A sideways look at economics

Today, 10 September 2021, marks 20 years since one of the great scandals of British television began to unfold. Charles Ingram, a former British army major, was a contestant in the hot seat of the quiz show ‘Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?’. At the end of the first day’s filming the major’s chances did not look particularly promising, as he had already used two of his lifelines on early questions. But by the time cameras stopped rolling on 10 September 2001, Ingram had won the million-pound jackpot.

The celebrations never really got started, however, as the major was accused of cheating. The recording was never broadcast, and Ingram’s winnings were withheld by the show’s organisers Celador while an investigation began. Ingram was accused of being aided by his wife in the audience and by one of the other contestants on the sidelines, who gave a cough each time the correct answer was read out by the host Chris Tarrant, letting Ingram know which of the four possible answers to choose.

The UK version of ‘Who Wants to Be a Millionaire’ had not seen drama like it. After the intense attention, the show’s fortunes eventually went into decline. The quiz was canned at the end of its 30th series in 2014 amid drifting ratings, before returning in 2018 with a new host, Jeremy Clarkson. Despite its fluctuating fortunes, one thing about the show has remained consistent throughout: the one million pound jackpot that so tempted Ingram and his confederates.

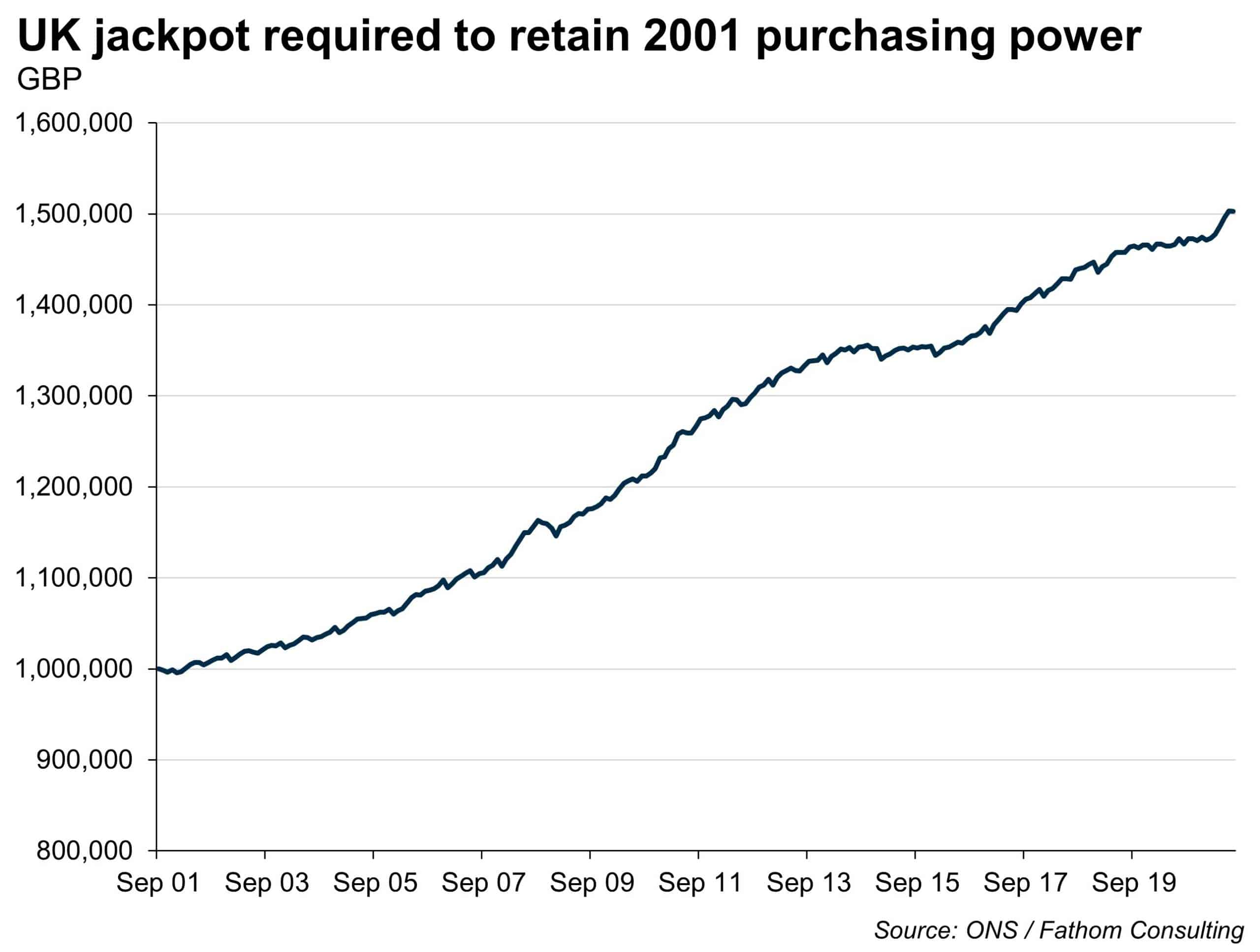

But how tempting does that prize look today? Because of inflation, the purchasing power of the jackpot has decreased, making it increasingly cheaper for the organisers to pay out prizes over time. A British contestant winning the jackpot today would need to receive a prize of around £1.5 million in order to gain the same purchasing power as Ingram, if he had been allowed to keep his winnings back in September 2001.

