A sideways look at economics

What’s the most wonderful time of the year? Christmas? Quite possibly. But, ask a football fan and they may well tell you that it’s right now.

As March rolls into April and arctic chills are replaced by glowing sunshine (or so we hope), the football season also begins to heat up, with the fixture list soon dominated by season-defining clashes. And I’m not talking about that fancy continental competition with a somewhat ironic title.[1] Rather I’m referring to what those on the terraces call ‘proppa football’ – that is, the Football League.

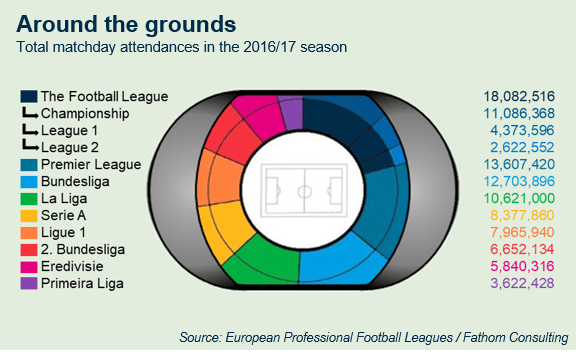

For the 72 clubs outside the Premier League there’s an awful lot to play for. Some are challenging for promotion, others fighting off relegation. Granted, it may be less glamorous than top-flight football and is a less common topic of ‘office banter’, but nevertheless the interest is clearly there. Indeed, more people attended Football League games than Premier League matches last season.

But, the Premier League remains ‘The Dream’ for many fans, and players relish the opportunity to compete against the very best (and Arsenal). And rightly so, it’s where the money is! Which brings us on to a topic of heated debate – why are footballers paid so much? More specifically, do higher wages increase the chances of success?

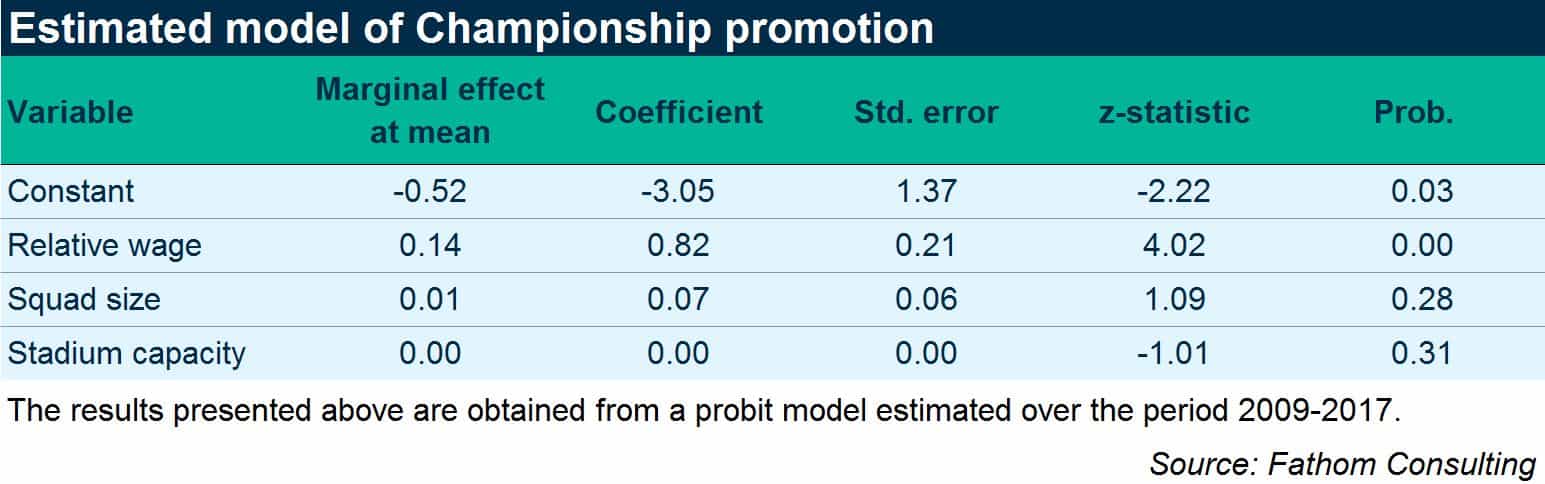

To test this, we put together a simple model, where the likelihood of promotion from the Championship is modelled as a function of average salaries, squad size and a measure of club stature. The results show a strong correlation between player salaries and promotion prospects. Indeed, the results indicate that this is the strongest single predictor of club success, and suggest that a club paying wages double the league’s average would have a 14% higher likelihood of promotion.

However, drawing conclusions from this model may be more complex than it appears at first blush. Indeed, the econometric results don’t explain the apparent relationship between higher wages and the likelihood of success, just that it exists. Economists might offer several competing explanations for these findings:

Higher wages enable clubs to attract better quality (more productive) players and this increases the likelihood of success on the pitch. That clubs attempt to take advantage of this channel is beyond doubt. Sometimes it works – for example Sergio Aguero’s transfer to Manchester City – while other times it does not –

Fernando Torres, Andriy Shevchenko and Michy Batshuayi to Chelsea (anyone to Chelsea really).

