A sideways look at economics

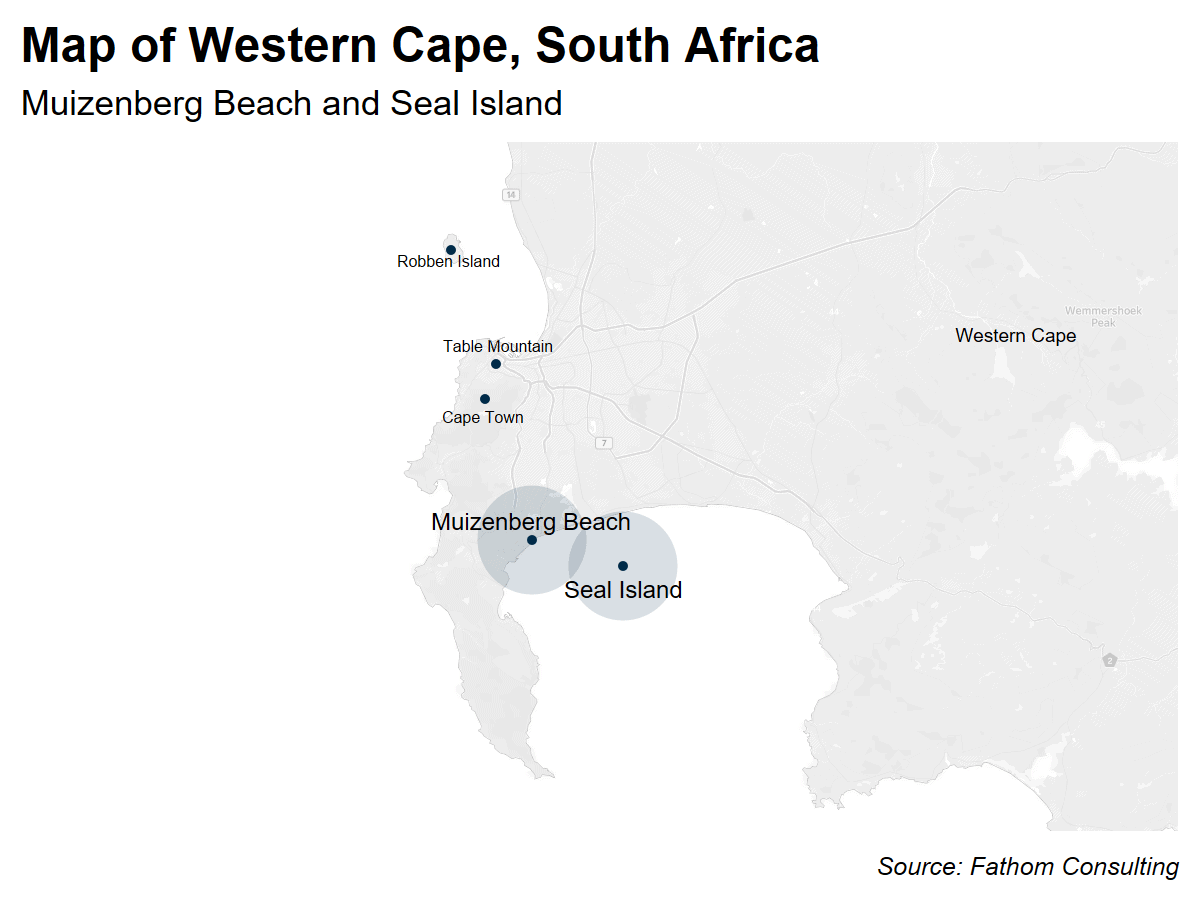

As a young boy growing up in Cape Town, I would spend hours bodyboarding with my friends, day after day, at Muizenberg beach. I always knew there were great white sharks around; after all, Seal Island — their favourite hunting ground — was only 10km away. Surfers have a code of not talking about sharks (spoiler: it is not clear whether I really am a surfer) but I was told that the sharks didn’t come close to the shore at Muizenberg and that the chance of being attacked by a shark was lower than being hit by a plane. So I carried on bodyboarding without a care in the world, occasionally keeping an eye out for planes. But now that I am older, more risk-averse and more questioning of statistics, I wonder whether I was right to be so blasé. Would I get in the water in Cape Town now? No. But is that rational?

