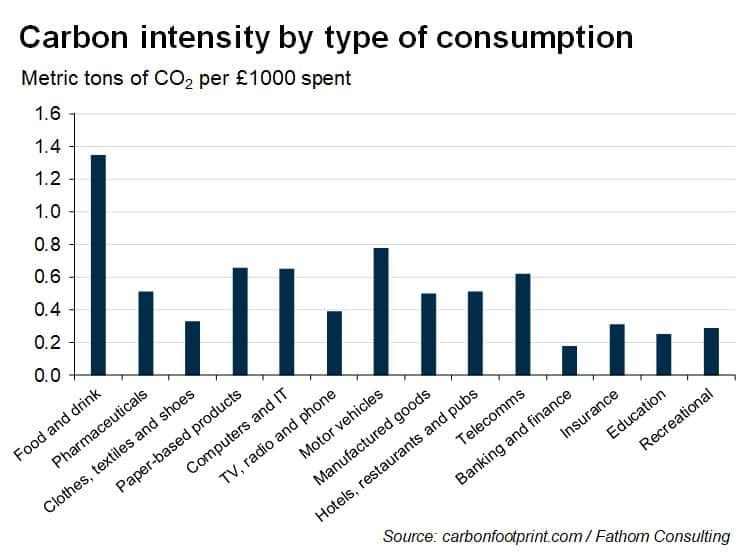

- The most carbon intensive (per £ spent) thing we consume is food and drink (particularly meat eaters) followed by motor vehicles, paper-based products and IT equipment

- The least carbon intensive thing we consume is banking and finance

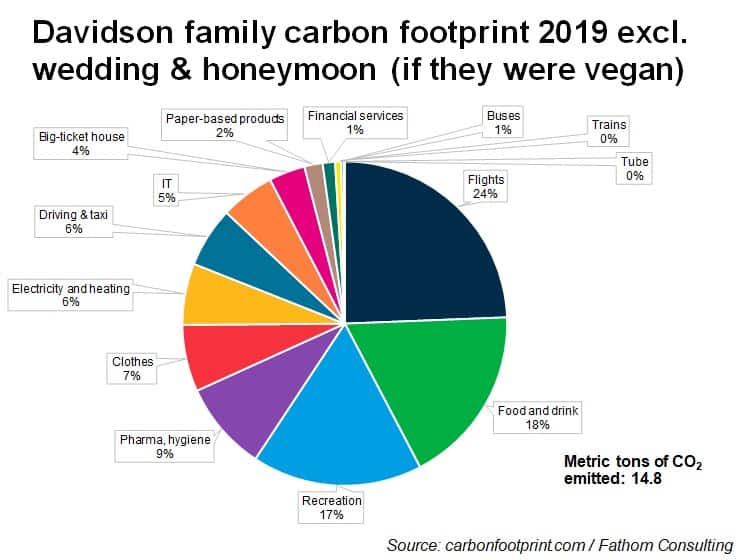

- Eat less meat

- Waste less food

- Tsking when you get a plastic straw is not enough to save the planet (fine to keep doing it though)

- Leaving the bedroom lamp on isn’t such a big deal (although no point in doing it)

After calculating your carbon footprint, my main top tip would be to consume less and spend your money on things that don’t pollute that much. And if you must consume and fly, or have weddings overseas, like me, you can always donate money or invest in projects, like planting trees, that will offset these emissions. To try and offset the CO2 emissions generated by my overseas wedding and extravagant honeymoon, I’ve given £330 to an organisation that will plant trees in Kenya which will hopefully suck up as much carbon as that generated by the wedding and honeymoon.

At the end of the day, life is not all about economics, and not everything can be explained by constrained optimisation theory; even if it could, human utility is complex and is not consistent across people and it isn’t necessarily maximised by consuming more. A philosopher might say that happiness comes from having limited wants. This might be particularly prescient when considering the environment. A normal person might feel that the truth lies somewhere in between. Worth a thought.

[1] And it turns out that ferries emit just about as much carbon as planes, so I ruled out the ferry option. Buses are not the cleanest mode of transport either so given the lack of connectivity between the two cities with rail, not only was the trip long and expensive, it wasn’t entirely clean either. Trains are the way to go, but the connectivity between London and Klaipeda is lacking.