A sideways look at economics

Lockdowns have not been good for the waistline of people stuck at home – not least me. Noticing that I was out of breath doing up my shoelaces, I dusted off the bathroom scales and… Horrors! An unpleasantly large number met my eyes. I had put on a corona-stone, and maybe more. A diet was required, but how much should I lose? The NHS weight loss calculator divided my weight in kg by my height in metres squared and gave me a BMI of 40.3. “You are obese,” declared the app, rudely. With mounting incredulity, I read that my “healthy” weight range was 48kg to 64kg. Are you kidding? I haven’t been 48kg since I had anorexia 40 years ago. That advice was not merely bad but dangerous. What kind of health metric was this Body Mass Index, anyway?

As it turns out, BMI was not originally a health metric at all, but as a measure of average size. It was Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer and statistician, who came up with the formula in 1832. Quetelet was not a doctor, and had no views on what weight was healthy. His quest to define “l’homme moyen”, or average man, by measuring different aspects of humanity (he personally measured the chests of more than 5,000 Scottish soldiers) and observing their distribution on a Gaussian error curve, made him the father of modern population studies. Quetelet’s obsession with measurements and dubious theories about how these connected to behaviour are also credited with inspiring the pseudo-sciences of phrenology and, even more controversially, eugenics. But that’s another story.[1]

