A sideways look at economics

A friend recently emailed me a link to a golf trolley advertised online. A golf trolley with a difference: in addition to the standard slot for the clubs and scorecard was space reserved for a baby! Apparently, the availability of this single product is key to my mate’s new-found willingness to become a ‘stay-at-home dad’. “Yet another example of new gadgets driving able-bodied folk out of the workforce”, I replied.

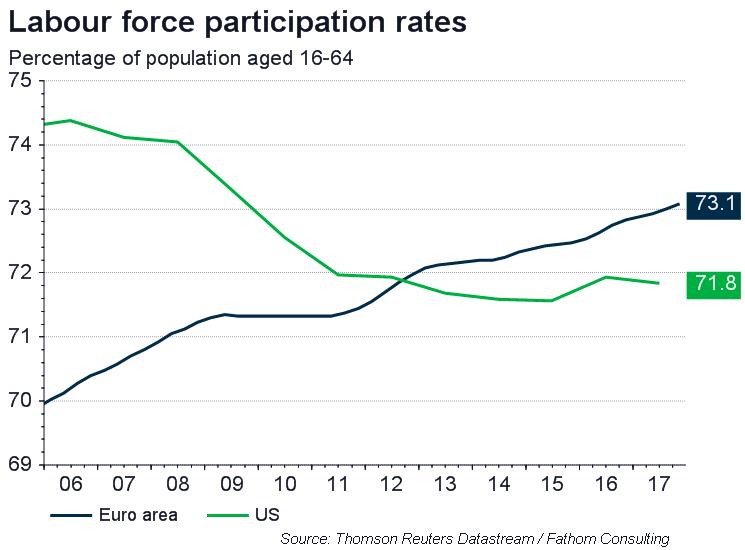

On a more serious note, since the crisis we’ve seen a continuation of the secular decline of the percentage of the working-age population[1] that’s either in work, or looking for work, in the United States. This has been particularly evident for male workers, whose participation has fallen by 7 percentage points over the last two decades. Meanwhile, the percentage of the total working-age population in the labour force has declined by 4 percentage points. These statistics, known as participation rates, are an essential element of an economy’s productive capacity.

Meanwhile in Europe, the opposite trend is evident: working-age workforce participation is currently at its highest ever level in the euro area. While the US and euro area economies have their differences (as guests at our recent Monetary Policy Forum event will be aware), they are also subject to many common influences. Will more Europeans in this age group continue to join the workforce or will the US trend just arrive later in the euro area, like bad coffee? To answer that question, we need to look at the drivers of working-age participation rates.

Technology is changing the nature of employment and the skill set that’s demanded, with not just routine but also medium-skilled tasks now being automised. As far back as 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that technological progress would deliver 15-hour weeks and an abundance of leisure time for us all. Of course, what we’ve seen in practice has been somewhat different: some are working longer hours than ever before, others none at all. The rewards to labour (i.e. wages) are thus increasingly concentrated, with those who have abundant leisure not necessarily equipped with the resources to enjoy it. Furthermore, research[2] demonstrates that there are social benefits to participating in the workforce that can’t be retained through wealth redistribution. To protect participation rates and the related social externalities, education systems will need to deliver more of those who can support technological progress, rather than be replaced by it. On this count, although total enrolment in tertiary education is higher in the US, the proportion of graduates in STEM subjects is higher in the euro area. The expected increase in demand for STEM graduates over the coming decade is amongst the highest of any discipline, in both the US and the EU.

