A sideways look at economics

I’m only happy when it rains

I’m only happy when it’s complicated

And though I know you can’t appreciate it

I’m only happy when it rains

You know I love it when the news is bad

And when it feels so good to feel so sad

I’m only happy when it rains

Garbage, Only Happy When It Rains

Fathom’s annual summer party is approaching. This is a function aimed at clients, friends and family. Our hope and expectation is that it will raise the stock of happiness among that group of people, and lift the general mood in a small way.

But the problem with parties, which is the frustrating thing for the host, is that they don’t always deliver the goods, in terms of making people feel happy. The impact on happiness depends critically on what attendees were expecting, and then on what their personal preferences are relative to those expectations.

Some arrive armed with the colourful invitation and a hope that this will be the party to end all parties, more fun than they’ve ever had. When the party turns out to be good, but not necessarily up to those unrealistic expectations, those optimists will leave feeling bitterly disappointed.

Others (and this author knows several people who would fit into this characterisation) are always plagued by a certainty that someone, somewhere, is enjoying an even better party, no matter how good the party they are attending, and that feeling undermines any enjoyment they can extract, so they again leave feeling disappointed. Sometimes, therefore, even though many attendees may have enjoyed themselves as they expected to, the stock of human happiness falls slightly.

Finally, there are those among us who, like the author of the lyrics quoted above, take pleasure in things being bad – feeling somehow validated and justified in their appetite for complaining no matter what.

In sum, what we hope the party will deliver is not always the same as what the party will deliver.

Why, I hear you cry, is any of this relevant? Apart from reflecting the usual anxieties of anyone arranging parties, parsed through the fevered brain of an economist, there is a topical, global story here too.

The World Happiness Report, recently released, compares average happiness levels across 155 economies. It is a fascinating read. It also describes some detailed econometric work assessing the marginal impact of a range of different factors upon happiness across the pool of countries in the data set. Those factors include: real GDP per capita; the level of social support; life expectancy at birth; the degree of personal freedom; the level of generosity; and perceptions of corruption. Incidentally, the average self-reported level of happiness at Fathom Consulting is higher than the western European average, though we cannot reject the hypothesis that Fathom staff are (in this respect) a random draw from that underlying population.

Welfare economics is all about trying to design ways of increasing human happiness (however defined) by manipulating the various levers of economic policy. But a number of issues present themselves – too many for them all to be treated here. Let’s focus on one: the role of per capita GDP in influencing happiness. The belief that this relationship works has been the foundation of macroeconomic policy since the start of the industrial revolution at least.

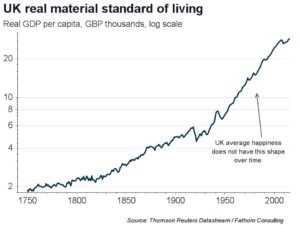

This issue resonates with the party analogy above. Surely, if we can make the average person better off, then the sum of human happiness will increase? (Just as, if we spend more on the venue, the food, etc., we hope to make attendees at the party happier.) That is indeed what the World Happiness Report concludes. However, reflect on this: there is no evidence that human happiness on average increases over a long period of time. And, by definition, human happiness as measured in the World Happiness Report is bounded between 0 and 10. But GDP per capita is trended upwards. How can a trended variable like GDP per capita (albeit in log form) have a consistent impact on an un-trended variable, happiness?

In the long run, the level of GDP per capita cannot determine human happiness. It must be something else, for which GDP per capita is a proxy.

If our party analogy is pertinent, then perhaps it is GDP per capita relative to expected GDP per capita that matters? Or, more precisely, the distribution of real income per head across all individuals relative to their expectations of what their real income ought to be. If those expectations are slow-moving, and average GDP per head increases relative to those expectations, that will tend to boost average happiness, while if it falls relative to those expectations, average happiness will fall. That would account for the sign and the significance of the coefficient on GDP per capita in the model of happiness: it only matters if GDP per capita is surprisingly high or low. On average, it will be neither.

Alternatively, it could be GDP per capita relative to perceptions of other people’s GDP per capita that matters: not our absolute standard of living, but our relative standard of living. Again, there are resonances with the party problem – it is hard to please those who are obsessed by what might be happening at other parties. If it is our relative standard of living that matters, then by definition this cannot increase on average over time, but a big increase in average GDP per capita in country (i) will often be consistent with an increase in the relative position of that country too, compared to other countries. Again, this would account for the sign and the significance of the coefficient on GDP per capita in the model described in the World Happiness Report.

One thing we can rule out is the ‘Garbage’ mentality as being a dominant theme in determining happiness. If the perennial complainers among us, who prefer bad outcomes to good, were in the majority, then the sign of GDP per capita would be different in the model. It sometimes seems, particularly in the UK, as if complaining about everything is as ubiquitous as the rain, but the evidence globally points in the opposite direction.

For those planning to attend our party who do subscribe to the ‘Garbage’ view of the world, rest assured: it’s summer in London, and the party is on a roof terrace. The chances of rain are high.