A sideways look at economics

Three weeks ago, I finished my studies and returned to hallowed halls of Fathom Towers, virtually at least, working on our Financial Vulnerability Indicator (FVI). While I would love to bore you all with the riveting decisions involved in building the FVI, most of you wouldn’t read past the first paragraph. So instead, I’ll use it as a neat hook to talk about something you’ll be far more interested in: the evolution of policy and why it matters now.

For those who don’t know much about our FVI, and I’m reliably informed that you people do actually exist, it assesses the risk of sovereign, banking and currency crises. In a former life, the FVI resided in Excel, but has now been gloriously recast in the medium of the R programming language. Over the course of the next month, my esteemed colleague Toby will be handing his role in the project over to me.

To anyone who has taken responsibility for code written by someone else, the challenges are obvious. No matter how well written the code, and in this case, of course, Team FVI has excelled itself, there will be times when it’s not clear why a piece of code has been included. So, do you follow your instincts and remove the code? Perhaps, but the paradox of Chesterton’s Fence would suggest you should think twice.

This paradox was explained by G.K. Chesterton in his 1929 book The Thing as follows:

“There exists a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

The analogue to maintaining code is clear: if you don’t know why someone put this code here, you’re taking a risk by removing it. While the consequences of changing a line in code can be catastrophic, it can often be traced back to the missing code and corrected. Chesterton’s Fence can be more pernicious when the effects are slower moving and therefore less obvious. A clear case of this was the repeal of the Glass-Steagall act in 1999.

During the Great Depression, consumers lost confidence in the ability of banks to repay their deposits with cash. This led hordes of anxious deposit holders to demand immediate repayment of their deposits causing many banks to fail. The Glass-Steagall act created a clear separation between commercial banks and other financial institutions, created the federal deposit insurance and importantly made clear distinctions about what banks could and could not do.

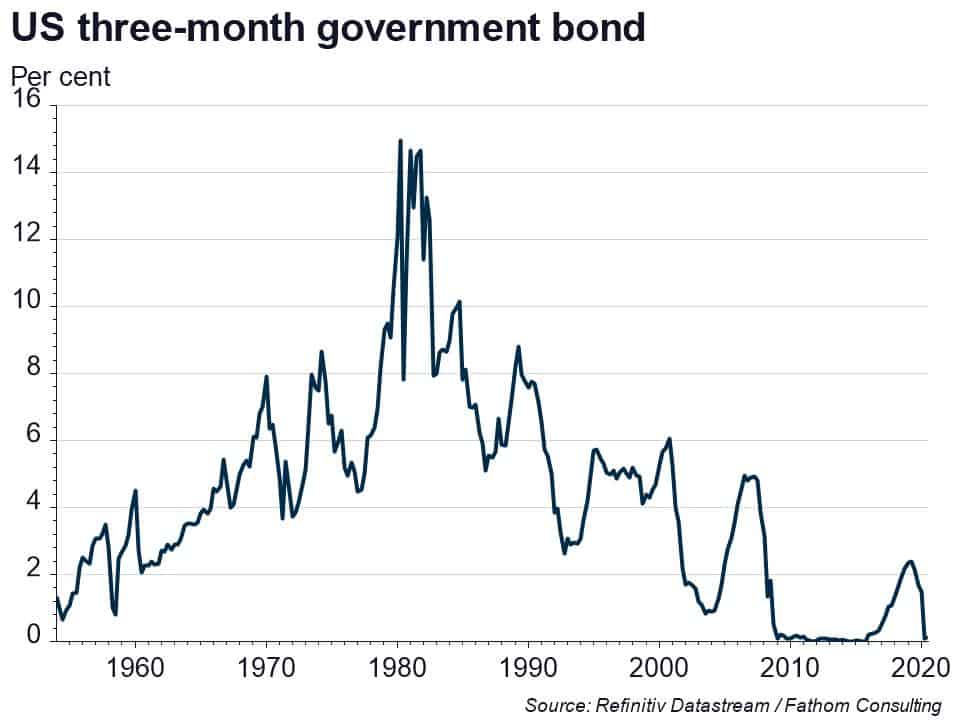

However, the act was not perfect. It included Regulation Q which prevented banks from paying any interest on deposits, probably after lobbying by special interest groups wanting to improve profits in the banking sector. As a member of the generation that hasn’t earned more than 0.5% on an instant access deposit account, it’s hard to see what the big deal is all about. But apparently this was a big deal. As Robert Lucas noted, Regulation Q was a relatively slack constraint when interest rates were low in the first 20 years of its existence. But, as interest rates began to rise in the late 1970s, the wedge between deposit rates and risk-free interest rates bloated, as did the monopoly profits accruing to the banking sector.

This encouraged new entrants and innovation in the sector resulting in various feats of financial engineering — such as eurodollars and ‘sweeps’ — allowing individuals with instant access deposits to earn interest without violating the Glass-Steagall act. And by the time 1999 came around, such was the extent of activities circumventing Regulation Q, the removal of the Glass-Steagall act was little more than a formality.

However, this largely neglected the fact that Regulation Q was not the central tenet of the act, but instead an addition. The central tenet of the act was action to reduce the risk of bank runs. After 66 years of the Glass-Steagall act, during which the US did not experience a single financial crisis, it experienced the largest crisis since the Great Depression with echoes of the same causal mechanism. The difference: rather than a shortage of liquidity caused by the unwillingness of households to lend to banks (via deposits), we saw a shortage of liquidity because banks were unwilling to lend to one another.

To be clear, repealing the Glass-Steagall act is unlikely to have ‘caused’ the financial crisis. By the time it was repealed, the constraints it had imposed were largely circumvented by the above-mentioned financial innovations. But the lack of action in updating the regulation to fit the changing nature of banking may well have contributed.

