A sideways look at economics

Visiting family last weekend, I found myself having to answer a question that I’ve heard on a regular basis since my engagement a little over two years ago, and which has become even more pressing in the eyes of my mother-in-law since the wedding last month: do I intend to change my surname?

The answer is “no”. I’m not entirely sure why, and I’m even less sure how to explain that to my mother-in-law.

Perhaps I’ve over-binged on the television adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. In this patriarchal world, the female lead is referred to and known only by the name ‘Offred’, a reflection that she is the possession of Fred Waterford, her master.

Although the world we live in is a far cry from that conjured up by Margaret Atwood, the expectation that a female should take the name of the ‘man of the house’ still seems to be prevalent, as evidenced by the abundance of well-wishers addressing cards to who they presume to be the new ‘Mr and Mrs S. Attard’.

This tradition of assuming the husband’s name originates from an abolished, and far-from-rosy, legal principle known as coverture. This stipulated that upon marriage “the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended”. In other words, she ceased to exist! In keeping with this, the husband took ownership of any assets that the woman held, while the woman lost her right to own property, sign legal documents, enter into a contract, or even keep a salary for herself.

Despite its unsavoury origin, I was surprised to discover that the vast majority of women still change their surname. A 2016 YouGov poll found that only 14% of women planned to retain their maiden name after marriage, a lower percentage than other studies suggest was the case in the 1980s — a time when doing so may have carried stronger connotations with equality and the abolition of coverture.

So, what motivates the small minority of brides that buck the name-change convention today, and can my findings help appease my mother-in-law?

Surprisingly, my less-than-scrupulous research method, which involved asking friends about the recently married women they know, produced a similar result to that of the YouGov poll, with 16% opting to keep their maiden name after the confetti had settled. Just under 5% opted to double-barrel, while the remaining 79% took their husband’s surname.

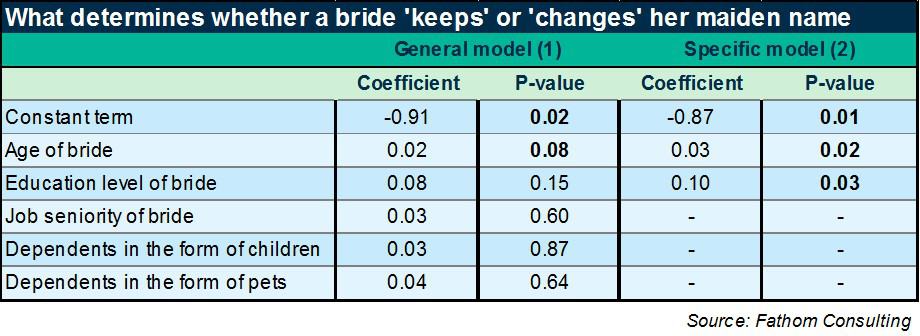

Using the additional information that my friends provided — age, education, job, and dependents (both pets and children) at the time of marriage — it’s possible to test which of these characteristics most influence a bride’s decision to ‘keep’ her maiden name. The regression results are displayed below, with bold text highlighting those of statistical significance at the 5% level.

The most important factor, it would seem, is the educational attainment of the bride, followed by her age. Both have positive coefficients, indicating that older and wiser brides are more likely to break with tradition than those on the nicer side of thirty. A consequence, perhaps, of having become more attached to their maiden name for professional or personal reasons over the years.

Put simply, they may have “made a name for themselves”!

In doing so, their name has become an intangible asset, it has ‘reputational’ value. And although hard to quantify, in their field their name may carry more weight than the groom’s does, perhaps explaining their decision. Equally, for others, changing names could provide an opportunity to trade up, benefiting from the ‘reputational’ effect of their husband’s name in a world of imperfect information.

And although job seniority is statistically insignificant in my sample, research suggests that more comprehensive measures of socio-economic status are positively signed and meaningful. Even within my sample, it was the likes of vets, doctors and lawyers (those least likely to be on first-name terms with their clients and deemed to be within the ‘professional class’) that kept their own surname. Teachers were the notable exception to that rule — the apparent difference being their socio-economic status! Another study based on US data from 2001 found that brides with an occupation in the arts — writer, editor, artist, actor etc. — were also more likely to keep their maiden name. The odds were even higher if the groom had a Ph.D, or the father-in-law was in the arts or academia. Grooms with patrimonial suffixes (Snr, Jnr) had the opposite effect.

According to my analysis, neither pets nor children were statistically significant, although I suspect (for the latter at least) this was a sampling issue.[1] There are bound to be other influences that my (admittedly simple) model fails to capture too, such as religion, family expectations and peer effects. It also ignores those that subsequently change their name after having kids. Indeed, plugging in both the mean age of brides in the UK[2] and the average educational attainment of a women at that age suggests that about 33% opt to retain their maiden name after marriage — a lofty estimate!

But one thing is certain, these findings are unlikely to reassure my mother-in-law, whose youngest is likely to drag his heels just as long as his elder brother, day-by-day reducing the odds of a conventional bride!

[1] Due to my data collection technique, I was unable to ascertain whether the children had the bride’s pre-marital surname or the groom’s surname, and therefore the likely direction of influence.

[2] Which is 35.1 according to the ONS.