A sideways look at economics

If, like me, you follow coverage of the war in Ukraine closely but aren’t an expert on Sino-Russian relations or a historian, you probably think Russia and China are best friends. After all, the bromance between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping has ‘no limits’, or so we are led to believe. I’ve grown to accept this narrative, although with a nagging feeling at the back of my mind that this isn’t as accurate a description as the narrative intends. So, when I saw a book called The Amur River, Between Russia and China, I thought I should give it a read to find out more. I bought it, read it and will share my thoughts about it with you today.

A good travel story either tells you about a place you don’t know much about or a journey that not very many people have travelled. This book does both. The British author Colin Thubron, who speaks Russian and some Mandarin, does a nice job of describing the history of this complex region as he meets a cast of interesting characters along his journey. He is 84 years old, and began this journey and started writing this book only a few years ago. Sharp intellectually, impressive physically, as highlighted by him travelling for weeks with a cracked rib and sprained ankle, before fishing, drinking and talking politics with burly Russians in remote Siberia.

I’ve always loved travel and feel that it is the best way to learn about life. I’ve done a few epic(ish) trips so far – travelling through South America, parts of Africa and the Middle East – which has given me a strong reference point for a lot of how I see the world today. Nowadays, I get most of my news and information about the world from behind a desk in London. So, even though I consider myself open-minded, my worldview now is bound to be biased and imbalanced. A fresh perspective is needed.

Thubron’s story starts in the marshes of Mongolia and ends close to Sakhalin Island in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. The river separates Russia and China for hundreds of kilometres, before flowing north through Russia. Because more of the river flows through Russia than China, and because it flows into the sea in Russia, I think it is fair to say that the river has more significance for the former than the latter.

Back in the day, the Russians hoped that the Amur could be an economic artery for East Russia, a bit like the Mississippi for Central and Southern United States. But that never happened, partly because the river is so hard to navigate (sandbanks, currents, rocks, uneven depths and it freezes in winter) but also because Russia is so big, hard to manage and not very well run. The East of Russia is completely neglected (politically, culturally and economically) compared to the West and it will take a lot more than just a river to change that.

The history of the river is brutal, even by Russian standards. Cossacks travelled down it, settling on its banks, killing people and communities along their way. But then the Cossacks themselves were killed, when they fell out with the powers that be. The remoteness and brutal winters were killers too. Thousands of convicts, political prisoners and others have been transported along the river to work on mines and forced labour camps over the years. All of this on top of the generalised horrors of Stalin and the 1917 revolution. No wonder the people living there are ‘different’. [1]

This brutality wasn’t just a Russian thing. The Russians and Chinese have been at it for hundreds of years. The river and a lot of land north of it was Chinese for hundreds of years and ratified in the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk. But things didn’t stay that way: imperial Russia took this land in the mid-19th century. This was ratified in the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and then, for good measure, Russia took all the land East of the river to the Pacific Ocean too (see 1860 Treaty of Peking). China wasn’t and, still, isn’t very happy about this. It was around this same time that Britain took Hong Kong from China. Could China ask for this land back – as it did with Hong Kong? How would Russia react?

The scars run deep. Even in between these periods of conquest and reconquest, there have been skirmishes between the two sides – across the river, on the river, on contested islands and sandbanks in the middle of the river. There is a widespread Russian paranoia and mistrust of the Chinese: “They’re everywhere, the f***ers”, Thurbron was told more than once. They aren’t, actually. Plus, the Chinese that do don’t mingle very much with Russians, unlike people from other bordering countries like Kazakhstan. Perhaps this fuels the suspicion of the Russians, especially as Chinese commerce is now so prominent.

This sort of paranoia was one of the reasons that Russians massacred thousands of Chinese men, women and children near Blagoveshchensk in 1900. The museum in Blagoveschensk doesn’t say much about this. The museum in Heihe (a Chinese city on the opposite side of the river) does. Unsurprisingly, the Chinese, especially those in the border region, are resentful to this day. Not such great friends after all then. Admittedly things can change (the US and UK are friends even though they fought a bloody war centuries ago). But their relatively fresh and seemingly unsettled acrimony is perhaps why Russia and China weren’t friends for most of the 20th century, even though both, as communist nations, had common Western adversaries then.

It wasn’t quite so long ago that the Russian establishment wasn’t quite as gushing about the mutual friendship between the two countries. In 2000, Putin himself warned that if nothing was done within a few decades the Russian inhabitants of the East would be speaking Chinese. Other prominent commentators warned that Russia would be seizing Russian resources in the future. Some of the Russians Thubron met thought that China was doing exactly that. I’m not convinced about the seizing, but buying, illegally, with corrupt local officials turning a blind eye, seems likely. Another source of resentment among the people.

The difference between the discourse of politicians and the man on the street is striking. (This is not unique to this region, of course, although it is worth thinking about how and why these things are different and what the implications of this might be.) This sort of thing was nicely highlighted by Thubron – even though his book was about travel, not Sino-Russian relations. I wonder then, just how close Russia and China can grow, politically, without this becoming a problem with the populace. Will the political elite force this, even though the local populace don’t want it? Also, what will the people do if the politicians force it? Resign and accept most likely – until they don’t.