The repeal of Glass-Steagall in many senses is a striking display of the paradox of Chesterton’s Fence. It was repealed without dealing with the underlying vulnerability it was designed to prevent. However, it also illustrates an issue that the paradox doesn’t account for well: society evolves and therefore its regulations must evolve with it.

This conflict between reformers and obstructors tends to lead to a situation where radical changes are only made when crisis reduces the decision set such that avoiding making a decision, the general preferred decision of mankind, is no longer a decision. This idea is encapsulated by Milton Friedman in the 1982 preface to his signature treatise Capitalism and Freedom:

“Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.”

At this point in time, we find ourselves in such a moment. With the outbreak of coronavirus, governments in the developed world have disregarded the post-financial-crisis doctrines of austere fiscal policy and supported their residents in an unprecedented way. But the confidence of developed world governments in taking on such large amounts of debt and such large fiscal deficits has not occurred in a vacuum. Rather, these ideas have long been discussed by economists, including those at Fathom.

A foundation for these ideas was in the criticism of the response to the financial crisis. Much of the post-financial-crisis analysis centred around the idea of ‘debt dynamics’. This idea is encapsulated by the simple debt dynamics equation:

dt+1 ≈ (1 + r – g)dt – st+1

Where dt is debt-to-GDP in time t, r is the average interest rate on government debt, g is the growth rate of GDP and st+1 is the primary fiscal surplus in time period t+1. In simple terms, the equation argues that if an economy runs too large a fiscal deficit, debt will be on an explosive path.[1]

Unfortunately, this logic to a large extent informed the decision of governments in the wake of the financial crisis. It is unfortunate because it neglects the endogenous nature of the variables in the model by treating a government balance sheet like a household balance sheet. Specifically, it ignores the strong relationship between government spending and GDP. This is especially true, as Valerie Ramey notes, in times when monetary policy is stuck at its lower bound.

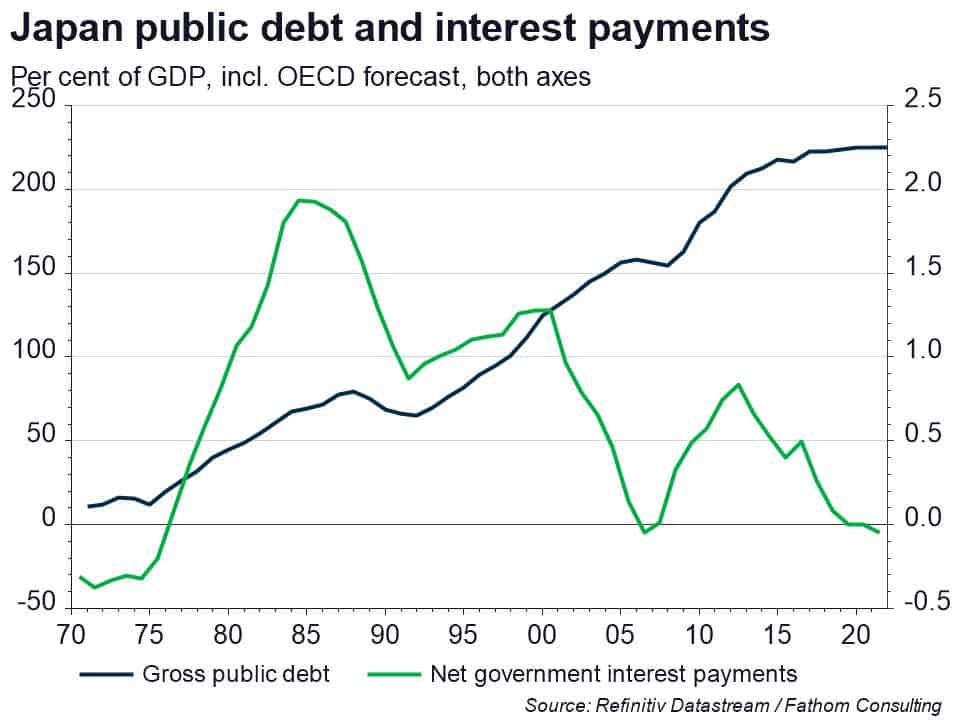

Whilst some governments around the world have sustained high levels of debt, for example Japan’s government debt is currently around 225% of GDP, it is still not completely clear where the limit is for most countries. The main risk surrounding these high levels of debt, for developed economies that print their own currency, is shifts in market expectations about the sustainability of the debt pile. Fathom recently argued that high levels of debt are likely to cause hyperinflation whenever markets believe that policymakers would rather tolerate hyperinflation than use real resources to repay their debt. Where responsibility for the creation of currency and reserves is delegated to an independent central bank, the risk of this is to some extent mitigated, conditional on the credibility of the central bank’s independence.

We shall return to the question of debt sustainability in light of COVID-19 in our next quarterly forecast, due to be finalised in early September.

While many developed world governments have previously been hesitant to build up anywhere close to Japan’s level of debt, COVID-19 has forced their hands. The increased level of government debt, and increased acceptance it will gain simply by virtue of having been implemented, could have far-reaching consequences by bringing fiscally costly policies closer to the mainstream. In particular, policies such as universal basic income and policies to deal with issues like climate change mitigation and adaptation and demographic change will require a large contribution from the exchequer. That would in turn require higher taxes or larger deficits and debt piles.

I, for one, can’t wait for the raft of universal basic incomers making organic grass-fed ghee from their log huts in the Scottish Highlands. But until then, I’ll have to settle for half price Nando’s on Rishi.

[1] This only occurs where r > g. If r < g debt will always converge to a finite level in this model.