A sideways look at economics

There are nine million bicycles in Beijing.

That’s a fact,

It’s a thing we can’t deny

Katie Melua, 2005

Let’s be clear, there are not nine million bicycles in London. That would imply almost one bike for every person in London. But there are a lot. What’s more, spurred on by Britain’s quartet of Grand Tour winners (Wiggins, Froome, Thomas and Yates) and Britons’ growing desire to keep fit, bike usage seems to be on the up. Indeed, a quarter of Fathom’s staff now commute on two wheels and, with two more planning to participate in long-distance rides this summer, the company’s lycra-clad peloton continues to grow.

But bike ownership is no longer the only game in town ― nowadays rental proves just as attractive an alternative. Indeed, on yesterday’s walk to work I spotted eight Lime Bikes parked in Finsbury Square for the first time. The latest addition to London’s blossoming technicolour bike-hire market follows in the steps (or rather pedals) of the bumblebee-yellow Ofos and the tangerine-orange Mobikes.

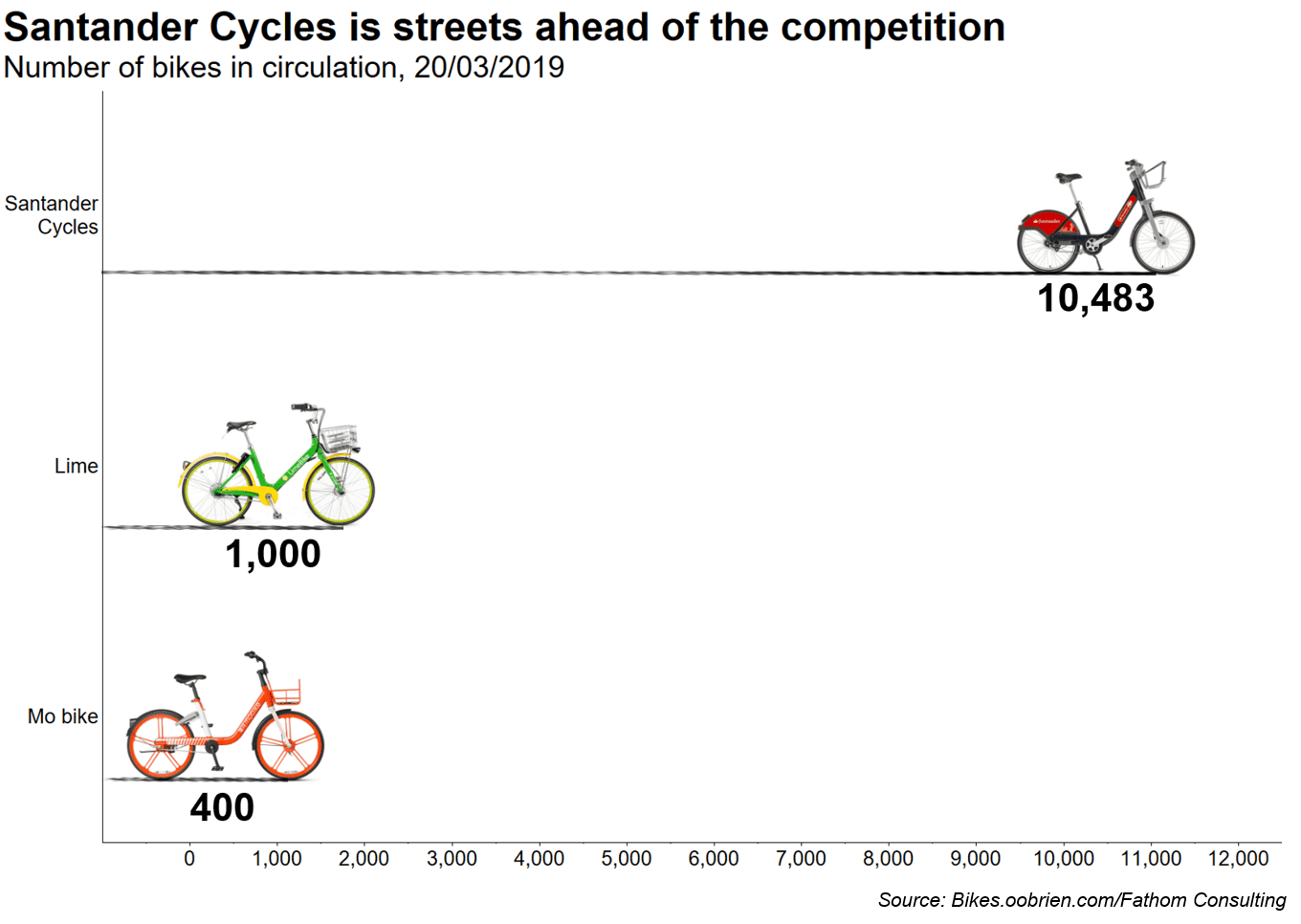

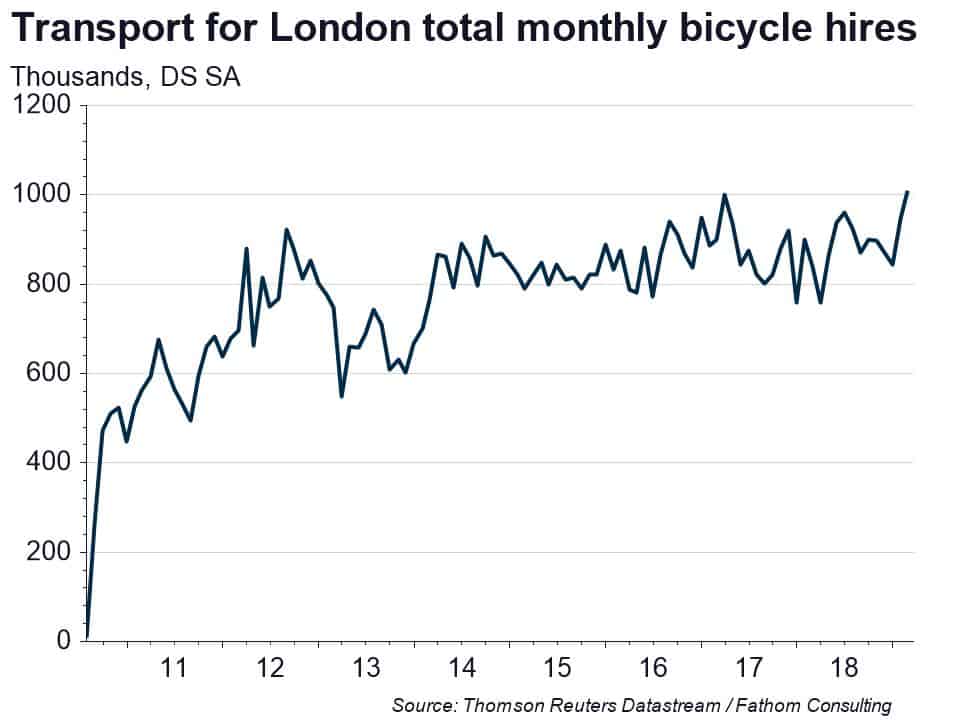

However, all of these are dwarfed in scale by Transport for London’s (TfL) Santander Cycle Scheme which claims to have more than 10,000 bikes across 750 sites. Indeed, data show that these bikes (still dubbed ‘Boris Bikes’ after the city’s former mayor rather than ‘Sadiq Cycles’ after the incumbent) made almost 29,000 journeys per day last year.

But, can the new upstarts challenge the dominance of the TfL-backed scheme? At first blush, an economist would probably rebuke such a suggestion, claiming that the incumbent should benefit from network effects. These effects occur when increased usage of a good (or service) increases the value of that good to all other individuals. An oft-cited example of this is the telephone. In the early days of the phone, few individuals owned one and consequently there were few people to call. However, as ownership increased, the more phones there were to call and the more valuable the phone became.