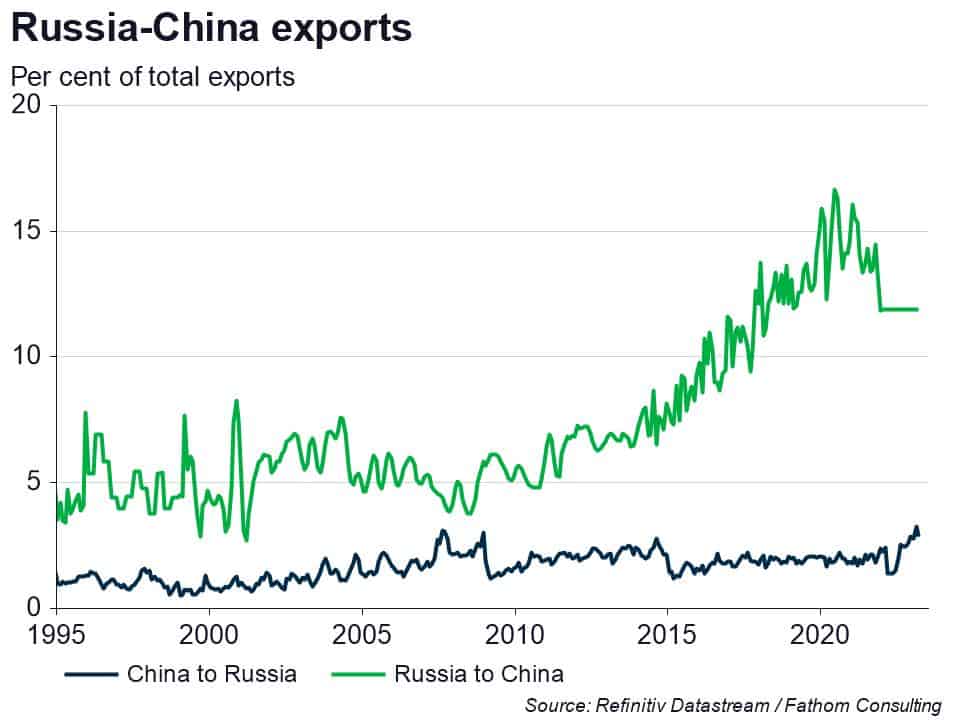

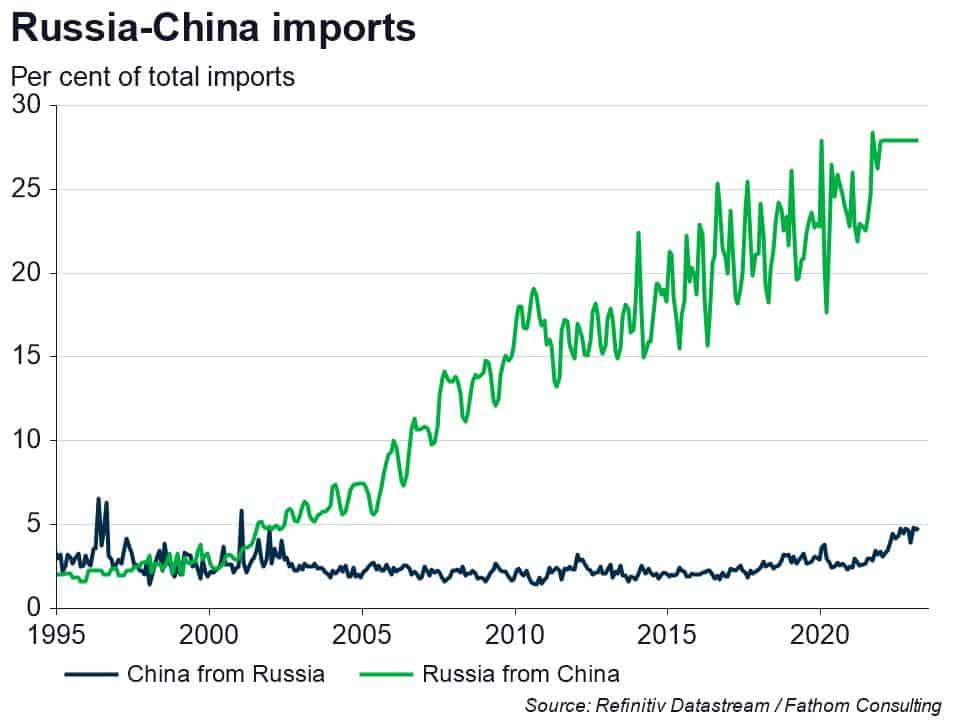

Russia and China may have a shared interest in hoping for a decline in Western hegemony and have a desire for a more multipolar world. But what happens when this marriage of convenience ends, for whatever reason? Or if political relations sour again? There is a huge imbalance here, in so many ways: two million Russians along the shared border versus 110 million Chinese; a growing Russian dependency on exports to China and imports from China; big disparities in economic performance; dependency on oil versus leadership on the energy transition.

One reason for the peace and equilibrium these past decades, I suspect, was superior Russian military strength. During his trip, Thubron found himself close to some major joint Chinese and Russian military exercises (which may explain why he was later temporarily detained on suspicion of being a spy). Thubron’s reflection was that this was perhaps not so much ‘cooperation’ as a ‘show of strength’ by Russia to China: don’t even think about it. But with China’s military and economy on the ascendancy versus Russia’s, this equilibrium and friendship might not be as stable as it seems. Happy Friday.

[1] After Thubron’s taxi got stuck in a ditch in the middle of nowhere, sometime later a farmer appeared with a tractor, towed them back to the road and left without saying a word. “That’s how things are done here. This is Siberia.” said the taxi driver. Very kind, with the lack of communication during this interaction legendary in my opinion.

More by this author