A sideways look at economics

Ever feel like you’re doing all the work?

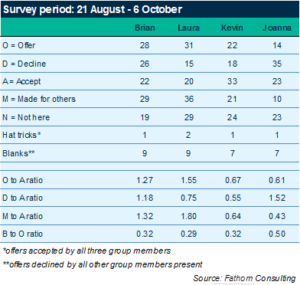

At Fathom we have an unwritten code of offering our colleagues a drink whenever we make one for ourselves. A legacy, possibly, of the early years of the company, when the team was a lot smaller. Or testament to what a nice, friendly bunch we are, perhaps. But for all of this niceness, there have been, and may still be, a few issues with this system.

When I joined Fathom, making a drink could turn into an ordeal. I could barely remember everybody’s name never mind how much milk, or how many sugars, they liked in their tea. The prospect of making up to 17 drinks ultimately changed my behaviour and presumably that of my colleagues, too. There were many ways to game the system: get to work before most people arrived and make your drinks then; pick up a latte on the way to work; wait for somebody else to offer you a drink even though you really want one now; offer to make a drink straight after somebody else has made a drink to give the appearance that you offer every now and then; make a scene every time when you offer a drink so people remember it, creating the impression that you offer more than you actually do; eat lunch at your desk, but pop out for a cheeky espresso afterwards; take the passive-aggressive approach – i.e. offer drinks in a really hurried voice in the hope that the person receiving the offer senses your anxiety, feels sorry for you and says no, or simply doesn’t have enough time to decide if they want a drink before you walk off.

Such a system was not ideal. After all, comparative advantage suggests that it was inefficient for senior Fathom employees, such as our CEO, to be making 17 drinks for the team. (When it was our CEO’s turn to make drinks, he would go out to the coffee shop and buy 17 coffees.) It’s not that senior Fathom employees aren’t skilled at making coffees (although I have some doubts), it’s just that senior employees are better off using their time, knowledge and experience on the stuff that other members of the team can’t do. For example, our CEO may be brilliant at everything, but since he has a comparative advantage at being a CEO, he’s better off focusing on that.

We use the theory of comparative advantage in our lives more than we probably realise. For example, we might decide whether we should do our own housework or whether we’re better off working a little harder, earning a little more money and paying somebody to do that task for us. Should I iron my own shirts, or does it make sense to send them to the laundry? They iron them better than I do, and in less than half the time. Surely it’s more efficient for society as a whole that I focus my energies on being an economist and pay for my ironing to be done. Many readers would probably agree with that, unless, of course, you enjoy a bit of extreme ironing, like these gentlemen.

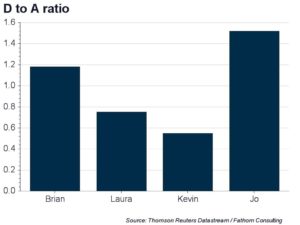

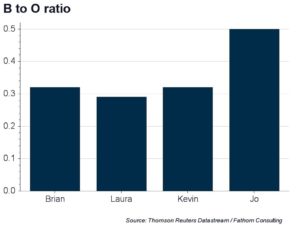

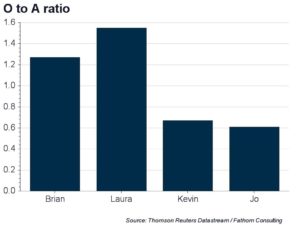

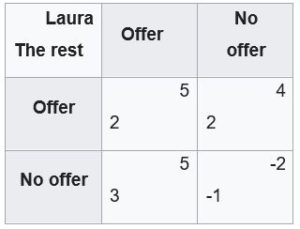

Admittedly, these were not the reactions I was expecting. I thought that Laura would demand that her colleagues shoulder more of the drinks-making burden, and that Kevin and Joanna would admit that they are rational agents and that the logical thing for them to do when they want a drink is to simply sit and wait for Laura to make one for them. After all, research has shown that among flatmates, the person who normally bears the burden of cleaning the flat is the person with the lowest tolerance for mess. It’s a similar situation to drinks making really. The one with the lowest tolerance for not having a drink is the one that makes all the drinks: that would be the one who drinks the most – i.e. Laura. A payoff matrix for the situation might look something like this:

In this world the dominant strategy for Laura is to offer to make drinks since she will get a better payoff by doing so. For the rest of us, we would only offer to make a drink if Laura didn’t offer. But we know that will never happen, at least when Laura is in the office, so we never offer to make drinks. The equilibrium outcome is Pareto-efficient and in the bottom left quadrant.

But what if Laura didn’t like making drinks so much? Such situations do not always lead to such optimal outcomes, and we are not all lucky enough to have a Laura sitting next to us. What if Laura didn’t like drinks any more than we did? A drink standoff could ensue. We may even feel guilty and decide to help Laura with the drinks from time to time – how might that change the payoff?