A sideways look at economics

I’d been looking forward to it so much — experiencing the hustle and bustle of London, as I took up my highly sought-after role with Fathom Consulting during my placement year from the University of Bath. Bright lights, big city, and all that! But COVID-19 has taken the sheen off my hopes and obliged me to work from my family living room in Belfast. No window-shopping on Regent Street for me this year, unfortunately. On the other hand, there are benefits to being at home: living rent-free, cuddling the family dog any time I feel like it, and my mum’s famously delicious cooking (she told me to say that, by the way). And now there’s yet another benefit lined up for me, and indeed for everyone else in Northern Ireland: free shopping vouchers to be spent in the new year, generously handed out by the Northern Ireland Executive — one more example of the unprecedented transfers which governments are making to their citizens to soften the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the Northern Ireland Executive announced its £300 million stimulus package on 23 November, the £95 million high-street voucher scheme was by far the most talked-about measure. Pre-paid cards worth £75-£100 are expected to be issued to eligible citizens early in 2021 to be spent in local shops, restaurants and hotels. Apart from helping to increase demand after Christmas, when most people cut back their spending, the aim of the scheme is to support local, independent retailers who have suffered greatly during the pandemic.

The US government adopted a similar approach earlier this year when it issued cheques to the value of $1,200 to every eligible adult as part of the 27 March CARES Act. Unlike Northern Ireland’s citizens, who must spend their vouchers on the high street, Americans were free to spend the money as they wished — in fact, they weren’t even obliged to spend it at all.

So what does economic theory say about how transfers like those seen in the US should impact the economy? If we were examining this problem before the great financial crisis of 2008, we would most likely have been looking at it through the lens of a Representative Agent New Keynesian (RANK) model. RANK models assume a single, rational, forward-looking, representative household which aims to maximise its lifetime utility, where utility refers to the enjoyment or satisfaction households gain from consuming a good or service. Solving the household’s constraint optimisation problem gives us an important aspect of the model — the Euler equation:

U'(ct) =βU'(ct+1)(1+r)

This equation implies that in order for households to achieve maximum utility, the satisfaction they gain from consuming one unit today must equal the satisfaction they would gain from saving today and consuming 1+r units in the future, once discounted by their degree of patience, β.

The Euler equation had strong implications for household consumption behaviour. Whilst households were believed to be highly sensitive to changes in interest rates, due to the dilemma they faced between current consumption and savings, they were also assumed to be unresponsive to transitory changes in income. This was because of the Permanent Income Hypothesis, which argued that since individuals care about their utility over their lifetime and not just in the present, they would want to smooth their consumption over time.

How would this work in practice? If you (like me) still demand that your parents buy you a chocolate advent calendar every Christmas, you may be familiar with the idea of consumption smoothing. The satisfaction we gain from consuming a small piece of chocolate every day in the lead up to Christmas is far greater than the satisfaction we would gain from consuming all 24 chocolates on 1 December and having nothing left for the remaining 23 days. Because of this consumption smoothing motive, households’ marginal propensity to consume (MPC) — the proportion they would spend on consumption if they were given additional income — was believed to be small. Therefore, according to the RANK model, the fiscal transfers seen in the US would have minimal effect on aggregate demand.

However, RANK models came in for criticism following the great financial crisis when it was observed that household saving rates had spiked even though interest rates had fallen to an all-time low — thus contradicting the Euler equation. Since then, Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian (HANK) models have become more useful in analysing the impact of macroeconomic shocks on household consumption behaviour. A two-asset version HANK model allows households to hold both a high-return illiquid asset and a low-return liquid asset.[1] This enables us to account for a more accurate wealth distribution by effectively creating three types of households — poor hand-to-mouth households which hold little to no financial wealth; wealthy hand-to-mouth households which store their financial wealth in illiquid assets (like a family home) but have little to no liquid wealth; and households which hold substantial amounts of both liquid and illiquid wealth.

Both types of hand-to-mouth households are likely to have a high MPC, since most of their income is spent on essential goods such as food, bills and rental or mortgage payments. For this group of households, smoothing consumption is not always possible. In contrast, households with surplus amounts of liquid wealth are more inclined to save any additional income and therefore, on average, have a lower MPC. By taking account of the heterogeneity in liquid wealth across the distribution of households, HANK models produce a more realistic distribution of MPCs which are higher, on average, than in RANK models. This suggests that hand-to-mouth households are more sensitive to transitory income shocks and less sensitive to interest rates than RANK models would suggest.