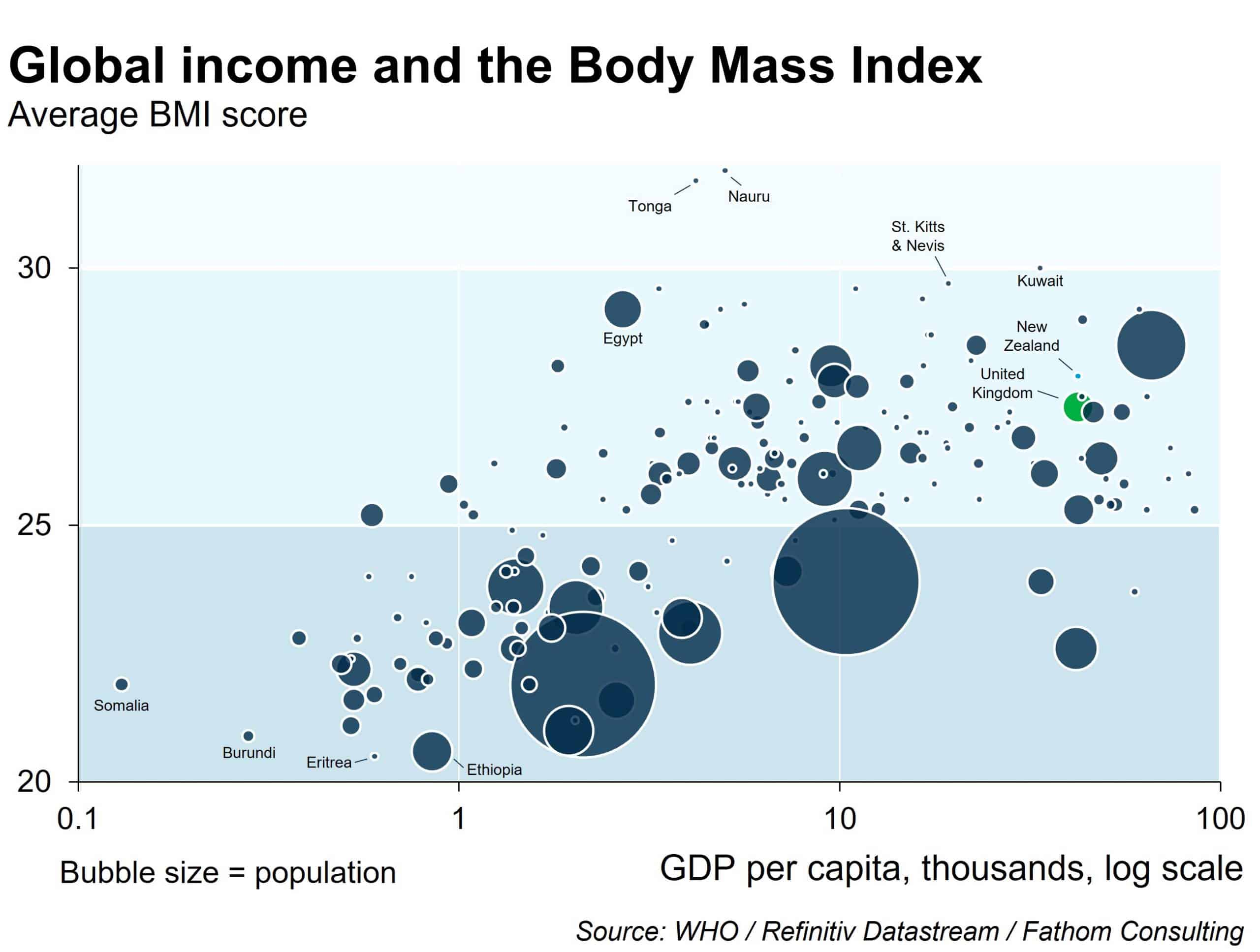

Quetelet’s index was picked up first by life insurance actuaries, enabling them to bump up the premiums of people with scores outside the “normal” range, of 18 to 24.9. The term BMI was coined in 1972 by Ancel Keys, who was researching different ways to measure body fat. Keys himself acknowledged that BMI was only 50% accurate in diagnosing obesity and called it the best of a poor bunch of diagnostics. Nonethless, the metric became part of the toolkit of every doctor and these days is used in a huge range of situations. As a way of comparing different nationalities BMI does have some use, and rankings based on World Health Organisation (WHO) population data make interesting reading. Obesity, it emerges, is not a disease particular to rich peoples or the decadent West. Britain, where the government likes to blame obesity for the nation’s official toll of 128,000 COVID deaths, comes about a quarter of the way down – significantly closer to the “healthy” range than New Zealand, a country which has experienced exactly 26 COVID deaths. The rankings suggest that genetic heritage has a strong influence on probable BMI, with economic, social, cultural and environmental factors also in play.

So far, so interesting, but these population-level BMI averages are merely a starting point. It is only through drilling down in the country-level data, broken down by age, gender and socio-economic group, that you start to see meaningful patterns emerge, like the childhood obesity crisis in Saudi Arabia. On their own, the flagship BMI figures are practically useless. And as with the macro data, so with the individual. The BMI range that so surprised me should only ever be a starting point: a trigger for your doctor to examine many other factors in order to see a meaningful pattern emerge.

Because what idiot would insist that everyone should weigh roughly the same? If you look at a college graduation photo, you will see an enormous diversity in height, weight and build. A single metric that claims to define what is “healthy” or “normal” for all nationalities, age groups and genders is simply nonsensical. BMI does not take into account that muscle is heavier than fat: Arnold Schwarzenegger at his physical peak was “obese”, if you believe the BMI range. It does not reckon with the fact that muscle declines with age, and elderly people with the same “healthy” BMI they had in their youth will be carrying more body fat; or that for South East Asian people a “healthy” BMI as low as 23 can be a precursor to diabetes. It fails to acknowledge that women and men have different body composition (the metric was based on male bodies). The NHS app tacitly acknowledges that BMI is fairly useless, offering a small link below its BMI calculator leading to a page where the many exceptions are listed.[2]

Unfortunately, the idiots who insist we should all weigh roughly the same are our doctors, who use BMI as a blunt weapon. As a writer I can assure you that the language we use matters very much, and medicine uses and normalises fat-hating language. Doctors would blench at telling a patient: “You are morbidly cancerous”, yet continue to interpret BMI with the use of the clinical term “morbidly obese”. It’s the only medical condition whose name includes the word “morbid”, a term with connotations of degeneration and death.

Language like this reflects society’s instinctive revulsion at fat people. In a classic US study in the 1950s, 10 and 11-year-olds were shown six images – a “normal” weight child, an “obese” child, one in a wheelchair, one with crutches and a leg brace, one with a missing hand and one with a disfigured face – and asked to rank which one they liked best. No matter where or how often the test was carried out, the child with obesity always came last.