The same logic should follow in the market for bike hiring ― as usage increases, more bikes will be supplied, more docking stations will be created, people will find it easier to deposit bikes near their destinations, and then more people will be willing to hire. As a result, the bike company with the largest number of docking stations ought to become the most widely used. However, the advent of dockless bikes may have overcome this ― indeed, evidence from China, Cao et al. (2018)[1], shows that the expansion of Mobike into regions where Ofo was operating encouraged increased usage of both providers, suggesting that the removal of post-ride docking concerns means that people now simply use whichever bike is nearest.

So, who’s likely to come out on top of this Great British Bike Off[2] competition and can any of the new upstarts end the Boris Bike’s hegemony? In the short term, the answer is probably no. Boris Bikes continue to receive support from the local government and the scheme is able sustain the higher costs involved with operating a wider service. Rival Ofo has already backed down and effectively withdrawn from the capital, while Mobike’s struggles in Manchester suggest that it’s unlikely to match TfL’s scheme. That being said, new competitors continue to enter the market.[3] At best, more competition causes increased usage through network effects (and may introduce more competitive pricing) while at worst there’s no change in the current (upward) trend in bike hires. Either way, cycling continues to be the winner.

[1] Guangyu Cao, Ginger Zhe Jin, Xi Weng and Li-An Zhou, ‘Market Expanding or Market Stealing? Competition with Network Effects in Bike-Sharing’, NBER Working Paper No. 24938 (2018).

[2] Not to be confused with Graham Hoskins and Tom Woodrow’s motorbike series or the BBC’s Channel 4’s baking show.

[3] For instance, Cycle.land is reportedly planning to expand operations to London.