A sideways look at economics

In Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan, Lord Darlington declares that a cynic is “someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.” As far as some of my friends are concerned, this epithet might apply equally well to an economist. Clearly, these individuals have not met Erik Brynjolfsson, Felix Eggers and Avinash Gannamaneni. This trio of economists has spent a considerable amount of time — and money — trying to measure the value of something that has a price of zero.[1] I speak, specifically, of those digital goods and services that are available for free. Their results are staggering.

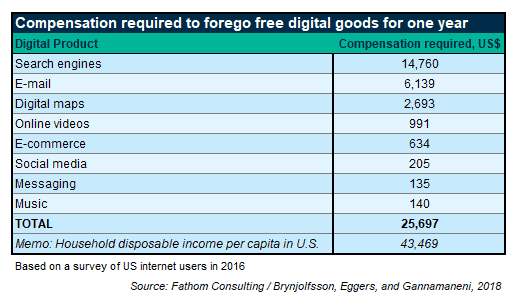

The typical US internet user would, it transpires, require compensation to the tune of $25,697 in order to forego access to these products, ranging from search engines through to social media, for just one year. To my mind, that is a phenomenal amount of money. Indeed, it is more than 50% of US household disposable income per capita. Can this really be right? In an effort to find out, I conducted a quick straw poll among my colleagues here at Fathom.

Rather than ask participants to value the entire range of ‘zero-marginal-cost’ products available on the internet — that would take time, and time is money — I requested instead that they name the free smartphone app that they valued the most, and then state what sum of money they would require in order to forego access to that app for one year. Figures quoted were comparable to those discovered by Brynjolfsson, Eggers and Gannamaneni. The two most popular apps, by some margin, were WhatsApp and Google Maps, with annual valuations ranging from as little as £40 to as much as £5,000. As an afterthought, one respondent, who required £200 to part with her favourite app for a year, added “although, of course, I wouldn’t be willing to pay that much for the app”. This simple observation tells us much about the cause of those sky-high valuations. It’s all to do with the way that the question is framed.

Unfortunately, people do not always behave in quite the way that many economists imagine they do. One of the first researchers to observe this was the US-Israeli psychologist Daniel Kahneman. Writing with Amos Tversky in 1984 he observed that, when asked to value a good or a service, the answer that people gave varied hugely according to the way in which the question was framed.[2] Specifically, he found that people suffered what he calls ‘loss aversion’. Ask a person how much they’d require to part with something they already possess, and they’ll typically quote a much higher price than if instead you ask them how much they’d be willing to pay to receive something they don’t. Valuations, it would appear, differ not just between people but within people.

Daniel Kahneman’s work poses a challenge to many long-established principles of economics. One of these is the Coase Theorem. Associated with the work of the British economist Ronald Coase, the Coase Theorem states that a well-defined system of property rights can be sufficient to overcome the problem of externalities.[3] Take pollution as an example. As long as it is clear whether it is the polluter who has the right to pollute, and the neighbour who must incentivise him to pollute less, or whether it is the neighbour who has the right to clean air, and the polluter who must incentivise her to accept more pollution, a process of bargaining between the two parties will lead to precisely the same outcome. But this cannot be the case if valuations vary in the way predicted by Daniel Kahneman.

People are complex creatures. They don’t behave in ways predicted by economic textbooks of old. I found the notion that US internet users were willing to pay more than half their annual disposable income to enjoy the likes of Google Search, Facebook and Spotify quite literally incredible. As it turns out, because of loss aversion, they almost certainly weren’t willing to pay that much![4] Both Ronald Coase and Daniel Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for their work. Ronald Coase got his in 1991, and Daniel Kahneman in 2002. So perhaps it can at least be said that the discipline is moving in the right direction.

[1] Erik Brynjolfsson, Felix Eggers,and Avinash Gannamaneni, ‘Using Massive Online Choice Experiments to Measure Changes in Well-being’, NBER Working Paper No. 24514 (2018).

[2] Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, ‘Choices, values and frames’, American Psychologist, Vol. 39, No. 4 (1984), pp 341-350.

[3] See for example Ronald Coase, ‘The problem of social cost’, The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 3 (1960), pp 1-44.

[4] For the sake of argument, even if loss aversion meant that the ‘willingness to pay’ valuation of free internet services was just one half the ‘compensation required’ valuation, the consumer surplus would still be vast. The nature of competition in the industry, and the fact that suppliers face a near-zero marginal cost, prevents this consumer surplus from being eroded.