If you think that attitudes towards fat people must have changed since the 1950s, they have – for the worse. Researchers at Harvard measured implicit and explicit bias among thousands of nurses, doctors, medical students and dieticians, and found that more than 75% had a correlation in excess of 1.0 with anti-fat attitudes. Male doctors in particular were more anti-fat (for example, endorsing statements like “Fat people are worthless”) than the general population.[3] Such bias routinely results in a lower quality of care. Doctors spend less time with patients they regard as overweight and are less likely to make eye contact. They are less likely to engage with the symptoms a fat patient describes, and three times as likely to fail to offer appropriate care, often deflecting queries about treatment by recommending that the patient should “eat less and take more exercise”.[4] The continued use of BMI encourages such mistreatment.

A report this month by the Women and Equalities select committee of the House of Commons sounded the alarm at the way BMI is also used as a rationing tool for care. A BMI in excess of 30 – the point where the label “overweight” becomes “obese” – is enough to bar patients from access to fertility treatment, and is a red light for some surgeries. The bias works to the detriment of patients with “healthy” BMIs too. Patients with eating disorders are routinely denied treatment unless their BMI is dangerously low. The use of BMI as a rationing tool has crept out into other areas of society: prospective parents can be banned from adopting children on the basis of their BMI. The select committee recommended an immediate ban on the use of BMI as measure to determine “healthy” weight, on the grounds that it was fuelling ill-health and poor care.

COVID has encouraged fat-blaming. Boris Johnson fanned the flames, with his confession: “The reason I had such a nasty experience with [COVID] is that although I was superficially in the pink of health when I caught it, I had a very common underlying condition. My friends, I was too fat.”[5] TV stations and newspapers fostered an erroneous impression of COVID wards filled exclusively with obese people, fuelling public anger and disgust. I quote at random from one fat-shamer on social media: “I’m tired of apologising for calling out the disgusting greed, laziness and weak will of fat people.”

Obesity is a complex disease whose origins can lie in genetics[6], hormonal changes, physical health, mental health, relative disability, culture, behaviour, parental modelling and environment – even, scientists are now starting to discover, in the gut microbiome, which differs significantly between thin and fat people. I put on weight after I tore my knee cartilage. Suffering from obesity is not a sign of weak will or greed or laziness – and yet individuals who suffer from obesity are repeatedly made to feel shame that they are not “normal”. The rationale appears to be that shame will incentivise the person with obesity to lose weight and “get healthy”. Studies suggest the opposite is true. Fat people are already ashamed, and have lower self-esteem and a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety than people with “normal” BMIs. Feeling stigmatised increases the production of stress hormones that damage health, and triggers “obesogenic processes” – in other words, the tendency to go home from the doctor’s surgery and open a bottle of wine or a bar of chocolate and ruminate futilely about what a worthless person you are.

Not me. My knee’s better, I’m on a diet and have lost 7kg. But if you think I’m going to try and fit into those size 6 jeans I wore when I was 15, you have another think coming.

[1] Quetelet’s exploration of the norm and the normal was a new concept in its day, and his obsession with it went well beyond pure science. He declared: “If the average man were completely determined, we might consider him as a type of perfection; and everything differing from his proportions or condition would constitute deformity or disease; everything found dissimilar, not only as regarded proportion and form, but as exceeding the observed limits, would constitute a monstrosity.” https://www.maa.org/sites/default/files/images/upload_library/22/Allendoerfer/stahl96.pdf

[2] These days, the crude weight-over-height-squared ratio even falls down with the white Western males on which it was originally based: for tall people, height and girth do not increase in the same proportion proposed by Quetelet, and the BMI of tall people is thus likely to be particularly useless. Populations have changed a lot since 1832. Better diets and less punishing lifestyles have tended to fill people out.

[3] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0048448

[4] For three years the doctors of Rachel Hiles, 20, insisted that her shortness of breath would improve if she ate less – until they realised she needed emergency surgery for lung cancer. Luckily, Hiles survived – minus a lung. Her case is not an outlier.

[5] In one of his better gags, the prime minister continued: “And I have since lost 26lb, and you can imagine that in bags of sugar. And I am going to continue that diet, because you have to search for the hero inside yourself in the hope that individual is considerably slimmer.”

[6] 200,000 Britons have appetite gene that adds two stone | News | The Times