A sideways look at economics

It seems fitting that the NHS, which celebrates its 70th anniversary in July, should be the subject of one of the first TFiFs of the New Year. It is, after all, a time when many of us commit to year-long goals, the vast majority of which, it seems, relate to health and wellbeing. The bacon is banished, and quinoa and pulses fill the trolley in a bid to finally undo years of overindulgence and gluttony.

Just over half of us at Fathom have made New Year’s resolutions, and all of them relate to our health. “Drink less alcohol” and “exercise more” appear to be common goals. The lure of the ‘golden arches’ will prove too much for many, with 92% of health-related resolutions typically abandoned over the course of a year. Nevertheless, all but one member of the team is still going strong.

That member, I’m ashamed to confess, is me! After jumping on the ‘Dry January’ bandwagon, and readying myself for an assault course of peer pressure and criticism, I failed at the first hurdle. The admin of the ‘Dry Jan’ group even highlighted the perils of announcing such ambitions, warning “don’t remind everyone about it all the time, they start to resent you.”

He was right. It became my friend’s sole aim to get me to have a drink!

My blip aside, it would seem that we’re a fairly healthy bunch. We’ve even taken steps to address our ‘cake culture’, substituting Monday morning pastries for fruit. But dig a little deeper, and we don’t fare quite so well. Undeterred by the steepening taxes and advertising bans, a quarter of us smoke. That is more than the UK average, at 15.8% of the adult population. Nevertheless, national evidence suggests that such disincentives do work, with even those that still smoke, smoking less.

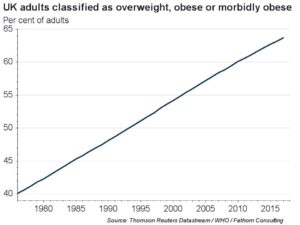

So why shouldn’t it work on fatty foods? According to the Office for National Statistics’ Health Survey for England, published last month, just over 60% of those aged 16 and over are overweight, with nearly half of those registering as obese. That makes us the fat cats of Europe, surpassed by only Turkey and Malta’s expanding waistlines.

Struggling to meet burgeoning demand, the NHS has been tightening its belt, while we have been loosening our own. A survey coordinated by researchers at the University of Cambridge found that obesity is now second only to smoking as a cause of premature death in Europe, with the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer all increasing.

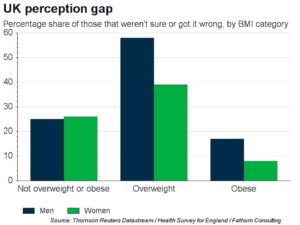

Just one more chocolate won’t make that much difference, right? Problematically, 43% of the adults deemed medically overweight by the Health Survey for England believed that they were “about the right weight” when questioned. As our chart highlights, that perception-reality gap was larger for men than women, with 58% underestimating or unsure of the problem, versus just 39% of women. Women were also more likely to be “trying to lose weight”, even though a higher proportion of men surveyed were overweight or obese.

This isn’t just a case of favourable self-perception. When asked what they thought Santa’s net calorie intake during his Christmas delivery round would be, Fathom employees, who pride themselves on their analytical skills, grossly underestimated the calorie content of a mince pie and Christmas tipple, while severely overestimating the amount burnt during the delivery round.¹ Those of us with a truly analytical brain know that it’s Rudolph and his pals that do the heavy lifting!

Recognising that there isn’t much fat left to trim from the NHS, and in order to improve public health and awareness, there’s a growing consensus that obesity needs to be tackled. One idea, as the NHS limps into its 70th year, is a ‘fat tax’. The aim is to make unhealthy foods cost more, and steer people towards healthier alternatives. But having discussed this with friends and family over the past week, I’ve been surprised by the degree of resistance. One colleague, who wishes to remain anonymous, said, “what about my freedom of choice? It’s my right to be fat.”

But is it?

According to the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence, around £16 billion a year is spent either directly or indirectly on costs related to obesity, and that figure is rising. Those costs are imposed not only on those who are obese, but on the rest of society. Recognising that nagging the nation was falling short, in his March 2016 Budget Statement George Osborne announced a tiered levy on sugar-sweetened soft drinks. Needless to say, it attracted much criticism from the drinks industry and members of the public aggravated by the idea of a ‘nanny state’.

Nevertheless, it appears to be working. Soft drinks manufacturers have reduced the sugar content by 10% since 2015 in anticipation of the levy which comes into force in April — arguably an easy task when one can contains up to 20 teaspoons of sugar. Some of the biggest culprits are energy drinks, with Waitrose banning sales to under-16s last week.

A hospital in Manchester has also acted, removing added sugar, sugary snacks and fizzy drinks from its canteen menu, making it the first to do so. But eating healthier food is more expensive. And since food represents a greater proportion of total spending in poorer households, the burden of a ‘fat tax’ risks falling disproportionately on them. No wonder policymakers are wary!

One solution would be to use the ‘fat tax’ revenue to subsidise fruit and veg, increasing the relative price differential and with it the sensitivity of demand, helping to neutralise the pinch. An experiment which saw the price of low-fat snacks fall relative to regular alternatives in a vending machine had the desired effect. Sales of healthy snacks as a proportion of total sales rose from 25.7% to 45.8%, falling back again when prices were returned to normal.

But other, more comprehensive, studies paint a more mixed picture. And Denmark, the first country in the world to impose a tariff on saturated fats, quickly back-pedalled, abolishing the tax a little more than a year after it was implemented. The reason: it caused a bureaucratic nightmare; encouraged cross-border trading; and put Danish jobs at risk.

Ultimately, while such a scheme may increase the consumption of fruit and veg, bringing it in line with dietary recommendations, it seems a suite of interventions will be needed in order to materially change the risks of disease and the burden on the NHS. In other words, old habits die hard. And speaking of which, beer o’clock beckons.

1.However you slice or dice it, after delivering presents around the world and consuming multiple mince pies, his net calorie intake would be in the billions. Over a quarter of Fathom employees predicted 5000 calories or fewer. One member of staff didn’t even know what a calorie was. Their defence: it’s likely that many of the mince pies left out for Santa are really consumed by mum or dad. And in some families it’s traditional for Santa to take no more than a single bite of the mince pie. It’s possible he reaches his limit after a few thousand calories, and what remains is quietly snaffled by the parents.