The show’s producers probably do not want to change its iconic name or break the link between the name and the top prize. However, they did make a concession of sorts to inflation, from 2007 reducing the number of correct answers required to win the top prize from 15 to 12 to make the quiz easier — though this format of the show did not yield any jackpot winners. Since the 2018 reboot, they have reverted to the original 15 question format, though the producers did add a fourth lifeline to ‘ask the host’, in which the contestant relies on the questionable general knowledge of new host Clarkson.

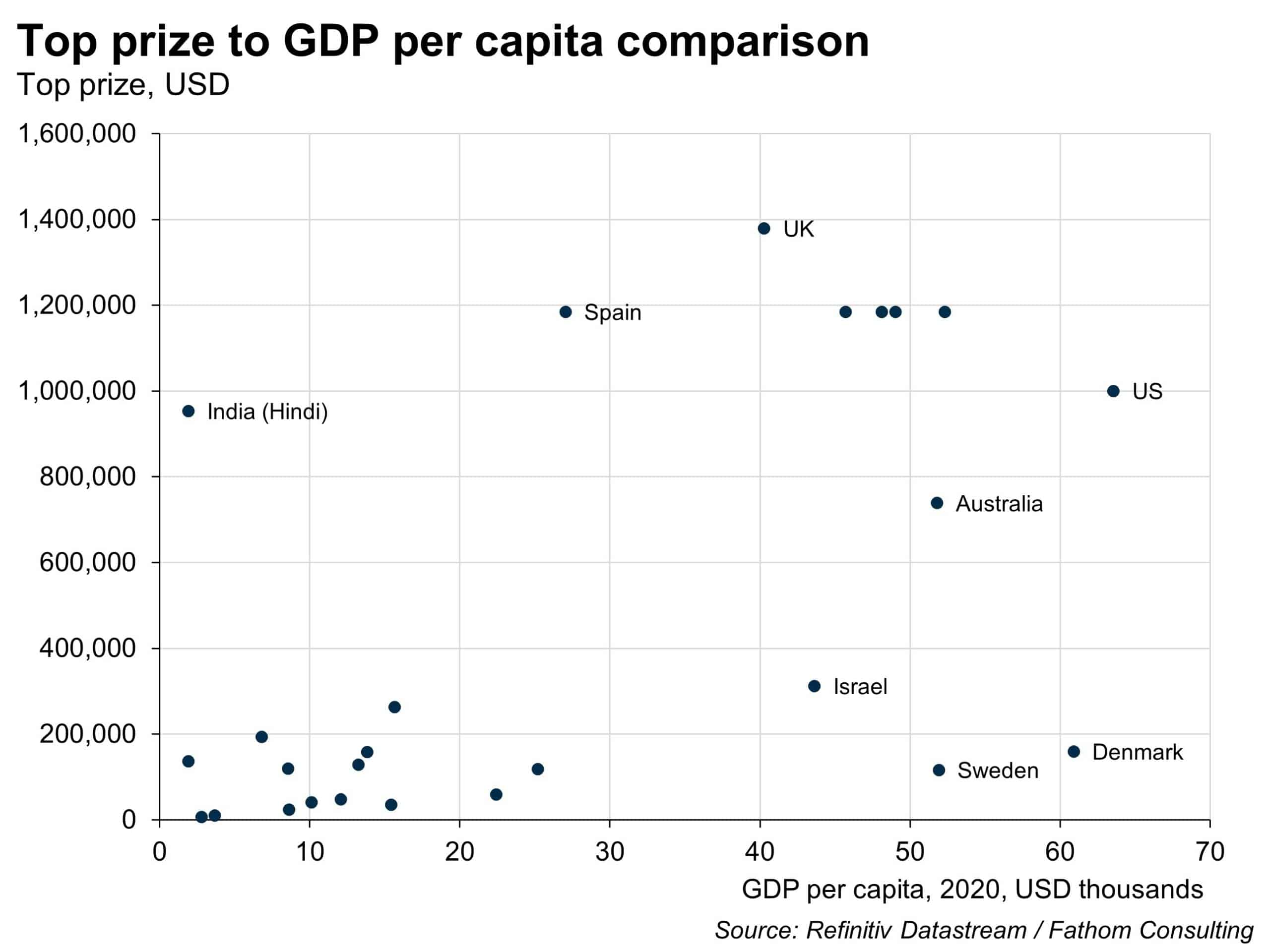

But if the UK winnings have become less generous, it’s worth noting that the US version of the show is even stingier. Not only are ‘million’ winnings denominated in dollars, not pounds, but prizes (unlike the British show) are tax deductible; and anyone who wins either the half a million dollar second prize or the one million dollar top prize are paid just $250,000 as an initial lump sum, and the remainder in annuities over time.

Despite this, the US version is far from the least generous of all the international versions of the show. Considering per capita income, Denmark and Sweden stand out as offering a poor return for winning the top prize. Both countries have weak currencies in absolute terms, making one million Danish krone or Swedish krona a poor return in an international comparison. On the other hand, India’s Hindi version of the show offers a very generous prize relative to GDP per capita.

In 2010 the US show made the same style of inflation adjustment to the format as the UK did between 2007 and 2014, reducing the number of questions required to win the top prize to 14. So perhaps the UK version should once again follow suit? Or perhaps it should now be renamed ‘Who Wants to Be a Million-and-a-half-aire?’. It is a catchy enough title to get you to read this TFiF.