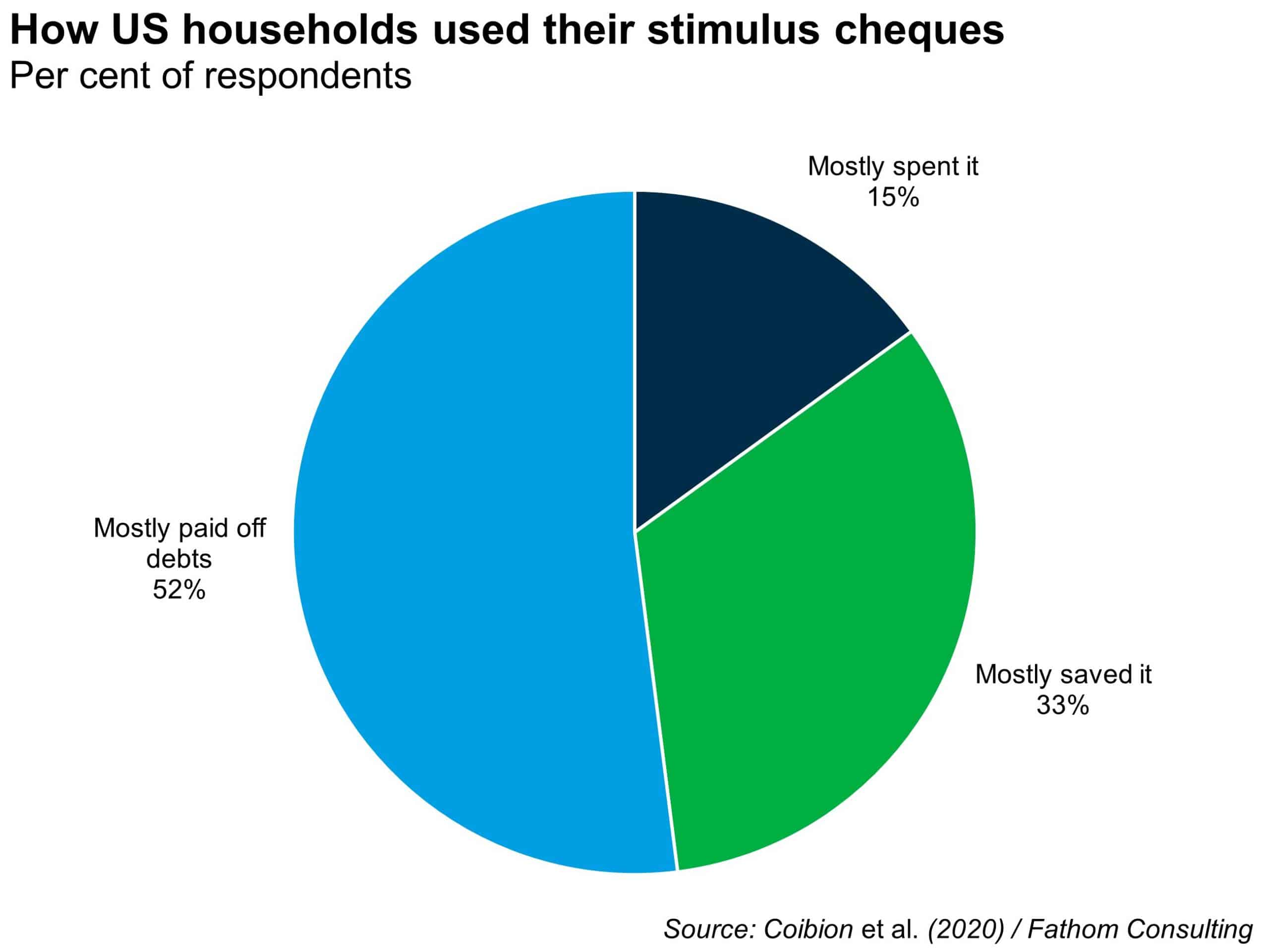

According to a recent survey of US households,[2] approximately 40% of the total value of stimulus cheques was spent, on average, whilst the remaining 60% was split almost evenly between savings and paying off debt. However, these results at the aggregate level mask the heterogeneity across individual household responses — 15% of households responded saying that they spent most of their cheque, whilst 33% saved most of it and 52% used the majority of it to pay off their debts. Furthermore, households which faced borrowing constraints spent, on average, 10% more of their cheque than unconstrained households, supporting the HANK model’s suggestion that poor hand-to-mouth households with little to no financial wealth have a higher MPC.

These results are consistent with the results from the 2008 US tax rebates, introduced in response to the great financial crisis[3]. Whilst handing out cash directly to citizens may improve individual well-being, it will not automatically lead to a multiplier effect within the economy since individuals are not obliged to spend the money. Does this mean that vouchers are always a superior policy option? Not necessarily. The NI high street voucher scheme will most likely result in MPCs of close to one, meaning that the entire value of the voucher is likely to be spent, since vouchers come with an expiry date and no option to save the money. However, if rich households use the voucher on items they were already planning to purchase, whilst saving the money they would’ve spent originally, this isn’t creating new spending within the economy.

HANK models allow policymakers to account for a more realistic distribution of wealth and heterogeneity in household MPCs, thereby allowing them to choose the most appropriate fiscal stimulus which will have the greatest impact on aggregate demand. And so, if governments want to ensure that policies create a large amount of new spending within the economy, policies should be targeted at the poorest households which have the highest MPC.

But the big question remains — how will I be spending my high street voucher? Soon after Big Ben’s New Year chimes have faded away in London, I had hoped to be out on Belfast’s Royal Avenue looking for ways to splash the cash. However, in light of the new lockdown measures which come into force in Northern Ireland on Boxing Day, it looks like I’ll have to wait a while. When lockdown is finally lifted, and the shopping crowds are again out in force, I’ll either join them with gusto or — just maybe — treat my Mum to a nice meal out as a thank you for letting me turn her living room into my very own Fathom office. Merry Christmas, everyone!

[1] Kaplan, G. and Violante, G.L. (2018). ‘Microeconomic Heterogeneity and Macroeconomic Shocks’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32 (3), pp. 167-94.

[2] Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y. and Weber, M. (2020). ‘How Did US Consumers Use Their Stimulus Payments?’, NBER Working Paper, No. 27693.

[3] Shapiro, M.D. and Slemrod, J. (2009). ‘Did the 2008 Tax Rebates Stimulate Spending?’, The American Economic Review, 99 (2), pp. 374-379.