Raising the wages of the current squad could increase their productivity. Economists supporting this train of thought might reasonably argue that higher wages would induce players to exert greater effort through increasing the expected cost of dismissal – as predicted by ‘efficiency wage models’.[2] Such a channel may plausibly be expected to work in the Football League given that unemployment is a) costly, which it is given the salaries they would lose and b) a likely prospect, which is also true when one recalls that footballers are typically employed on short-term contracts and are thus easy to release at the end of the season.[3]

Higher wages are a sign of a successful club, not the cause of one. Such an argument is put forward by Szymanski and Smith,[4] who argue that past triumphs endow successful, more established clubs with additional revenue (for example through higher TV receipts and prize money). This affords them the luxury of better training facilities, larger scouting networks and access to top-quality players. Consequently, higher salaries could reflect the fact that clubs are already successful. Even if the prior two channels are operative, this third channel could act as barrier to smaller clubs attempting to spend their way up the footballing ladder.

The empirical work in our sporting example has not allowed us to distinguish which of the three transmission mechanisms is more dominant. Football club chairmen face a difficult conundrum, one which is well understood by CEOs in all industries. Interviewees will often highlight the first channel as justification for their salary demands while employees may stress either of the latter two. Either way, the message to CEOs is the same – spend more money! Their task, however, is to distinguish which route provides the most bang for their buck.

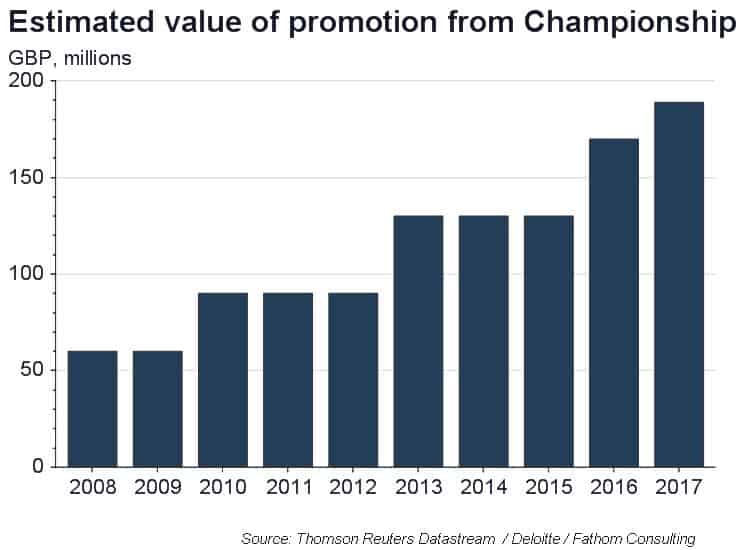

Even if one could decipher which of the channels is more potent, it doesn’t necessarily imply that footballers are paid the correct wage. When deciding player salaries, a football club chairman must weigh the known costs – in terms of higher wages – against the expected benefits (which depends upon the likelihood of promotion and the potential revenue that top-flight football provides). Assessing whether the expected benefits outweigh the costs would be a substantial piece of work in itself and is beyond the scope of this week’s TFiF. An even more complex task is to assess the actions of club owners who often make apparently irrational decisions, even when the pecuniary costs exceed the expected benefits.

However, what this TFiF has demonstrated is that higher wages are associated with a greater chance of promotion. For fans dreaming of success, the message seems clear; for chairmen who have to decide how best to spend their money, there’s still a lot to consider.

________________________________________

[1] Champions League – seriously? When did Liverpool last win something?

[2] See Carl Shapiro and Joseph E. Stiglitz, ‘Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Discipline Device’, The American Economic Review, 74/3 (1984), pp.433-444. The authors’ model offers employees the binary choice to either ‘work’ or ‘shirk’, with the latter option assumed to imply zero productivity – a more severe assumption than the example described in the text. In their basic formulation, workers will only exert effort if a no-shirking constraint – which implies that the benefits of effort are greater than the expected cost of shirking – is satisfied.

[3] While the existence of the efficiency wage channel seems plausible within the lower leagues, it is perhaps less effective at the very top of the footballing pyramid, given the enormous sums that some players earn. Consider, for example, the case of Carlos Tevez, who reportedly earned £1 every second during his recent stint at Shanghai Shenhua. But to someone like Mr Tevez, who presumably has millions already in the bank, what’s a little more really worth? The answer is probably not that much. It probably won’t buy him anything that he can’t already afford. So, that begs the question of why he should bother at all. Indeed, the work of Mssrs Stiglitz and Shapiro would give this precise result if the cost of effort exceeds the marginal benefit of work. Shocking, right? Next thing you know footballers might even take mid-season holidays to South America. Oh wait…

[4] Stefan Szymanski and Ron Smith, ‘The English Football Industry: profit, performance and industrial structure’, International Review of Applied Economics, 11/1 (1997), pp.135-153.