The plane thing has been bugging me for years. In the context of the sea at Muizenberg, where no planes fly overhead, and a shark buffet is located a mere 20 minutes’ swim away for a great white, of course I would be at more risk of being attacked by a shark. (I was lied to, clearly.) The point I want to make in this TFIF is that statistics can be taken out of context and used to support a particular point of view. On sharks, there are generally two strong and diametrically opposed points of view. One is from people who have watched Jaws: it says that if you so much dip your toe in the water you are dead! The other, from those who haven’t watched Jaws: a plane hitting me on my bodyboard was more likely than me being eaten by a shark. Both are wrong.

There are many different types of sharks, and most of them are harmless to humans. And even the ones that can kill us, like great whites or tiger sharks, do not normally attack humans — they don’t like us (we are too bony) and attacks are normally a case of mistaken identity. It is also true that humans kill millions of sharks a year, while sharks kill about 10 humans a year, worldwide. Sharks should be more afraid of us. The probability of a shark attack is indeed very low. But that won’t help me in the water at Muizenberg beach.

As I write this, the probability that I will be attacked by a shark today is zero (although not if you watch any of the six films in the Sharknado franchise). As I sit at my desk in London of course I am more likely to be hit by a plane than attacked by a shark. If I go for a dip in the sea in England, it remains near zero, although not quite zero. But if I go for a swim in the ocean in South Africa, the chance of being attacked is still very low, but higher than it would be in England. And if I surf for two hours every day at Muizenberg, the chances are higher again. Context is everything, so statements like you are more likely to be hit by a plane are not helpful. That might be true if you swim in the ocean for five minutes a year on average. But obviously the more you are in the water, the more your chances of being attacked. And if more sharks are in the area, the probability is obviously higher.

As I researched this TFIF, I stumbled across a blogpost that described the point I am making and it did the dirty work of calculating the probability of getting attacked in three different, sharky, locations: Reunion Island, South Africa and Australia. The author noted how most shark attacks are on surfers or bodyboarders, and that the probabilities of attack should be compared to the number of active surfers. And in most places the share of the population that surf is only a tiny fraction of the overall population. For the average surfer in Reunion, he calculated that the probability of an unproved fatal shark attack was 12 times higher than the probability of dying in a car accident in France. This was nearly 60 times higher than the probability of a surfer suffering the same fate in South Africa. For hardcore surfers who spend more time in the water, the chances rise: in South Africa they have a 1 in 6000 chance of being attacked in any given year, which is low, but not staggeringly low, and higher than the chances of being involved in a fatal car crash.

In other words, the probabilities of me being eaten by a shark should not be compared to the probability of the average person being eaten by a shark. Just like the probability of me dying in a bungee jumping accident are not the same as someone who regularly bungee jumps (I have no plans to bungee jump, ever). The true probability of being eaten by a shark could be expressed mathematically like this:

P (ebs)= β1 (ocean)+ β2 (GW)+ β3 (SS)+ β4 (SF) + β5 (month)+ β6(time)+ β7 (WM)

Where:

- ebs = eaten by shark

- ocean = whether you are in a pool or the ocean

- GW = distance from great white shark breeding ground

- SS = shark spotters present

- SF = spear fishers with bloody fish nearby

- month = month of the year (in Cape Town, attacks are more likely in summer)

- time = time of day (attacks more likely at dawn or dusk when sharks hunt)

- WM = murkiness of water (attacks more likely in murky water due to mistaken identity)

Since I don’t have all the data, I cannot calculate the coefficients or work out the true probability. But the data from the blog, and the fact that there have been two shark attacks on surfers on Muizenberg Beach (neither fatal) since I stopped surfing there in 1999, seem more likely to be accurate than the perceptions of many, which range from the ridiculous to the improbable.

The key lesson in all of this is whether the actual probability is very different to your perceived probability. And if it is, and you know it, reassess your decisions. This is as true for shark attacks as it is for anything else in life. On reflection, it is probably fair to say that I was too blasé over bodyboarding when a child but am too scared about going in the water now. But it also makes me wonder whether it was a good idea to take a dip in the Okavango Delta when I had seen a crocodile in the water two days earlier. Our guides said it was, and sometimes you’ve got to go with your gut. Perhaps the topic for my next TFIF ought to be: the economic value of going with the flow, living with risk and uncertainty, compared to the stress and loss of fun by overthinking.

More by this author