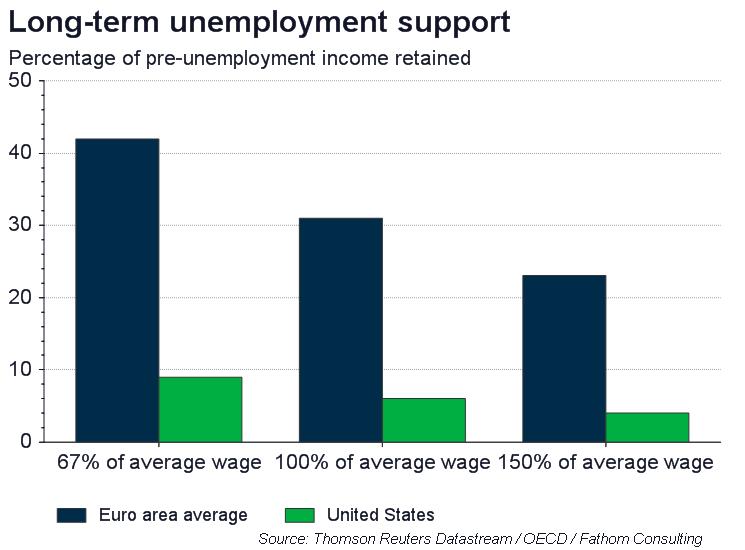

If technology is affecting the demand for labour, are state welfare systems damaging the supply by reducing the incentive to work? Dependence on social benefits in ‘welfare states’ is frequently referenced by those on the right-hand side of the political spectrum as representing a negative supply-side distortion. The chart below shows the proportion of income that’s retained by a single individual in different pay brackets after heading into long-term unemployment in the US and the euro area. As expected, the average unemployment support in the euro area is considerably higher. Recalling that those characterised as ‘unemployed’ must be actively looking for work, is it possible that higher benefits are actually keeping people economically active and in the job market, as opposed to giving up entirely and disappearing from the labour force? The percentage of men in the US who aren’t in the labour force but want a job (i.e. no longer looking for a job despite wanting one), is currently at its highest level since the mid-1990s.

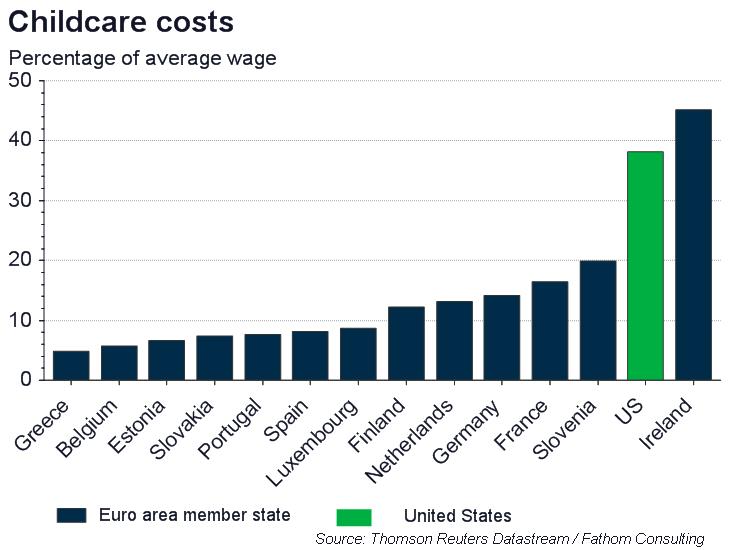

A significant part of the rise in workforce participation in Europe is due to increased female participation. Indeed, the European Commission is explicitly targeting female participation as a means by which to achieve its 75% participation rate (20-64 age group) target by 2020. A range of specific factors influence the willingness and capacity of women to join and remain part of the workforce, many of which relate to deep-rooted gender roles. These include the cost and quality of childcare services and the gender pay gap. The US lags behind all but one euro area country on both of these metrics.

It’s not easy to determine the drivers of workforce participation, and there are other factors at play in the US, such as outsized incarceration rates and demographic changes,[3] that aren’t covered by this blog post. Indeed, in terms of the contribution of labour to the economy, other measures of labour utilisation (such as the average number of hours worked) are arguably equally as important as participation rates.

If we just look at the latter though, it seems that some of the factors apparently driving down workforce participation in the US are absent, or are at least better mitigated, in Europe. Consequently, there are reasons to hope that the euro area’s participation rate will remain at its elevated level, and not track the secular decline of its US counterpart. Undoubtedly, both economies will need to equip their workforces with the skills needed to complement technological progress and, where this isn’t possible, to ensure reasonable distribution of increased profitability. From a personal perspective though, the main risk to my continued participation is the availability of those golf trolleys.

[1] The focus is restricted to the working-age population to reduce the impact of demographic changes, such as an ageing population.

[2] Michael Dotsey, Fujita Shigeru and Leena Rudanko, ‘Where is everybody? The Shrinking Labour Force Participation’, Economic Insights, 2.4 (2017).

[3] Even the working age (16-64) participation rate is influenced by demographic changes — while some of the ‘baby boom’ generation have yet to reach the official retirement age, the likelihood of still being part of the workforce decreases with age and hence the ageing of this outsized generation has reduced participation rates.